Six years ago I penned a post Last exit on the road to Perdition. It began like this:

“Damn! I think we just passed the last exit for the Holocene!”

“I’m sorry, honey, I wasn’t looking.”

“We have to get off this highway. What’s the next exit?”

“It’s a long way ahead. Goes to somewhere called Perdition.”

Those words were from a column by Gwynne Dyer, who had just spent a couple of months talking to leading climate scientists and security officials for his book Climate Wars (2009). He saw no happy outcomes.

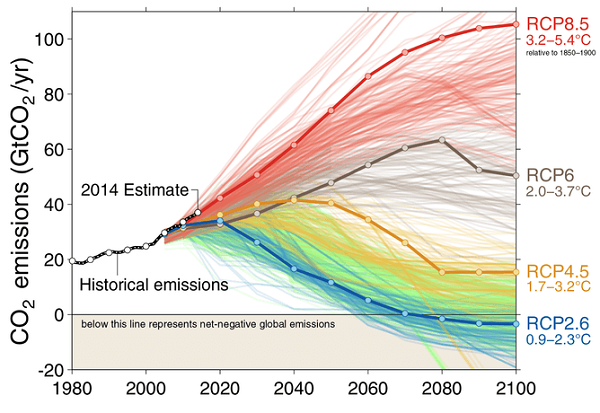

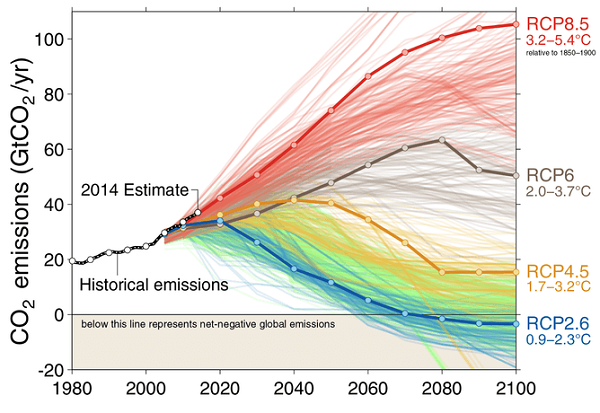

Unfortunately the post falls in a gap in the Larvatus Prodeo record in 2008, but I was reminded of the analogy when I saw this graph from the Global Carbon Budget 2014 report (thanks to John D for the heads-up at Saturday Salon; there are articles by Canadell and Raupach at The Conversation and by Mat Hope at Carbon Brief):

Armageddon is RCP8.5 and a 4°C climate. That’s where civilisation as we know it is in play. Also there is nothing to suggest that the climate would stabilise at that level. Vast beds of methane could be released, the tropical forests would likely burn off, fertile river deltas would be flooded, corals could disappear for a few million years and climate could head for 6°C or more.

Canadell and Raupach say that

economic models can still come up with scenarios in which global warming is kept within 2C by 2100, while both population and per capita wealth continue to grow.

2°C is still attainable, which is at best borderline dangerous, but would require beyond zero emissions, that is:

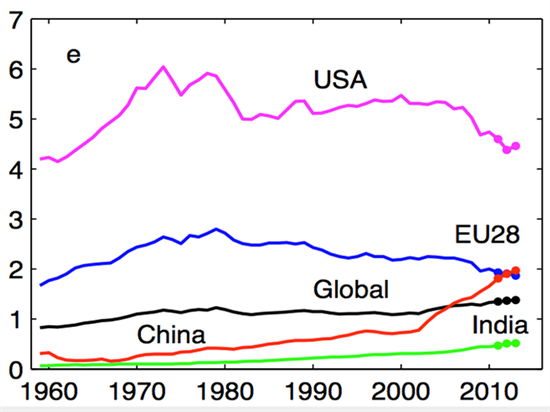

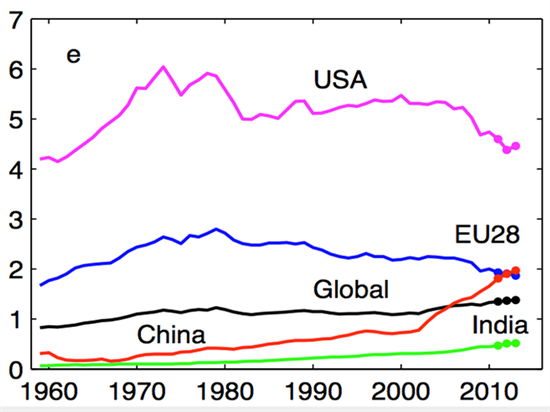

If we keep on growing emissions at 2.5% per annum for a few more years, the best on offer will be peaking by 2040, in other words RCP4.5. That’s the road to Perdition. On current form I suspect that’s where we are heading. The following graph shows that the EU was the only major emitter to reduce emissions in 2013:

