Found this interesting article where some experts argue that Sydney train problems could be fixed by halving car registration and removing tolls. It reverses the normal mantra in favour of active and public transport. My take is that the article is asking the wrong questions. The key question that should be asked is “Why do we continue to allow Australia’s mega cities to grow instead of creating new, properly planned cities?” This post looks at other questions that might be asked if we want to make the transport systems of Australian mega cities more workable.

DETAILS:

The transport systems of mega cities like Sydney are becoming more and more onerous as population and area grows. Commute time is growing and growing. It is a particular problem for people who do the service jobs in places like the CBD. For these people the gentrification of inner city ex working class areas means that low paid service workers have to travel a long way to find accommodation that they can afford. (Years ago the SMH commented that teachers and police who work in the CBD have to go over 40 km out from the CBD to find affordable housing.) Part of the problem here is that we have lost the moziac of high and low income residential areas and replaced it with large class areas, something that drives low income people to the fringes of the mega city. (In the past places like Balmain provided places where low income workers could live close to where they worked in the CBD areas.)

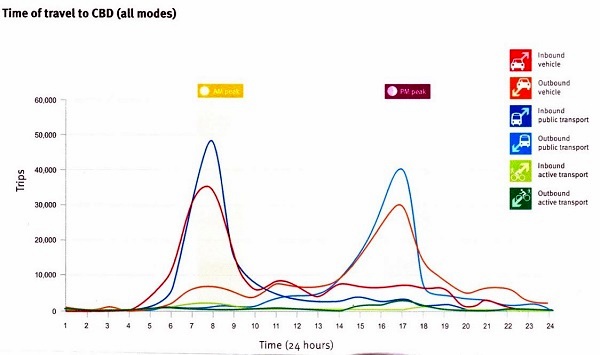

Transport systems have to have enough fixed and mobile capacity to cope with peak hour traffic. The following graph is based on Brisbane traffic to the CBD but similar patterns would apply to other large cities.

Better managing of peak hour traffic is a key strategy for improving transport.

The above problems inspired the following list of questions:

- Do all these people really need to travel during peak hours?

- Can some of these people work at or near home for at least one day a week?

- Could some of these people work in satellite offices closer to home and/or places where they travel against the main flow of traffic during peak hours?

- How do we create places where service workers can live close to places like the CBD?

- How many people would be interested in staying close to work for one or more nights a week? (Including dongas for couples?)

- Should we move to a 7 day roster with only half the workforce going to work on any one day?

- Should we ration travel into the CBD? (Rationed by time slot?)

- Should we ration the number of jobs available in the CBD?

- Why do we allow people to travel in family sized cars with no passengers during peak hours? (For Greater Brisbane on Tues 9/8/11 82.5% of car commutes were driver only with 64.5% of commutes using cars.)

- Why aren’t we developing standards for “commute cars” designed to carry one or two people? (Think of cars one passenger wide that are narrow enough to travel two abreast in a lane and short enough to angle park in a normal street.)

Some of you may want to add to the list or comment on some of the possibilities.

Very topical Brian, given our urban-rural co2 footprint discussion over on the LtG thread, also pertinent questions. Keep in mind we probably will see within a few years more self driving vehicles than conventional electrical cars. Would you believe it, even up here in Cairns we have an experimental driverless bus service based on this.

How does Canberra shape up, we kind of have been down that road before and could perhaps learn from that experience. We do know it’s carbon footprint, it trends the right way, but long way to go.

Ootz: Autonomous cars may make both congestion and emissions worse because there will be cars carrying nobody, cluttering up the roads travelling to the next customer or a parking space.

All the questions aimed at reducing the number of commutes per week or commute distances will reduce both emissions and congestion.

In terms of cars anything that reduces the number of family tanks running driver only will also help both.

The accident avoidance tech being installed in new cars may get us to the point where the tanks designed for crash survival can be replaced with something much much lighter that gets its safety from avoiding accidents.

Narrow track “commuter cars” such as this one designed for driver only commutes could provide independent transport in a vehicle that is narrow enough to travel two abreast in a single lane and short enough to angle park could lead to massive improvements during peak hours.

Some of the questions will make more sense if you look at the peak hour travel graph I have added to the post.

New York Times reports a proposal for a congestion charge on lower Manhattan: $11 for a car and $25 for a truck.

Taxis etc charged by the visit.

Am I the only one not able to see the graph ?

Jumpy: The graph wasn’t there originally and was put in later. Anyone else unable see it? You can also try seeing it in my reference blog.

Ambiguous: All in favour of congestion charges even though parking fees act as defacto congestion charges. Seems to work in Brisbane with about 80% of commutes to the CBD being public and active transport. Compared with 17% for the whole greater Brisbane. (The CBD centric nature of the Brisbane public transport system helps too.)

