1. Unburnable Carbon: Why we need to leave fossil fuels in the ground

That’s the title of a new report from the Climate Council.

To have a 75% chance of meeting the 2°C warming limit, at least 77% of the world’s fossil fuels cannot be burned.

1. Unburnable Carbon: Why we need to leave fossil fuels in the ground

That’s the title of a new report from the Climate Council.

To have a 75% chance of meeting the 2°C warming limit, at least 77% of the world’s fossil fuels cannot be burned.

The federal Government’s forays into health policy show no signs of becoming realistic. The 2014 budget foreshadowed that the Commonwealth might get out of the funding of hospitals in favour of the states accepting a higher and broader GST.

The problem here, as Gillard pointed out in her book, is that health expenditure expands faster than the GST revenue.

Then we had $7 co-payments for GP visits in an effort to keep poor people out of doctors’ surgeries.

This was followed by the fiasco of proposing and dumping the $20 cut to the rebate for short GP visits. According to recent news reports, the plan was originally opposed by Joe Hockey and then health minister Peter Dutton. Abbott insisted and then unaccountably backflipped.

Now Joe Hockey reckons we are living too long. Some kid just born somewhere is bound to live to 150.

John Dwyer, Emeritus Professor of Medicine at the University of NSW, has long been an advocate for preventative health care. He says in a paywalled article in the AFR that many hospital admissions (costing $5000 each) could be prevented by primary care intervention in the three weeks prior to admission.

Medicare expenditure of $19 billion each year is dwarfed by hospital expenditure of $60 billion.

There is now an abundance of evidence that a focus on prevention in a personalised health system improves outcomes while slashing costs. Some systems have reduced hospital admissions by 42 percent over the last decade.

The Brits have just been presented with a review that concluded that an extra $132 million (in our money equivalent) spent on improving primary care would save the system $3.5 billion by 2020.

Worth a look, I would think!

There is another problem in the works. Only 13% of young doctors express any interest in becoming a GP.

The discrepancy in income potential for GPs when compared to that of other specialists is now huge. Young doctors looking at the professional life of our GPs are uncomfortable with the current “fee-for-service” model that encourages turnstile medicine that is so professionally unfulfilling. Many GPs join corporate primary care providers preferring a salary.

New Zealand has facilitated 85% of GPs away from fee-for-service payments. The same is true in the US for 65% of primary care physicians.

Finally, says Dwyer, we could take the $5 billion cost of the private health insurance rebate and spend it on all of the above.

Once again we are embarrassed by the incompetence of our politicians.

I’ve been cracking my brain over one of Getup’s latest campaigns – keeping medical insurers out of the direct provision of primary health care.

The issue has come to a head with the federal government’s review of the $1.8 billion Medicare Local scheme. In brief, the 61 existing Medicare Locals are to be consolidated into 30 Primary Health Networks (PHNs), with geographic boundaries aligned with the existing Local Hospital Networks. The Government is about to call tenders for the provision of PHN services, with private medical insurance companies able to tender.

The Government does appear to have crossed a line, which is a concern, but my question is what does it mean to me, my relationship with my GP, and will it constrain her in pathways to care and access to specialist services? Getup’s concerns:

This means insurance companies, and not your GP, could end up making critical decisions about who gets treatment and how we’re treated, with health groups already raising the alarm. It’s the very system that’s crippled American healthcare, driving up costs and leading to less care for fewer people.

Profit-driven healthcare threatens the very foundation of our universal Medicare system, restricting access and quality of care, especially in areas where insurers don’t stand to make money.

Frankly, I can’t see that Medicare Local meant anything to my healthcare and I doubt that anything will change with the introduction of PHNs in July next year.

I’m struggling to understand what a Medicare Local does. This is from Professor John Horvath’s review (p. 8):

As part of the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) National Health Reform Agreement (2011), the Commonwealth Government agreed to fund Medicare Locals to improve coordination and integration of primary health care in local communities, address service gaps, and make it easier for patients to navigate their local health care system. Medicare Locals are expected to fully engage with the primary health care sector, communities, the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) sector, and Local Hospital Networks (LHNs). Their establishment was built on the foundations of Divisions of General Practice (DGPs).

