Damian Carrington at The Guardian:

-

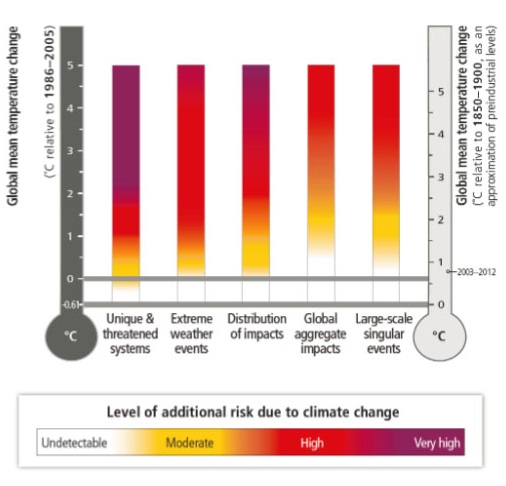

Climate change is set to inflict “severe, widespread, and irreversible impacts” on people and the natural world unless carbon emissions are cut sharply and rapidly, according to the most important assessment of global warming yet published.

The stark report states that climate change has already increased the risk of severe heatwaves and other extreme weather and warns of worse to come, including food shortages and violent conflicts. But it also found that ways to avoid dangerous global warming are both available and affordable.

“Science has spoken. There is no ambiguity in the message,” said the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon…

(Emphasis added)The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) is found here.

Roger Jones at The Conversation:

- acting on climate is ultimately an ethical, not an economic, consideration. Insufficient policy action is a declaration of self-interest, condemning our children, grandchildren and the planetary system that supports them, to a dystopian future. That’s what the report should say.

Ban Ki-moon:

- “Leaders must act. Time is not on our side.” He said that quick, decisive action would build a better and sustainable future, while inaction would be costly.

Tony (‘coal is good for humanity’) Abbott still refuses to address climate change at the G20 meeting as it would distract from discussion on growth. Nicholas Stern says climate change is core business if you’re concerned about growth:

- The G20 is the most effective forum for the discussion of the growth story of the future, the transition to the low-carbon economy.

Yet the local politics of a country of less than 25 million is being allowed to prevent essential strategic discussions of an issue that is of fundamental importance to the prosperity and well-being of the world’s population of 7 billion people.

As Giles Parkinson told radio National

- essentially what the IPCC is saying to Australia is, on its current policy settings, ‘wrong way, go back’.

Here’s Abbott in visionary mode:

Carrington above provides a useful summary of the IPCC report. Jones identifies a change in approach:

- Instead of dealing largely in forecasts and responses, as in previous syntheses, it now frames the climate problem squarely in terms of risk management.

Jones then identifies some of the myths the report busts. Roz Pidcock at The Carbon Brief identifies what’s new and interesting about the report.

C. Forbes Tompkins and Kelly Levin at Climate Code Red list 9 significant scientific findings too recent to be included in the new IPCC report. Two of them relate to sea level rise, an increased fragility of both the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets.

There are more links at the end of the post. I wish to comment on the appropriateness of the 2°C guardrail, the view of risk taken in relation to the 2°C and then some conclusions.

Is a 2°C temperature rise safe?

David Spratt addressed this issue in September 2013. To summarise some of what he said:

- The tipping point for Greenland Ice Sheet has been revised down to +1.6ºC (uncertainty range of +0.8 to +3.2ºC) above pre-industrial. We are likely to hit +1.6ºC within a decade or two.

- It has been shown that “preserving more than 10 per cent of coral reefs worldwide would require limiting warming to below +1.5°C (atmosphere–ocean general circulation models (AOGCMs) range: 1.3–1.8°C) relative to pre-industrial levels”.

- Large-scale thawing of permafrost may have already started, but a 1.5ºC global rise in temperature compared to pre-industrial should be enough to start a general permafrost melt.

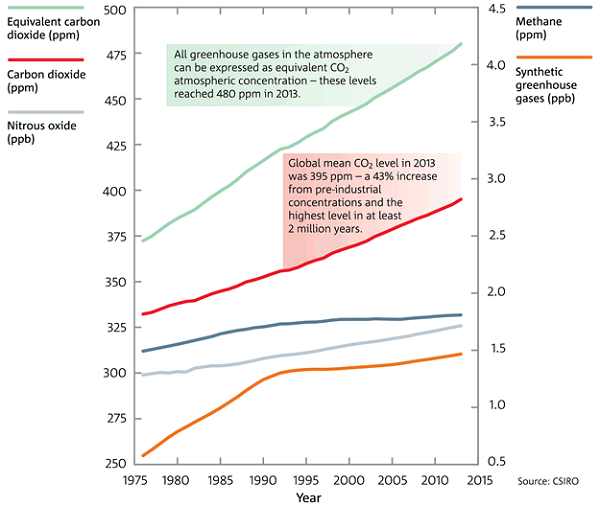

- Current levels of CO2 at about 400 ppm place us in the Middle Pliocene epoch (3.0–3.5 Myr ago) when sea levels were 25m plus or minus 5 higher than now.