Brisbane is in the crazy position where all the tolls are on congestion bypasses with no tolls on congested routes. But who can argue? Private is best of course.

Some nice suggestions – but they only tinker at the edges. The worsening situation cannot be avoided until there are some fundamental changes – and the best of luck with getting those changes through.

(1) Abolish outright the 230-year-racket that is the real estate market in Australia. It has caused the growth of unnecessary megacities here; it has wrecked any chance of us having a rational and fair immigration policy; it has destroyed viable industry after viable industry; it has mutilated great swathes of productive farmland and native forests; it has plundered our national treasury, it has rewarded criminal greed.

We can have an honest, non-destructive and widely beneficial real estate market – but not while this racket continues.

(2) Abolish the crazy Centrelink regulation that stops families of the unemployed and grossly under-employed from fleeing the megacities and having a chance to rebuild their lives in small country towns. It is the height of bureaucratic folly to tell someone who will never ever have another full-time job, that they would be leaving an area of high employment for one of low employment – and therefore they must have all their benefits cut. Because of this stupidity – which is a fine example of “government interference in market forces” – small towns all over Australia are being killed off and thousands of houses in small towns remain empty for years and years.

We can cure the megacity disease here – but only if we have courage, vision, energy and a determination to raise the standard of living for everyone, and not just the super-rich, the new aristocracy.

GB: You are right, the questions are largely about making mega city transport systems more workable rather doing something about the growth of mega cities and related problems.

There are three key issues with mega cities like Sydney and Brisbane. They have too many people, cover too much area and have grown up into a poorly planned and operated mess.

It is no coincidence that all the Aus mega cities are state capitals and all are located at what would have been the best port in the state at the time when they started.

Once you have a state capital government depts and public servants start working there. Companies that seek business from the government or have some need to influence government set up head offices there. Other companies set up head offices because they want to do business with other companies who have set up in the capital city and.

Perhaps we need more states and state capitals if we want to take the pressure off the existing mega cities?

GB: Spent a large slab of my life in small mining towns. The largest was about 20,000. Still small enough to easily walk across.

Problem with these small towns was that they could rarely support a two career family and, if you lost your job, you were unlikely to find another job in the town. Employers tend to be reluctant to interview applicants living in remote areas.

It is also difficult to do contract work somewhere else because transport to and from mining towns is difficult.

Living in a place like Brisbane overcomes many of the employment problems listed above. When we moved to Brisbane there were plenty of opportunities for my wife to pursue her interests and plenty of potential employers for me to approach. It was also a good place to work from in the sense that there was a good air service that allowed me to easily do site work in places as far away as Groote Eylandt, Central Qld, Hunter Valley, Whyalla and Indonesia. Large towns like Mackay may have been better from the Central Qld point of view but much less efficient for any of the other sites mentioned.

All I am saying is that, from an employment point of view, state capitals are a good place to be based.

The growth of internet technology will weaken the link between where you work and where you live. However, for the time being there is a lot driving the growth of our mega cities.

John Davidson:

Thanks a lot for your thoughtful, and helpful, comment.

Single industry towns do present some problems as well as advantages. Lack of job opportunities for spouses, partners and children are one of them; lack of job opportunities if you get into conflict the main employing firm is another.

The best alternatives to megacities seem to be either (a) small towns (several hundred inhabitants) with good transport links and within easy reach of other towns; or (b) regional cities (up to 40 000 people), with multiward hospitals, supermarkets and specialized businesses ,courts, airports and so forth. Both types need diverse industries, cheap housing, inclusive societies and plenty of opportunities to improve one’s life (education, recreation, adventure and the like).

There are much cheaper, much happier and far more efficient alternatives to megacities.

Hi John I am not able to see the graph either on this blog or yours. I am viewing this on my iPhone, don’t have any other way of seeing it at present (on holidays).

It is interesting that Germany has only one largeish city, Berlin (3.5 million, smaller than Melb or Sydney) and many smaller ones, mainly below a million: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cities_in_Germany_by_population

John D.:

There’s one thing that would drive the growth of Australia’s megacities downwards rather rapidly; general war – especially one in which are used weapons of mass destruction (real ones – take your pick). Although the awful recent conflicts in the Middle East killed thousands of city dwellers; urban casualties in a general war would be a few orders-of-magnitude higher. How would a post-war Australia fare with a population of only 7 to 9 million and most of its vital infrastructure in ruins or gone completely?

Val:

Thanks for those stats on Germany; some of them really surprised me.

Val: The graph has disappeared from my screens too. Will try and fix it. It is a useful graph.

GB: We have lived in a number of places for over 8 yrs years each .with populations at the time we lived there of 500 to 1000, 6000, 240,000 and about 2 million. We have enjoyed each of these places and each of them had different things to off.