According to Horvath Medicare Locals also struggled to know what their role was. A critical phrase is “address service gaps”. Horvath says Medicare Locals were never intended to offer services in competition with existing services, but in fact that is what many did.

Medicare Locals were established in three tranches from 2011 as not-for-profit companies. Horvath says the PHNs should be contestable, transparent and accountable. He says that they should be be companies incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001, have skills based boards and should “establish a Clinical Council and a Community Advisory Committee in each LHNs (or clusters of LHNs) with which they are aligned as ‘operational units’” (p.17 of his Review). I suspect the involvement of for-profit health insurance companies would surprise him.

In Horvath’s “vision and design principles” statement (p.16) the closest PHNs would come to the direct provision of services is this:

Not all regions across Australia are equally serviced. The role of the PHO is to work with the GPs, Commonwealth and state health authorities, LHNs, and communities to identify gaps in health services and work in partnership with these organisations to source the appropriate services.

Yet in this article it is clear that Medicare Locals are providing services in remote areas that otherwise would be unserviced. And then this:

The Federal Assistant Minister for Health, Fiona Nash, said Primary Health Networks will not be providers of services, as some Medicare Locals have been.

The Young based Senator said a problem with Medicare Locals was a lack of direction but PHNs will have a clear set of guidelines.

“They’re going to be regional purchasers of health services and providers only in the exceptional circumstances,” Senator Nash said.

I remain confused.

It seems to me that Horvath saw PHNs as supportive rather than supervisory. Yet purchasing services does put them in the authority line in the provision of services. If so, there is a conflict of interest problem with the involvement of for-profit medical insurance companies.

Contra Getup, I don’t have an objection to for-profit companies providing health care. We have shares in a company called Ramsay Health Care which owns and runs hospitals. The provision of quality service seems to be their niche. As it happens I’ve had operations in two Ramsay hospitals as well as one owned by a bunch of specialist doctors, plus The Wesley, which is Uniting Church. Only in the one owned by doctors did I have concerns about the service, and then not all that serious.

Nevertheless we need to be alert and perhaps alarmed about situations where bean counters have undue influence on the provision of medical services. That can happen in the public sphere as well as the private.

Certainly in this case alarm is not confined to Getup. Nurses are also concerned.

Elsewhere Croakey consults the experts.

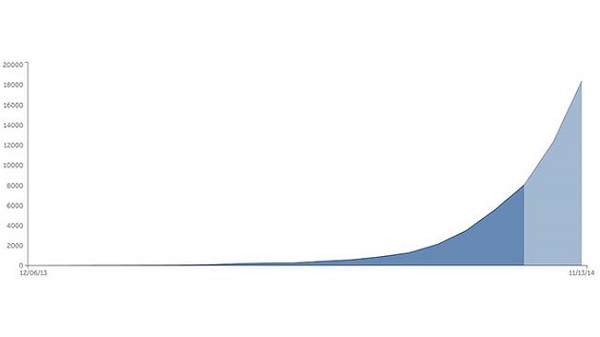

In Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, three neighbouring West African countries, Ebola seems to be out of control. This is a graph of the numbers of new cases with projections for the next four weeks in lighter blue:

So far there have been about 8,400 cases and some 4,000 deaths. There are claims that cases in Liberia are doubling every 15-20 days while those in Sierra Leone are doubling every 30-40 days. By the end of the year there could be as many as 18,000 new cases weekly.

I’m impressed though that there has been no spread to other African countries other than Nigeria, where it appears to have been contained. One case surfaced in Lagos in July with 19 subsequent infections. However, the chain of contagion seems to have been broken.

On the other hand subsequent infections in the US, where a second health care worker has tested positive, and Spain are cause for concern.

