The Japanese have run an actual train with people in it at 500 km/h. The Chinese have built a train which can theoretically run at 1800 mph by encasing it in a vacuum tube.

It looks as though high speed rail could become a real alternative to air for intercity travel.

Thanks to John D for the headsup.

2. World’s first power-to-liquids production plant opens

The world’s first power-to-liquids (PtL) demonstration production plant was opened in Dresden on 14 November. The new rig uses PtL technology to transform water and CO2 to high-purity synthetic fuels (petrol, diesel, kerosene) with the aid of renewable electricity.

The article does not say how efficient the process is, but presumably less so than using the electricity directly.

3. World Bank focus on clean energy

The World Bank has traditionally been one of the world’s largest funders of fossil fuel projects. Now it:

will invest heavily in clean energy and only fund coal projects in “circumstances of extreme need”…

No doubt this policy stems from the bank’s commissioned report Turning down the heat.

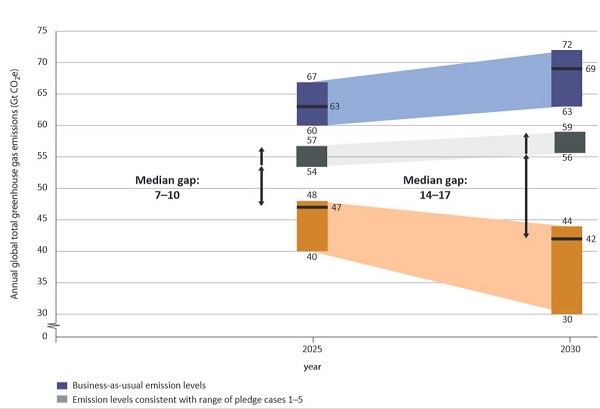

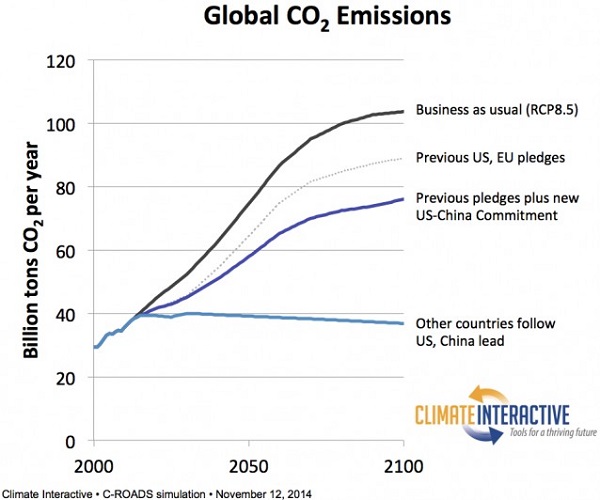

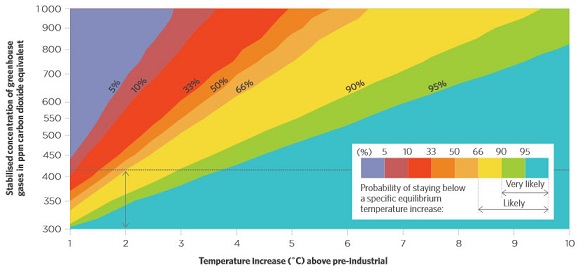

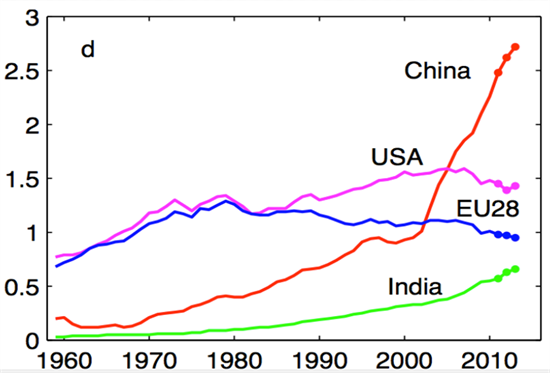

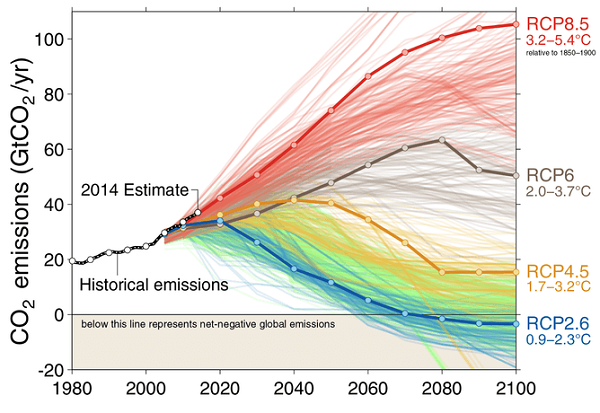

4. Why the Peru climate summit matters

Hope has been injected into the Climate Change Conference in Lima, Peru, scheduled to run from 1 to 12 December by the recent US/China agreement. The optimism stems as much from the fact that the two largest emitters in the world are finally working together as the level of ambition. The EU has also recently pledged to cut emissions by 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2030.

Countries will be working on the text of the draft agreement for Paris in 2015.

Countries are expected to put forward their contributions towards the 2015 agreement in the form of Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) by the end of March [2015]. These will then be used to craft the Paris treaty. The Lima gathering will help provide guidelines and clarity for what these INDCs must entail, especially for developing countries still reliant on fossil fuels to meet fast-growing energy demand needed to achieve developmental goals. These options could range from sector-wide emissions cuts to energy intensity goals to renewable energy targets.