The isolated township of 500 Alyangula had an intense sense of community where even the village idiot had a place . If we went to an event we would know most of the people there. In Brisbane it is most unusual to know anyone else when we go to a concert. In Alyangula my friendly wife knew all the families. We also knew a wide range of people with a wide range of interests. We did a lot of things at Alyangula because someone there was interested

In Brisbane we know a few of the neighbours well but don’t even know the names of the people in the mansion across the road. On the other hand, Brisbane offers opportunities to mix with people who have similar interests so the range of experiences can actually reduce. It has also allowed both of us to hold positions at state level in organizations we have belonged to. Bit harder to do when living in the serious outback.

One of the things that made the outback towns work was that they were too far from anywhere else so the community was strengthened. We also lived in a mining town that was 200 km Yepoon with a good connecting road. A lot of people from the mining town tended to spend their weekends at the coast instead of in the community. didn’t help.

The city of 250,000 was big enough to have most of the facilities that were available in the state capital while being small enough for me to have a job on the other side of town without worrying about commute times. It was also small enough to get out of at weekends and to still have places nearby where the fishing was good.

The internet is breaking the connection between where you work and where you live. More people will be able to live where they choose to live .

All I can say is that towns of different sizes have different things to offer.

Val: Germany is a relatively recent arrangement made by the bringing together of small states, independent cities etc rather than spreading from a few starting points that were able to hog the growth.

GB: GM says we would have about three weeks worth of transport fuel if imports were cut off. A large part of transport systems, power systems etc. depend on long routes that would be vulnerable to accurate rocket attack. We also live in a world of Just InTime where private knows best My guess is that it would take very little time for a mega city to collapse. None of these silly sieges that lasted for months and months.

John D.

(1) You have mentioned something professional writers on the subject tend to overlook: what might be called the “weekend effect”, the one that has a stifling effect of community cohesion. Overcoming that does take effort, commitment and innovative people – I did see that in one community of less than 8 000, one which did have real community cohesion, weekend or not, despite all the sparkling attractions of a major city just over an hour’s drive away. It can be done – but, gee, it’s not easy.

(2) More like three hours of transport capability left if a general war suddenly hit us. Don’t ask me why, but all the estimates I’ve come across seem to ignore Enemy destruction of Our fuel supplies and distribution systems. If twenty-two or so bridges (not all of them big) get knocked out, we’ll be back to 18th Century – which makes me wonder what they were smoking when Australia bought the U.S. Abrams main battle tank …. duh!

(3) What Australia does lack are unique, specialized towns. Alright, Tambo does produce Tambo Teddy dolls and there are a few towns with a good supply of very individual wineries and also,Tamworth and Gympie do have their music festivals – but we have a long way to go before have we towns renowned for one specialty or another.

The weekend town effect I saw affected a town of about 20,000, most of who were Central Queenslanders most of whom would have had links to the coast. Many of them intended to retire to the coast and got houses there before they retired and the coast was a good place to spend a weekend. (We went there often.) In addition we went to the town after the kids had flown. Kids tend to pull you into what is going on in a town and lots of events are about giving kids things to do.

We saw a weekend effect but larger towns are less cohesive, a Central Qld mono culture is far less vibrant than the multi cultures with not many Australian born that we experienced elsewhere. So don’t take my word for the reason.

All I am really suggesting is that you ask what people do at weekends before deciding to move to a town that looks like what you think of as “the right size.”

Small towns that want to attract lots of visitors can be helped a lot if they are part of a tourist trail.

I’ve inserted John’s graph in the post based on Brisbane traffic to the CBD but similar patterns would apply to other large cities:

Sorry, can’t make the text explaining the icons more legible, but I think you’ll get the idea.

John Davidson (Re: JANUARY 22, 2018 AT 9:48 PM):

I’m only relaying what I see.

At weblog crudeoilpeak.info is this post about Australia’s woeful fuel stock holdings. The critical fuel is diesel: 10 to 20 days in-country stock holdings.

And then recently in The Australian, on Jan 4, Senator-designate Jim Molan is reported to have said:

It doesn’t have to be a war to disrupt Australia’s fuel stocks. It could be really bad weather that disrupts Australia’s major supplying refineries (Singapore, Japan, South Korea), transport ships, etc. It could be fuel contamination. It could be terrorism.

But the Australian Government is effectively saying “don’t worry, she’ll be right”.

The sooner our dependency on petroleum oil is reduced substantially, the less vulnerable our transport systems become.

Geoff M.:

Yes, there are more than wars that can derail a transport system.

Much of supposed need for transport is both irrational and, in the broadest sense, uneconomic – regardless of the mantras of cult-followers pretending to be economists. Apart from the unnecessary costs, our overdependence on transport has made us vulnerable to all sorts of military and economic attacks.