- During the Eemian 123,000 years ago sea-level rises of 3 metres occurred within 50 years due to the rapid melting of ice sheets, when the energy imbalance in the climate system was less than at present.

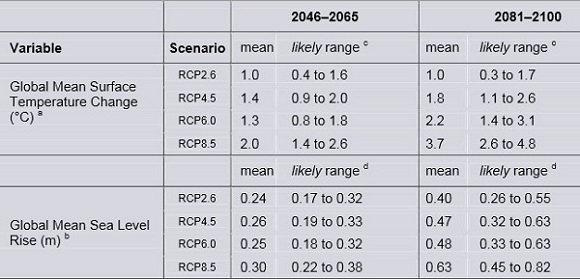

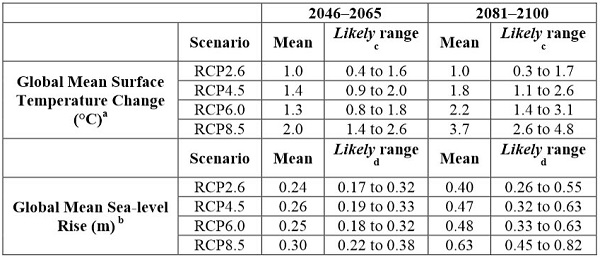

On sea level rise, here are the projections given in the Long Report p. 60:

In a footnote we are told:

- Based on current understanding (from observations, physical understanding and modelling), only the collapse of marine-based sectors of the Antarctic ice sheet, if initiated, could cause global mean sea level to rise substantially above the likely range during the 21st century. There is medium confidence that this additional contribution would not exceed several tenths of a metre of sea-level rise during the 21st century.

They’ve covered themselves on Antarctica, but missed the fragility of Greenland. On page 30, they say this:

- There is low confidence in the available models’ ability to project solid ice discharge from the Antarctic ice sheet. Hence, these models likely underestimate the Antarctica ice sheet contribution, resulting in an underestimation of projected sea-level rise beyond 2100. (p30, Long report)

On sea level rise unfortunately for the next seven years we will be quoted the means given in the tables, without the qualifications, which themselves are inadequate in the late of the latest science. So the talk will be about half a metre, or up to a metre maximum.

For these and the other reasons quoted, plus a few I didn’t highlight, a 2°C guardrail looks foolhardy to say the least.

View of risk taken in relation to the 2°C

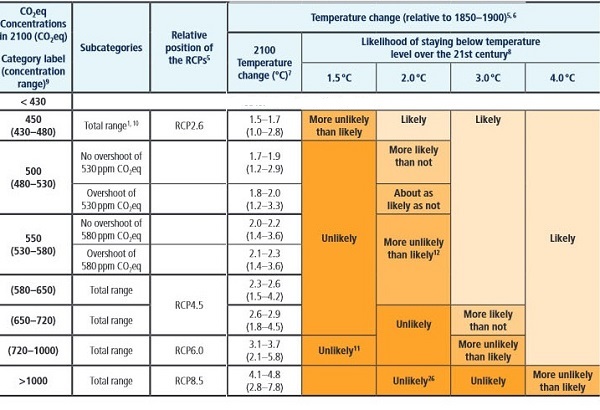

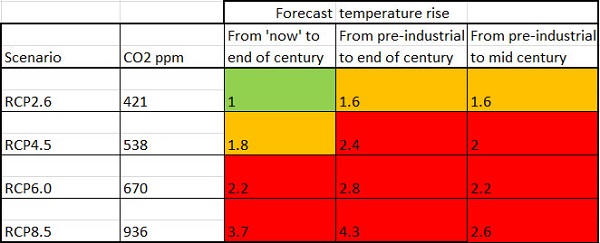

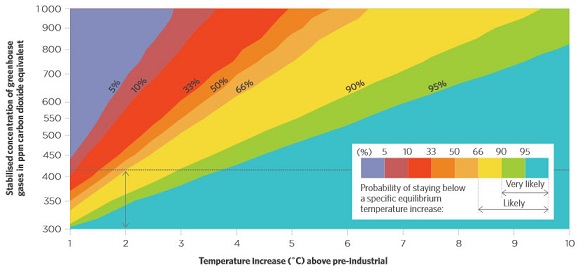

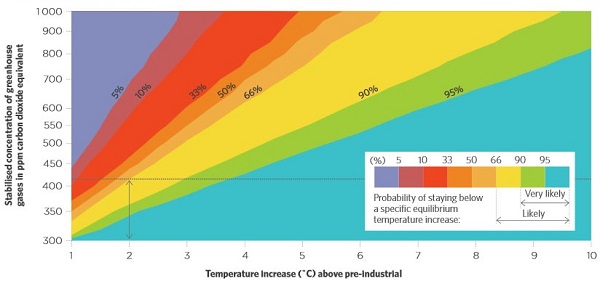

This table gives some overview of the relationship between the emissions levels, RCP scenarios, temperature change and the likelihood of staying below various temperature levels. I’ve actually taken the table from Working Group 3 and adapted it by taking out four columns (relating to quantums of CO2 and emissions reduction targets for 2050 and 2100) to highlight the broad relationships:

Much of the same information is given in the table on p23 (Short Report) and footnotes.

