Around 80 to 85% of coal in the ground cannot be mined by conventional methods. That’s 18 trillion tonnes according to the International Energy Agency’s Clean Coal Centre – enough to supply the world for 1000 years, at current requirements. Fred Pearce in the New Scientist (paywalled) takes a look at efforts to liberate this potential by a process called underground coal gasification (UCG). Apparently that’s enough to add about 10°C to global warming, if the carbon is not sequestered.

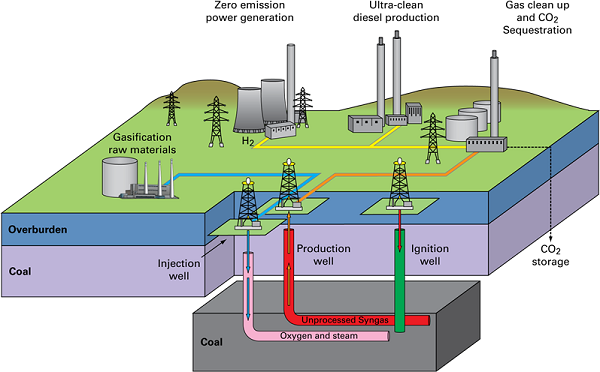

The process involves burning the coal in situ underground, bringing the gases thus created to the surface and then burning them in a conventional power station. This image from the British Geological Survey illustrates the process:

The “Zero emissions power generation” is totally misleading (see below).

Stalin’s engineers and their successors have been doing it to a brown coal seam for 50 years near Angren, a town east of Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Air is piped 300 metres down one well, the gas comes up another. It is cooled, scrubbed of coal dust and compressed on site, then piped across the plain to Angren. Australians bought the operation seven years ago, with a view to scaling up the technology to transform the world’s energy markets.

A cocktail of gases is created when the coal is burned – methane (natural gas), CO2, which can be disposed of safely, carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen. There are four ways the gases can be used:

- Gas to electricity. Methane is burned in a power station.

- Gas to chemicals. Hydrogen, methane and CO have value as feedstock in the chemicals industry.

- Gas to liquid. Methane can be liquified to LNG, or CO and hydrogen can be turned into synthetic diesel.

- Gas to tech. Hydrogen can be used as a transport fuel.

As methane burns it oxidises to CO2 and water. Potentially, it is said, the same infrastructure of pipes can be used to pipe the CO2 from the power station back to the mine and insert it in the place vacated by the burnt coal. Obviously you’d have to double the pipeline for continuous operation. And obviously the process would add to the expense.

A second concern is that chemicals can leak to contaminate groundwater. If the rocks above the seam are impermeable before the process, they may not be after. Fracturing is estimated to occur up to 60 times the width of the seam. In fact fracturing the nearby rocks could release even more gas for use.

Australian engineers trialled an adapted process at Chinchilla in Queensland in the 1990s. Within two years UCG was shown to be feasible. But in 2011 benzene and toluene leaked into a nearby borehole in an operation near Kingaroy. Similar problems had emerged in the US, so Qld authorities shut the operation down for investigation. Last July ‘Can do’ Campbell’s mob came up with the idea that you could only operate if you successfully decommissioned a commercial scale operation to show that you could do it. So you had to start an operation, stop it, get your operating ticket, then start up again. Brilliant!

There were three companies involved in Qld – Linc Energy, Carbon Energy and Cougar Energy. They responded by shutting Chinchilla down after more than a decade of successful production, and relocating to China, the US, Argentina, Chile and Indonesia.

There are trials elsewhere, including Canada and South Africa. At Cook Inlet in Alaska and Swan Hills in Alberta, Canada, there are plans to go commercial as early as 2015. In Britain, they reckon 70% of coal has never been mined. Furthermore there is 10 billion tonnes of the stuff under 400 square kilometres in the North Sea. An Office for Unconventional Gas and Oil has been set up with £1 billion seed money to stimulate the industry. Half a dozen start-ups have been spawned. There is interest also in supplying feedstock to energise the flagging chemicals industry in Scotland.

All this momentum is a worry unless in practice ‘clean’ coal turns out to be completely clean. For example in Britain it is said that only 30% of CO2 could be sequestered. There they are throwing £1 billion at the problem.

Remember, for a safe climate we need to reduce the concentration of emissions initially to 350 ppm. Or you can go back and depress yourself by re-reading The game is up.

Our best chance lies in the possibility of renewables becoming cheaper than the fossil alternatives. If we rely on the human race acting rationally in its own longer term self interest our prospects are not good.

These posts are intended to share information and ideas about climate change and hence act as a roundtable. Again, I do not want to spend time in comments rehashing whether human activity causes climate change.

These posts are intended to share information and ideas about climate change and hence act as a roundtable. Again, I do not want to spend time in comments rehashing whether human activity causes climate change.