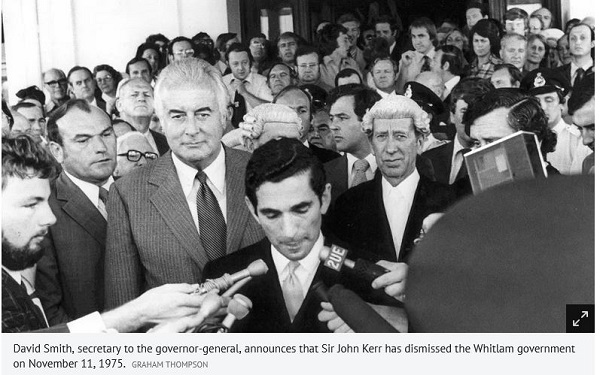

The Whitlam years were certainly tempestuous years. There is a tendency, even by acolyte’s, to think that the economic turmoil of those years was made in Australia, by EGW, his treasurers and his ministers.

Who can forget the Khemlani loans affair, where Minister for Minerals and Energy, Rex Connor, was seeking to borrow US$4 billion, a lot of loot for the time, for resources projects without going through Treasury. My understanding is that the scheme was hatched by Connor, Whitlam and a small kitchen cabinet, perhaps including Lionel Murphy. After it became public and Cabinet put the kybosh on the scheme, Connor was still found to be liaising with the shadowy Tirath Khemlani. Whitlam dismissed Connor.

Khemlani, it is said, never made a loan in his life, and perhaps had contacts with the CIA.

Cairns was dismissed a few months later over a separate loans affair, where he (as claimed) unknowingly signed a letter and misled parliament by saying he hadn’t.

For these and other reasons, the Whitlam government at times looked highly shambolic.

Yet economic turmoil was not confined to Australia. That first Khemlani link reminds us that the price of oil quadrupled between 1973 and 1974. That’s why the Middle East was awash with petro dollars and a Khemlani figure could exist. Ian Verrender, the ABC’s busianess editor, now invites us to think again.

Verrender riffs off a piece in the AFR by John Stone, former treasury secretary and National Party senator, plus “outspoken critic of multiculturalism and a supporter of the Samuel Griffith Society, which he helped found”. Stone was also at one time John Howard’s finance spokesman in opposition. In his piece The economic policy madness of the Whitlam era Stone outlines a tale of woe. But:

As Stone rightly points out, Australia did not go into recession. What he fails to mention is that America did. So did the UK. And they were no ordinary recessions.

Both our northern hemisphere allies endured long and painful slumps, the chaotic fallout from which reverberated through the global economy, including Australia.

Not only that, inflation ran wild in both the northern hemisphere economic superpowers and throughout the developed world. It was a global recession that marked the dramatic end of the post-war boom.

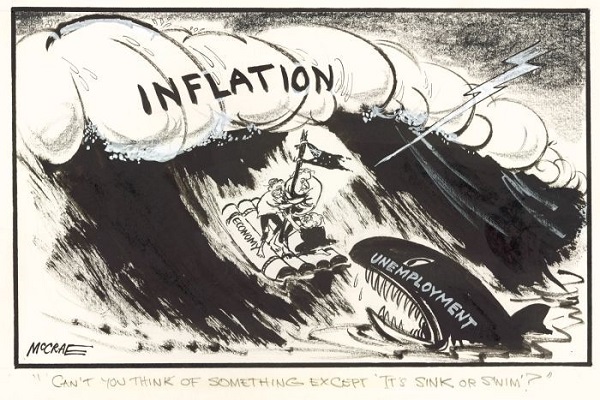

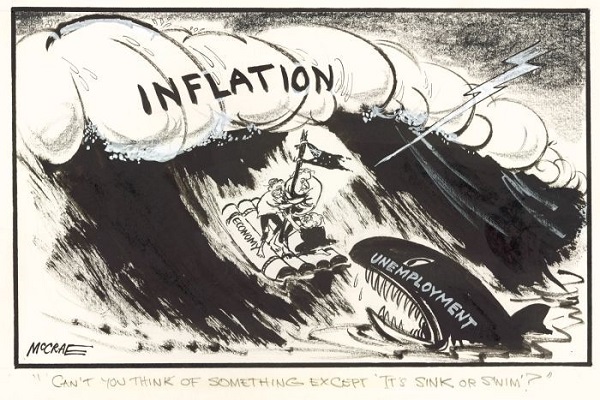

This was the time of rampant stagflation, a rare phenomenon in economics where inflation and unemployment rise simultaneously. It’s a nightmare scenario for policymakers. Raise rates to dampen inflation and you exacerbate unemployment. Try to fix the jobs crisis and you fuel inflation.

There were a number of factors behind the global recession.

The Bretton-Woods financial system – instituted after the war that tied the US dollar to the price of gold – collapsed in the early ’70s, itself enough to engineer a significant slump in global activity. This followed attacks on the currency as the US ran up a constant series of balance of payments deficits.

The sudden collapse of the system and the immediate devaluation of the US dollar, which from then on became a fiat currency valued against other currencies, created havoc on trade and current account balances throughout the developed world.

Add to this that the Arab world had formed the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries and in 1973 deliberately squeezed supplies.

The price of oil quadrupled between October 1973 and the following January. That’s correct, energy prices rose 400 per cent in four months, sending shockwaves through developed world economies, underscoring the dramatic price rises that, in turn, fed through to wage demands.

Between 1973 and 1975, the Whitlam era, inflation in the UK grew from 7.4 per cent to 24.89 per cent – vastly higher than anything experienced in Australia.