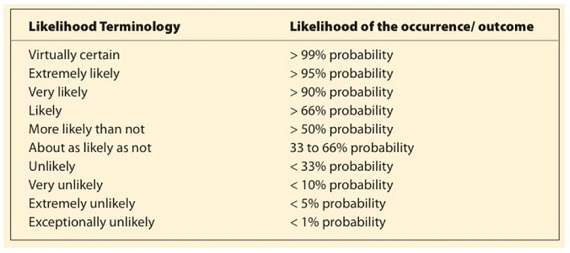

In the Short Report (p15) we are told that CO2e levels in 2011 were 430 ppm. Unfortunately the CSIRO/BOM State of the climate report says that in 2014 we are at 480 ppm of CO2 equivalent. So realistically the best on offer is the 500 zone with overshoot. This sees us with a likely as not chance of staying below 2°C. Here’s what the official language means:

In other words a 33 to 66% chance of staying below 2°C, or if we act quickly and drastically a 66% chance. When you consider the implications even of a 1.5°C climate, this is desperately insane and simply not acceptable.

David Spratt suggests a risk-averse (pro-safety) approach, say, of less than 10% probability of whatever target we deem appropriate. I’d suggest a less than 5% probability of a 1.5°C temperature rise and then see whether that is doable. Are we game to talk about what really needs to be done for a livable, sustainable ecosystem for future generations? Or are we going to continue eating our children’s future?

Conclusions

Back in 2007 environmentalist Bill McKibbin asked James Hansen what the appropriate levels of CO2 should be. Hansen gave his answer in December 2007 at the American Geophysical Union meeting. At that very time the UNFCCC Conference of Parties was meeting in Bali. Hansen’s response was that we had overshot and that we should aim at 350 ppm by taking CO2 out of the atmosphere. To clarify, Hansen’s answer assumed that we would achieve net zero in other greenhouse gases, so he was really talking about CO2e. McKibbin went off and started up 350.org.

In a strict sense the IPCC Report is agnostic about a 2°C guardrail. It simply identifies risks, vulnerabilities and impacts at various temperature levels. However, when it comes to mitigation scenarios, it deals with what is out there in the scientific literature. Here it seems the vast bulk of the modelling contemplates scenarios where the 2°C guardrail is simply part of the furniture. Yet what has been called CCS (carbon capture and storage) and the report (see Short Report p.15 for example) re-badges as CDR (carbon dioxide removal) is also part of the furniture.

It seems to me that the scientific community is struggling to catch up with where Hansen was seven years ago. Perhaps they are concentrating on what’s doable, but at the same time they are holding out false hope. While the world’s scientists and governments have issued their bluntest warning yet, we seem to be letting go the idea of a safe climate. I heard head honcho Rajendra K Pachauri on the radio saying that we only had a budget of 275Gt of carbon (that’s about 1000GT of CO2) left that could be used. In fact, rationally, we don’t have a budget at all, we are in the red. Rationally, all the fossil fuel reserves should be left in the ground – all of them, unless offset with CCS or CDR, for which our visionary PM has just slashed the research budget.

Update:

Al Jazzeera rounds up some of the opinion warning that 2°C is foolhardy and dangerous.

- “There is no such thing as a safe rise,” said Bob Watson, who was the chair of the IPCC from 1997 to 2002. “You will see food and water insecurity, human health problems, and sea level rise even with a 2 C rise.”

And so on.

See also:

UN Climate Report Rings Alarm, Offers Guidance

World’s Scientists Warn: We Have ‘High Confidence’ In The ‘Irreversible Impacts’ Of Climate Inaction

Media round-up: The IPCC synthesis report

That last link from The Carbon Brief is quite comprehensive and includes a list of their six posts.

Related IPCC posts, in chronological order:

Crisis or catastrophe? What will the IPCC say?

A choice of catastrophes: the IPCC budget approach

Commentary on IPCC WG1: Part 1

Commentary on IPCC WG1: Part 2

Climate change impacts: IPCC Working Party 2 report

Adding to the muddle? The IPCC climate change mitigation report

Below I’ve set set out some of the main findings in the Summary for Policymakers (downloadable from

Below I’ve set set out some of the main findings in the Summary for Policymakers (downloadable from