You can read very different views of the potential impact of the disease worldwide. This Nature article is quite definite that the Ebola does not represent a global threat. The virus is too hard to catch and advanced country health systems are too sophisticted. By contrast this New York Times piece worries about the virus gaining a foothold in a mega-city somewhere else in the developing world. I’d worry about India and the capacity of its health system to cope.

The current outbreak is the first time the disease has gained a foothold in urban areas.

A second worry is that the virus may become airborne. C Raina MacIntyre, who is Professor of Infectious Diseases Epidemiology and Head of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine at UNSW, points out that experienced health care workers who have contacted the disease have not been able to identify how they caught it. The assumption is simply that there has been a breach in protocol. We keep being assured that the disease is hard to catch. While the long incubation phase, up to three weeks, does not help memory, the fact that it keeps happening in ways that can’t be precisely pinpointed is troubling.

Still, the circumstances that saw the disease take hold in West Africa are unlikely to be repeated. This Vanity Fair article explains how the spread of Ebola was assisted by unique circumstances.

Firstly Ebola was not identified for three and a half months. The disease was virtually unknown in West Africa; earlier outbreaks had been in central and east Africa. At first cholera, then Lassa fever were suspected. By the time Ebola was identified the disease had already spread to a number of towns, including a bustling trade hub.

The reaction of first world agencies was swift. After identification in late March, Guinea was invaded by strange robotic white people who came in space suits and took ill people away.

The foreigners had come so fast that they had actually out-run their own messaging: there were trucks full of foreigners in yellow space suits motoring into villages to take people into isolation before people understood why isolation was necessary.

To a villager, the isolation centers were fearsome places. They offered a one-way maze through white tarpaulins and waist-high orange fencing. Relatives or friends went in and then you lost them. You couldn’t see what was happening inside the tents—you just saw the figures in goggles and full-body protective gear. The health workers move carefully in order to avoid tears and punctures; from a distance, the effect is robotic. The health workers don’t look like any people you’ve ever seen. They perform stiffly and slowly, and then they disappear into the tent where your mother or brother may be, and everything that happens inside is left to your imagination. Villagers began to whisper to one another—They’re harvesting our organs; they’re taking our limbs.

The people in Guinea were as frightened by the response to Ebola as they were by Ebola itself. By May the cases dried up and the aid agencies started to relax. In fact the sick were hiding, as soon became apparent.

Rather than under control the reverse was true, the epidemic was completely out of control. While new strategies are gaining the trust of the people, the disease has outrun attempts to contain it.

There must be a huge effort to contain the disease within the three countries where then disease is endemic while a vaccine, currently under development, is fast tracked. As to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, we can’t just write off a combined population of over 20 million people. Health workers are in the front line and these countries human health worker resources are being depleted by the disease. Liberia has only 250 doctors left for 4 million people, that’s one for every 16,0000 people.

Yet Australia has seen no great obligation to help. Officially I understand we have supplied about $18 million in aid, a pathetic amount, while our fearless prime minister has said that it is too dangerous for us to put boots on the ground. Yet there is work to be done out of direct contact with patients, in building temporary field hospitals, for example. Our PM could show just a bit of compassion and genuine humanitarian concern.

Along with apologising comprehensively to the Chinese, yesterday Clive Palmer announced that the proposed GP co-payment was not going to happen. Not one cent, he said. Palmer was effectively saying that as a wealthy country we can afford the health system we’ve got.

Well, I think that there won’t be a $7 co-payment. It’s just media beat up, you know, it’s not going to happen. And, you’ve got to remember that in Australia we spend 8.9 per cent of our GDP on health. In the United States they spend 17.2 per cent of GDP on health, yet 60 million Americans have no coverage.

I’m not sure he’s right about 60 million Americans having no coverage. In my mind it was 40 odd million and that was before Obamacare. fROM MEMORY bout the same number who are ‘food insecure’, that is they aren’t sure whether they will eat tomorrow.