Great Britain was wracked by industrial disputes. Miners walked off the job, coal supplies dwindled. So dire was the energy situation, UK prime minister Edward Heath instituted the three day week as commercial electricity users were restricted. Food queues formed.

America, meanwhile, endured its worst recession since the Great Depression between November 1973 and March 1975. While the unemployment spike was relatively short-lived inflation soared from a relatively modest 3.65 per cent in early 1973 to a 12.34 per cent peak at the end of 1974 before tapering off during 1975.

Certainly under Jim Cairns stewardship the money flowed. Verrender says:

Gough Whitlam’s first two treasurers, Frank Crean and Jim Cairns, were widely criticised for their performances. Cairns, especially, appeared to be distracted by assets of another kind, and spending during his reign blew out spectacularly.

But Bill Hayden’s budget, delivered shortly before The Dismissal, had many in the Opposition worried. It was a responsible document designed to bring inflation and unemployment under control.

Personally I had a couple of long conversations with Bill Hayden when he was Treasurer and was impressed. The Whitlam Government had a further 18 months to run and things may have settled down.

It should be remembered that Malcolm Fraser only had the capacity to block supply courtesy of highly unorthodox senate replacements. First, in March 1975 the independent Cleaver Bunton was appointed by NSW Premier Tom Lewis to replace Lional Murphy who Whitlam had appointed to the High Court. Secondly Albert Patrick (Pat) Field was appointed by Queensland under Joh Bjelke-Petersen following the death on 30 June of Queensland ALP Senator Bert Milliner. Field had been an ALP member, but offered himself, promising never to support Gough Whitlam.

These were highly improper and undemocratic acts that were accepted by Malcolm Fraser.

Back to the economy, it could be that Cairns’ profligacy acted like a massive Keynesian stimulus package, saving Australia from recession.

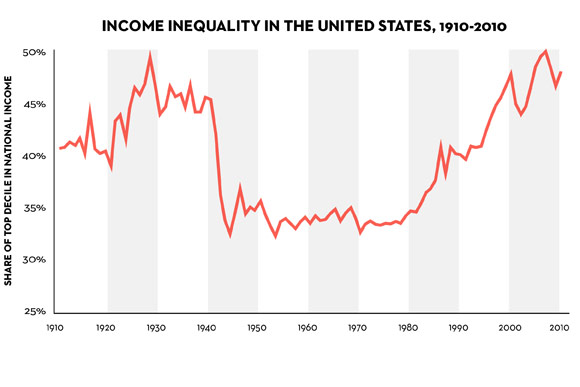

More generally, figures like Immanuel Wallerstein see capitalism in its main centres doing it tough from the early 1970s. Capitalists sought to maintain their profits by beating down wages, by outsourcing, by financialisation, including increasing privatisation of human activities and experience. It’s well-known that American workers struggled to maintain real wages from the 1970s onwards. The modern manifestation of neoliberalism seems to date from about this time.

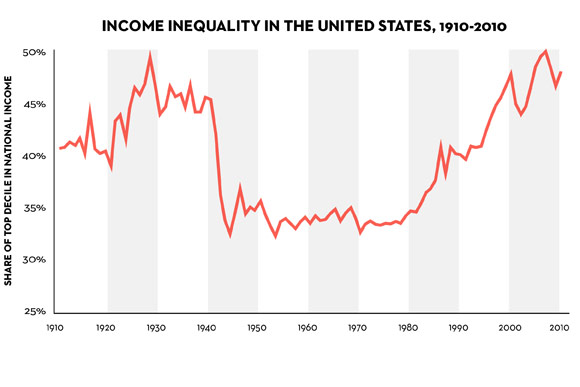

Thomas Piketty’s work on inequality is startling. This graph shows the rise in inequality in the US by charting the top decile’s share of income:

The 2012 data, too late for inclusion in the book, sees a new high of over 50%.

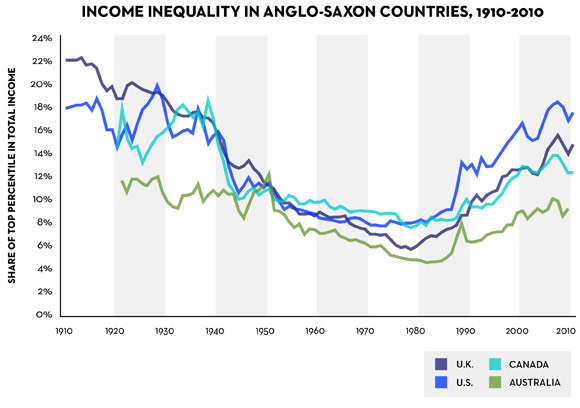

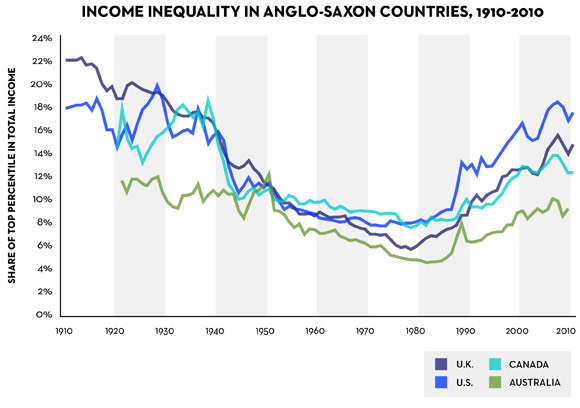

There’s a similar pattern if you look at the top 1% in the Anglo-Saxon economies:

Clearly something broader and deeper is going on that Whitlam’s whole program of social investment perhaps helped to protect us from. Certainly as Verrender says, Stone “still fails to grasp the impact the global economic upheaval had on Australia.”