Just a guess:

Under wartime conditions, likely that military needs for diesel etc. would have top priority and requisitioning etc. by armed forces/govt would be in force.

This changes the arithmetic.

It might be I couldn’t drive the family car to the beach for a few weeks or months; no great loss to the family or the economy.

But my impression is, the nation is less well-prepared for war than it is for bushfires, small scale rescues, road smashes, droughts and so forth.

Ambigulous (Re: JANUARY 25, 2018 AT 7:52 AM):

You are correct. But do you think 10-20 days of in-country diesel fuel stocks are an adequate buffer to implement emergency measures? I don’t think it provides an adequate level of resilience for our nation. No diesel means no trucks and rail locomotives.

Indeed. But it could mean much greater restrictions – potentially no fuel at all for private vehicles, depending on how severe the fuel supplies are curtailed and how long the restrictions remain. For those people who live in residences that are many kilometres from shops (for sourcing food supplies) where there is little or no public transport, that could be a big problem for many people. If you don’t grow your own food you may starve. If you can’t get access to your regular pharmaceutical supplies, your health may deteriorate.

And with no fuel available for private vehicles, how do many employees get to work that currently rely on their own transport?

From this article:

And this:

A succession of governments are hoping we remain lucky. That luck may not last.

Some very pertinent points, GeoffM.

Well said.

Geoff M.:

Enemy (that’s us) fuel stocks would be a primary target in any war – which is why I did wonder at Jim Molan’s delightfully optimistic estimate of our actual fuel reserves in a shooting war; given his wealth of operational high-level experience.

Perhaps if he did make a realistic estimate, it would be too shocking for our effete elite to accept; they would slam their minds shut and pretend it couldn’t possibly happen to nice people like themselves – whereas a polite fib might stir them into useful action. Just my guess, anyway. Cheers.

GB/GM: Almost all those who were adults during WWII are either dead of close up. We have largely lost our collective memory of what it was like when Aus was under serious threat. As a result, the private is best mob are allowed to make decisions on the basis of what is best short term for business while ignoring more strategic decisions that might make the country harder to damage during conflict.

A pertinent example is the “where to store” decision. From a strictly business point of view the smart thing to do is to store close to the producer because this minimizes the working capital tied up in stored product. However, if we are thinking about what happens when we run out of the magic three weeks worth of diesel the ultimate consumers will have no way of getting their hands on the stored product. The sensible strategic decision for critical consumables is to store as close as possible to the ultimate consumers.

I agree with GM that three weeks worth of diesel is not enough. However, if all we do is buy more diesel and store it in big, easily targeted tanks at the wharves we will have gained almost nothing. We need to store it closer to key consumers. For example, in smaller tanks spread along the transport routes that we need to keep going when the country is under attack.

The same argument applies to other key needs. This is part of the reason I argue for roof top solar combined with local batteries and inverters that allow houses and businesses to continue using their rooftop power during blackouts.

Graham Bell (Re: JANUARY 25, 2018 AT 7:33 PM):

I think Jim Molan’s estimates of Australia’s fuel reserves are realistic. I don’t think it would be wise for him to understate fuel reserves because then he could be accused of being alarmist. The evidence I see corroborates roughly what Molan is saying – I think he is telling it as it is.

As I said before, war isn’t the only reason for fuel shortages. The Australian Senate inquiry into Australia’s transport energy resilience and sustainability at the Sydney public hearing refers to a fuel “tightness” during 2012. The Committee Hansard for the Sydney public hearing from page 24, includes this:

I think the rest of the exchange is informative.

There just needs to be a confluence of events (worse than in Victoria 2012) that produces “a perfect storm” and Australia’s luck runs out.

John Davidson (Re: JANUARY 25, 2018 AT 10:17 PM):

I think, with a post- ‘peak oil’ world arriving soon, there’s no point in wasting resources building more fuel storage.

We must leave petroleum oil, before oil leaves us. We need to stop consuming oil to mitigate dangerous climate change.

I reiterate what I stated earlier:

That means transitioning to electric (and perhaps hydrogen) vehicles as soon as possible, as well as transitioning our electricity generators to renewables and increasing capacity.

I agree that this helps being more resilient. But large-scale generators are required for energy hungry enterprises like aluminium smelting, etc.

GM:

I was not simply talking about short term fossil transport fuels. There are other critical things like food where our storage policies need to change.

Our long term transport resilience will depend on where we manufacture and store transport energy. It could be biofuels, electro fuels or electricity we are talking about.

I don’t see aluminium as critical we could do without aluminium smelting for a long time before we faced a crisis. Crisis planning needs an understanding re what is really critical and what needs to be done about it.