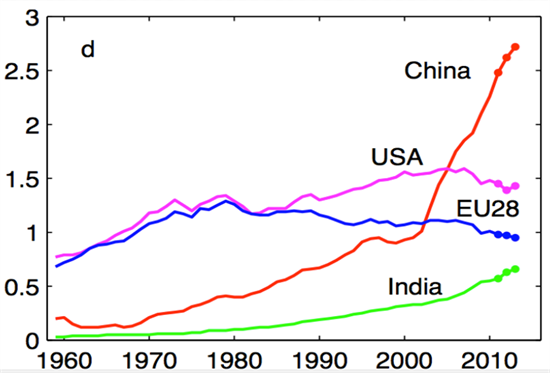

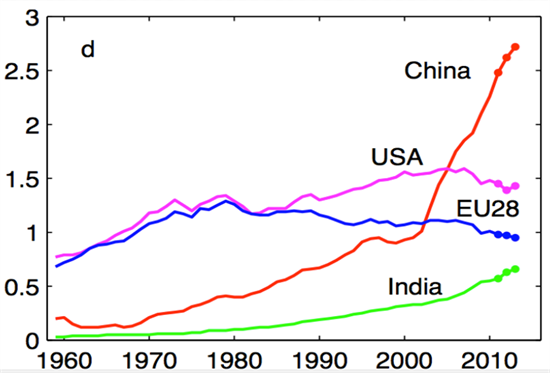

In per capita terms China has now surpassed the EU:

Please note the y-axis is calibrated in tonnes of carbon. For CO2 multiply be 3.67.

As John D pointed out:

There have been other striking changes in emissions profiles since climate negotiations began. In 1990, about two-thirds of CO2 emissions came from developed countries including the United States, Japan, Russia and the European Union (EU) nations. Today, only one-third of world emissions are from these countries; the rest come from the emerging economies and less-developed countries that account for 80% of the global population, suggesting a large potential further emissions growth.

Continuation of current trends over the next five years alone will lead to a new world order on greenhouse gas emissions, with China emitting as much as the United States, Europe and India together.

For a couple of years now, the world had decided that we will make up our minds about what post-2020 targets we will aim for by Paris in December 2015, but the implementation phase does not begin until 2020. Kyoto was a top-down mitigation strategy. This time it will be bottom-up. Every country will set it’s own pace within a framework of “common and differentiated responsibility”. The worry is that the national interest trumps the common good. The UN meeting in New York gave some idea of the early form.

Carbon Brief tried to pick the eyes out of the announcements. Here’s a selection:

- The US has directed federal agencies to consider climate resilience when designing programmes and allocating funds, and will share data from NASA and NOAA and help train developing countries’ scientists. Oxfam says it’s not revolutionary.

- China will peak emissions “as early as possible”. That’s new for official language, perhaps they’ll put a date on it next year.

- The EU will aim to cut emissions by 40% by 2030, subject to confirmation by the European Commission.

- The Netherlands and Belgium both pledged to cut emissions in line with the EU’s regional goal of cutting emissions by 80 to 95 per cent by 2050, compared to 1990 levels. Denmark reminded the conference it aims to be fossil fuel free by 2050.

- India did the usual – called on developed countries to show more leadership, said it would act on climate change, but on its own terms. It aims to double the amount of energy from wind and solar by 2020, they’ve said that before.

- Indonesia said it will cut emissions by 26% by 2020, rising to 40% if it gets international help to do so.

- Malaysia said it has a target to reduce emissions by 40% by 2020, and was on track to do so. Ethiopia said it was still committed to making its economy zero carbon by 2025.

- Some money is flowing into the UN’s Green Climate Fund to help developing countries. France pledged $1 billion, Denmark $70 million, South Korea $100 million, Norway $33 million, Switzerland $100 million, Czech Republic $5.5 million and Mexico $10 million and Luxembourg $6.4 million. Before the summit, Germany had pledged $960m. The EU also announced it would channel $2.5 billion to developing countries during 2014-2015, with a focus on adaptation and mitigation.

- One of the big announcements at the summit was the New York declaration on forests, signed by 27 nations, eight regional governments, 34 multinational corporations, 16 indigenous peoples’ groups and 45 NGOs. It builds on a range of existing agreements including the Warsaw framework for reduced deforestation agreed last year.

The declaration is a voluntary commitment to “at least halve” loss of natural forest by 2020 and “strive to” end it by 2030. It is not legally binding and Brazil, one of the world’s largest rainforest nations, is not a signatory.

All that is fine and good, but frankly underwhelming. As I have already quoted David Spratt:

We have to come to terms with two key facts: practically speaking, there is no longer a “carbon budget” for burning fossil fuels while still achieving a two-degree Celsius (2°C) future; and the 2°C cap is now known to be dangerously too high.

We dawdle towards 2015 and 2020 while options close off or become harder. Perdition looms.