Minister Peter Dutton, however, was saying that we need the co-payment because the health system is unsustainable. In other words, in the government’s view, we need as a matter of social and economic policy the poor to go to the doctor less. However, GP services are recognised as being in the front line as preventative medicine. Ignoring the health welfare of the poor, health policy aficionados question whether the co-payment would not actually cost the system more in the long run.

We can’t assume that the Government actually knows what it wants to achieve with its policy. Laura Tingle finds the government’s position completely muddle-headed and inconsistent.

No matter how much it may now criticise the AMA proposal, no matter how large a hole the proposal leaves in the budget, the government is yet to find its own way through the debate, or even clarify what the actual aim of its policy really is.

Apparently the AMA proposal, the one Tony Abbott personally asked them to put together, eliminated 97% of the projected budget savings. But Tingle says that it dealt with the equity problem and addressed

the very issue the government said it wanted to deal with when it first raised the idea of a Medicare co-payment before the budget.

That is, that those who can afford to make a contribution to the cost of going to the doctor should do so.

It should be remembered, I think, that savings from the GP co-payment initiative would not be used to pay off the deficit. Rather a research fund was going to be established which was going to save the nation, having lost the car industry, and find a cure for cancer. Or something.

Yet minister Pyne can threaten to take the savings out of general university research funding if his proposals re universities are not passed.

This is a government that far from tackling problems in an orderly way as they claim is resorting to ad hoc threats and bullying rather than deliberative policy processes. Part of the problem is accommodating Abbott’s signature policy initiative, the paid parental leave scheme. As Tingle says in this article:

Wherever Hockey, or other ministers go trying to sell the budget, for example, they have to try to explain how its paid parental leave scheme fits with spending cuts that hurt low-income earners hardest.

All during the 2013 election campaign Kevin Rudd warned voters that Abbott would “Cut, cut and cut to the bone” just as Campbell Newman had done in Queensland. Commentators have remarked on Abbott’s lack of a honeymoon period. Campbell Newman certainly had one, but has now spectacularly squandered his political capital in various ways.

All during the 2013 election campaign Kevin Rudd warned voters that Abbott would “Cut, cut and cut to the bone” just as Campbell Newman had done in Queensland. Commentators have remarked on Abbott’s lack of a honeymoon period. Campbell Newman certainly had one, but has now spectacularly squandered his political capital in various ways.

Dominating headlines for weeks on end the doctors’ dispute seems to have become something of a tipping point. Mark at his new blog The New Social Democrat has published an excellent link-filled post Newman v the doctors: a political fight that is poisoning the LNP, originally published at Crikey.

Mark sees the changes proposed in doctors’ conditions as carrying a broader warning for Australian health policy:

The contracts, read in conjunction with changes to the Industrial Relations Act, deny salaried doctors unfair dismissal protections, control over work location and timing of shifts, and require doctors to take direction on appropriate medical care from hospital and health service administrators.

The suggestion is that, having failed to find private operators for public hospitals that could actually provide cheaper services, the government’s agenda is to substitute bureaucratic cost controls for clinical judgement. That’s something the federal policy shifts towards paying hospitals for the “efficient price” of a procedure encourages. (Emphasis added)

The ground is shifting politically:

None of this is a good look for a government that recently lost the Redcliffe byelection to Labor with a massive swing. Polling conducted by ReachTEL for the Australian Salaried Medical Officers’ Federation in Ashgrove (the Premier’s seat), Cairns, Ipswich West and Mundingburra shows massive public opposition and significant impacts on the LNP’s vote. Newman would easily lose his seat to the ALP on these numbers, and it could be reasonably inferred that the LNP’s majority would be in danger.

Readers may recall that in 2012 Anna Bligh spectacularly crashed and burned, losing 44 of 51 seats to be left with seven in an 89-member parliament. With a walloping majority “Can do” Campbell may do the impossible and become a one-term government. A tweet from Possum Commitatus quotes a ReachTEL poll which says that if an election were held now the LNP would lose 36 seats and government.