We’ll be represented during the second week by Julie Bishop and Andrew Robb, a climate change denier. Seems Bishop went bananas when she found out, and Robb doesn’t want to be there anyway.

Giles Parkinson reports that we’ve sent a delegation of 14, the smallest in 20 years and probably not enough to be actively obstructive as we were in Warsaw last year.

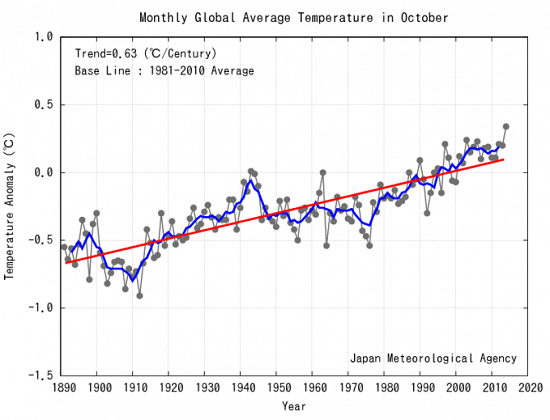

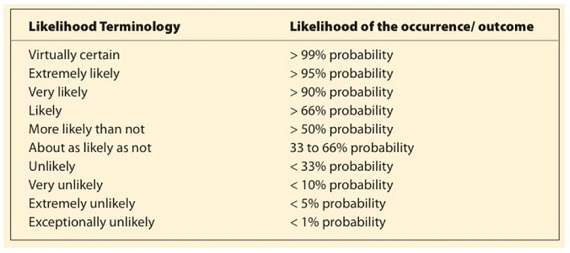

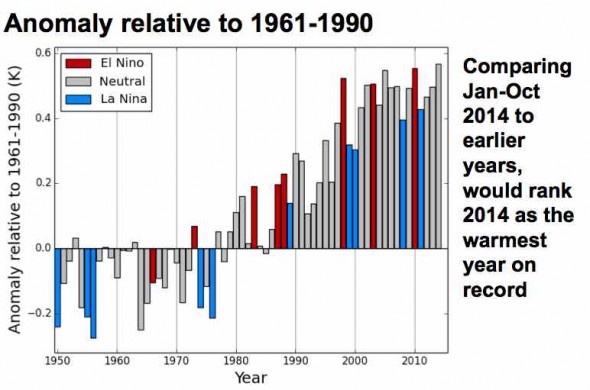

5. 2014 looks like hottest on record

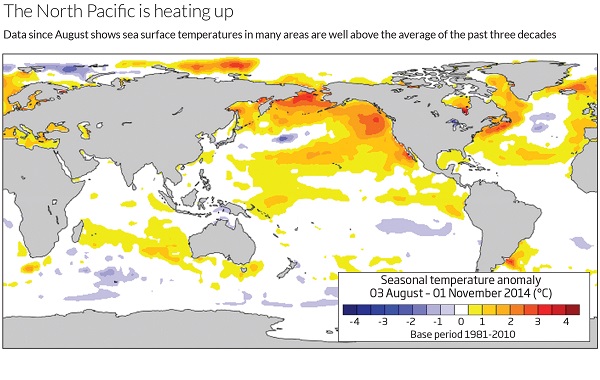

This is how it’s shaping:

Record hot years are often El Niño years. This year is a neutral ENSO year so far.

That’s so far; there is at least a 70% chance that El Niño will be declared in the coming months, according to the BOM. Looks like a hot, dry summer.

6. Germany’s largest utility gets out of the fossil fuel business

On Sunday, Germany’s biggest utility E.ON announced plans to split into two companies and focus on renewables in a major shift that could be an indicator of broader changes to come across the utility sector. E.ON will spin off its nuclear, oil, coal, and gas operations in an effort to confront a drastically altered energy market, especially under the pressure of Germany’s Energiewende — the country’s move away from nuclear to renewables. The company told shareholders that it will place “a particular emphasis on expanding its wind business in Europe and in other selected target markets,” and that it will also “strengthen its solar business.”

E.ON will also focus on smart grids and distributed generation in an effort to improve energy efficiency and increase customer engagement and opportunity.

“With its decision, E.ON is the first company to take the necessary steps from the completely changed world of energy supply,” German Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel, said Monday.

7. The inconvenient truth of EU emissions

The Commission and European Environment Agency’s Progress Report on climate action says:

according to latest estimates, EU greenhouse gas emissions in 2013 fell by 1.8% compared to 2012 and reached the lowest levels since 1990. So not only is the EU well on track to reach the 2020 target, it is also well on track to overachieve it.

Kevin Anderson is not impressed:

The consumption-based emissions (i.e. where emissions associated with imports and exports are considered) of the EU 28 were 2% higher in 2008 than in 1990[1]. By 2013 emissions had marginally reduced to 4% lower than 1990 – but not as a consequence of judicious climate change strategies, but rather the financial fallout of the bankers’ reckless greed – egged on by complicit governments and pliant regulation.

Then he really gets stuck in:

In the quarter of a century since the first IPCC report we have achieved nothing of any significant merit relative to the scale of the climate challenge. All we have to show for our ongoing oratory is a burgeoning industry of bureaucrats, well meaning NGOs, academics and naysayers who collectively have overseen a 60+% rise in global emissions.