Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, is very clear. While what Bridget McKenzie did may not be illegal, ethically it was wrong. Politicians are elected to serve the public interest, not indulge in behaviour to promote private interests, or further the interests of a political party.

Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, is very clear. While what Bridget McKenzie did may not be illegal, ethically it was wrong. Politicians are elected to serve the public interest, not indulge in behaviour to promote private interests, or further the interests of a political party.

Quite simply, she should resign, or be sacked.

Part of Longstaff’s argument in his AFR opinion piece is that corrupt politicians tend to corrupt others:

Their dodgy behaviour distorts the judgment of citizens. They deploy power in ways that punish the virtuous and reward only those who play their game. We begin by being compromised and end up being complicit.

He says that McKenzie may be a wonderful person, but she has shown herself to be an irresponsible minister who has done wrong and refuses to acknowledge this.

Then:

PM Scott Morrison gave his answer to Sabra Lane this morning (from 6:30 on the counter) – there are some legal issues the Attorney General is “clarifying”, we may learn from this, but the rules were followed, no ineligible projects were funded, the minister has made the decisions, and they were “actioned in an endorsing way by Sports Australia”.

In a sense he’s right about that last bit. Sports Australia should have refused to action decisions improperly made, and so they have become complicit.

The bottom line is that it looks as though the government is going to get away with this scam.

Which is why legal action should be considered.

Here an opinion piece in the AFR Why McKenzie’s sports rorts defence is wrong by Anne Twomey, Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Sydney, becomes relevant. The lead-in summary is:

Australia’s constitutional rulebook doesn’t allow federal governments to splash money on local sports groups without parliamentary approval.

Twomey says that there are at least three areas in which rules are likely to have been broken. Firstly, there is a legal obligation on ministers when acting within the scope of their powers to behave in a manner that is procedurally fair. They can’t take into account irrelevant considerations and they must not act for an improper purpose or in a biased manner.

Clearly there is a basis for what happened to be challenged legally in this regard.

Secondly, there is a question as to whether the minister had any power at all to make these grants. She says:

The Australian Sports Commission (which includes “Sport Australia”) was established by statute as a corporate entity with its own independent legal powers to enter into contracts and make sporting grants.

While Bridget McKenzie had power under section 11 of the Act to give “written directions to the Commission with respect to the policies and practices to be followed by the Commission in the performance of its functions and the exercise of its powers”, this did not allow her to exercise its function and decide who got the grants. In any case, she made no such direction.

Twomey says:

If the minister had no power under statute to make the grants, then this was an invalid expenditure of public money, which is an extremely serious matter.

The third reason relates to the constitution itself. The constitution lists the areas where the Commonwealth Parliament may legislate, for example, external affairs, defence and banking. These are known as “heads of power”. There is no head of power for sport.

She says that the school chaplaincy program ran into a similar problem. The High Court found that direct funding by the Commonwealth was invalid.

So the funding must be channelled through the states which tend to have “more stringent accountability measures, such as codes of ethics for MPs and ministers, strong anti-corruption bodies and legal sanctions.”

In NSW what McKenzie did would likely end up with ICAC (the Independent Commission Against Corruption). Furthermore, in NSW it is a criminal offence to give any property or benefit to any person to influence votes.

That is section 209 of the NSW Electoral Act. If breached a Court of Disputed Returns must declare the election void, as actually happened in 1988 in the case of Scott v Martin.

It seems that who won and why is not relevant, it is the act of attempted influence itself that matters.

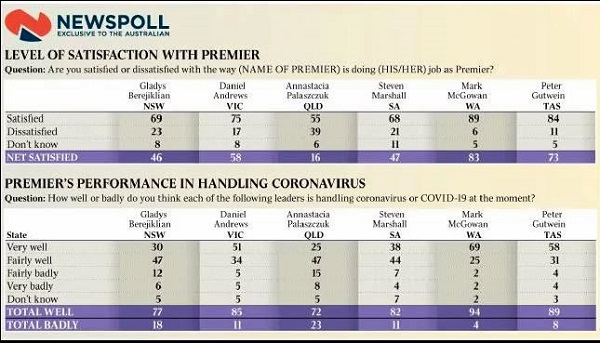

I’m not sure if that would fly under Commonwealth law, but truly, this matter is quite egregious and there should be some form of restitution. Here’s exhibit A, from the Longstaff article:

Earlier post: Bridget’s dreaming and broken democracy

Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, is very clear. While what Bridget McKenzie did may not be illegal, ethically it was wrong. Politicians are elected to serve the public interest, not indulge in behaviour to promote private interests, or further the interests of a political party.

Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, is very clear. While what Bridget McKenzie did may not be illegal, ethically it was wrong. Politicians are elected to serve the public interest, not indulge in behaviour to promote private interests, or further the interests of a political party.