Newman has looked gone in his own seat for some time. If people think he’s not OK as leader let them ponder the alternatives!

Elsewhere Kiwi doctors stand in solidarity with their Qld colleagues and are being advised to stay well away.

The electorate is volatile. Abbott be warned!

Over the past two weeks the ABC’s Catalyst program has run a special series under the rubric The Heart of the Matter calling into question the importance of cholesterol as a risk factor for heart disease with Dr. Maryanne Demasi leading the charge. This is how she described the programs:

In the first episode of this two part edition of Catalyst, I investigate the science behind the long established view that saturated fat causes heart disease by raising cholesterol.

In the second episode, I cut through the hype surrounding cholesterol lowering drugs and reveal the tactics used by Big Pharma to make the drugs to lower cholesterol appear more effective than they seem to be.

In Heart of the Matter, I investigate whether the role of saturated fat and cholesterol in heart disease is one of the biggest myths in medical history.

Go here for transcripts and videos:

First up it must be said that Dr Demasi is not just a journalist. She has a PhD in medical research from the University of Adelaide and worked for a decade as a research scientist specialising in rheumatoid arthritis research at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

I had a triple bypass back in 2000 and have taken statins ever since as well as 100mg aspirin daily and medicine to lower my blood pressure. Except on rare occasions saturated fats do not pass my lips.

Dr Norman Swan told Fran Kelly that his wife had sat next to someone on a plane who had been taking statins for familial high cholesterol levels. After seeing the program he said he had dropped the drugs and was going to tuck into the cream cheese.

To this viewer, such a response would be warranted on the basis of the evidence put forward in the programs. I’m a cautious person, however, so my intention was to stay on course, but was going to consult my GP who I see every four to six weeks. I expected her to advise me to change nothing until I next see my cardiologist in March next year.

Norman Swan was angry. He said people will die as a result of the program. Continue reading The Heart of the Matter

These posts are intended to share information and ideas about climate change and hence act as a roundtable. Again I do not want to spend time in comments rehashing whether human activity causes climate change.

These posts are intended to share information and ideas about climate change and hence act as a roundtable. Again I do not want to spend time in comments rehashing whether human activity causes climate change.

This edition is mostly about the doings of our new government, prospective EU targets, a statement by religious leaders and a couple of items on health implications.

Whether or not Greg Hunt gets to go to the UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) Conference of Parties (COP) in Warsaw from 11 to 22 November. Julie Bishop will henceforth be the lead negotiator in international climate talks.

The story in the AFR says Hunt has been “stripped of responsibility for global climate change negotiations”. He still gets to go and hang out at the talks. One might say that Australia’s representation has been upgraded. Suspicious minds might also think that Hunt couldn’t be trusted. He actually believes human activity causes global warming and might join the warmist urgers if not kept on a tight leash. Continue reading Climate clippings 84

According to Oxfam 21,000 people died due to weather-related disasters in the first nine months of 2010 – more than twice the number (10,000) for the whole of 2009. Their information comes from reinsurance company Munich Re.

The number of extreme weather events was 725 to September, as against 850 for 2009. The number of extreme events is likely to exceed the ten-year average of 770, but not by a large margin. This year included some particularly serious ones, such as the floods in Pakistan and the heatwave in Russia.

The Pakistan floods affected more than 20 million people, submerging about a fifth of the country, claiming 2,000 lives and causing $9.7 billion in damage. Summer temperatures in Russia exceeded the long-term average by 7.8°C, doubling the daily death rate in Moscow to 700 and causing fires that destroyed 26 per cent of the country’s wheat crop. Russia banned grain exports as a result and soon after world grain prices increased, affecting poor people particularly.

Statistics relating to extreme weather events are tricky. The number of deaths obviously relates to the severity of the individual events and how many people were living in areas where the events occurred and hence vulnerable. Continue reading Climate kills