Most of us would like to be able to travel when, where and how we want to and for the transport system to be managed in such a way that there will always be enough capacity to allow us all these choices. The problem with this “capacity management” approach is that a lot of money would have to be spent providing capacity that is only used for a very limited time of the day. Without this extra spending we still have to continue putting up with congested roads and overloaded public transport during peak hours.

Required capacity could be reduced by managing the “when”, “how” and “where” choices. This post looks at some “demand management” strategies that might be used to reduce peak capacity requirements These strategies offer rapid, low cost ways of getting more from the transport infrastructure we already have. It was concluded that a rapid, low cost doubling of capacity is not an impossible dream.

DETAILS:

Australian mega-cities are all suffering from transport system capacity problems. For too many people, peak hour travel involves very slow driving along congested roads or standing up for long periods in overloaded public transport. Worse still, the overloaded system contributes to long delays if there is an accident or other disruptions to the transport system.

In the past we have tended to respond to increases in peak demand by increasing system capacity to meet this demand. This approach may be OK while there are low cost options available to meet new requirements, however, it is no longer OK if we have got to a point where further increases in capacity will require things like bulldozing buildings to widen roads, adding extra train tracks, digging tunnels and other expensive, brute force options.

Even the old “divert more people to public transport” can reach a point where increasing public transport capacity becomes a lot more expensive than just buying a few more trains and buses. For example, in Sydney, some experts are suggesting that “Sydney trains could be fixed by halving car registration and cutting tolls.”

There is a limit to the capacity of train lines and stations. Building extra train lines and higher capacity stations is never going to be cheap, particularly if the infrastructure can only be installed underground or up in the air. CBD bus stations don’t come cheap either.

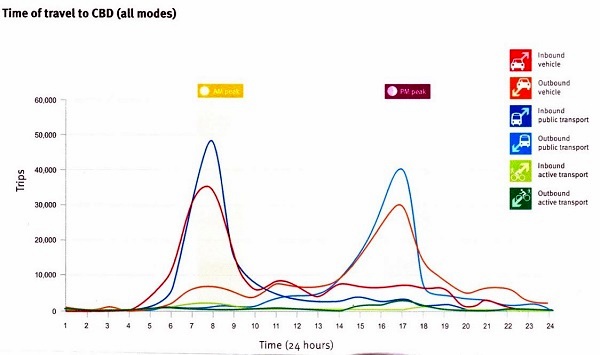

A key part of the problem is that both fixed and mobile transport infrastructure capacity requirements depends on peak demand, not average demand. Fig 1 is a graph of trips vs time of day is based on travel to and from the Brisbane CBD. Similar patterns would apply in other large cities.

Fig 1: Trips vs Time of Day – Brisbane CBD

The graph highlights the extent to which the narrowness of the morning peak contributes to the capacity needed to allow us to travel when we want to. This post looks at two specific strategies for reducing the peaks, “flattening the peaks” and “reducing daily commutes.” In both cases it is assumed, for convenience, that the distribution of travel time and commute method would stay the same. (This does not mean that changing these distributions should not be part of a broader plan for improving transport capacity.)

FLATTENING THE PEAKS

If you look at the fig 1 morning public transport flow into the CBD the peak occurs at about 8 AM with about 50,000 trips into the CBD happening at peak time. In theory, this peak could be reduced by 25% by changing the time when trips occur so that, at no time, the number of trips exceeds 37,500. Some rough estimates based on fig 1 suggest that, to meet this limit, some, but not all public transport commuters who currently travel earlier than the peak would have travel 6 mins earlier than they do now. Those who currently travel later than the peak may have to travel 6 mins later than they do now.

To halve the peak to 25,000 trips the changes to travel time would have to be 18 mins earlier or later.

Similar rough estimates could be made from fig 1 on what changes in travel time would have to be made to reduce peak car travel into the CBD. For the morning car curve a 25% reduction in peak would need start time to be moved by about 9 mins.

It is assumed that time spent at work will not be affected much by the above changes. This means that afternoon peaks will also be reduced if the morning peak is reduced. (They are already lower than the morning peaks.)

NOTE: It is emphasized that the above figures are based on a particular set of figures and may be different for different for other dates and locations. In addition, on some routes, what may need to be controlled is arrivals at some congestion point some way out from the CBD rather than arrivals at the CBD.

How could these changes be achieved?

One of the simpler ways of flattening the peaks would be to change workplace start time distribution to the extent that this is practical. Changing start times does not require significant expenditure into complex controls and could be initiated by convincing some, but not all, employers to change their start time policies.

It should be kept in mind during discussions that there will be different limits on what changes individual employers and employees are willing or able to accept:

- The nature of some businesses means that they will need to continue starting at a specific time. (Think a morning coffee shop.)

- Some businesses will be able to change their start times but will want all their employees to change by the same amount. (Think of many factories.)

- Some businesses will want members of an individual team to start at the same time but would have little problem with different teams deciding to start at different times.

- Some businesses could accept considerable variation in the start times of many of their employees as long as they put in the hours required to get the job done.

- Some employees would be able to do part of their work before or after travelling to/from the workplace. (Think: Planning the day, writing reports, checking emails and making phone calls)

- Some employees will have limits on what changes would be acceptable for personal reasons. (Think: Can’t leave home before they get the kids off to school.)

- Some people will live where they can get to work without contributing to congestion or public transport overload. (Think: People living within walking or e-scooter riding distance from work or those who use routes that are not congested.)

- Some people would choose to travel outside of peak hours if they were able to choose flexi-time.

In some cases it may be practical for individual employers to control individual start times to match the overall start time distribution target. In other cases, achieving the overall distribution target will require co-operation between employers to get the overall mix right.

The above figures suggest that, right now, we could get significant improvements without anyone being forced to change starting time by more than 15 minutes. As the pressure on transport capacity increases the system may have to become more sophisticated and authoritarian. Even then the cost of these changes should be negligible and there will be cost savings due to reduced public transport fleet size, better public transport fleet utilization and the deferral of expenditure on transport infrastructure.

It should be remembered that what is important is the managing of peak hour commutes along routes that suffer from congestion or overloaded public transport systems rather that when people actually work

REDUCING COMMUTES

Reducing weekly commutes and/or average commute distances will help reduce transport emissions and other environmental damage.

Part of the problem with transport in mega cities is that most city workers belong to a group that all work the same old 5 day Monday to Friday commute roster. Both the rosters described below address this problem

5 Day, Monday to Friday COMMUTE Roster

This approach would suit people who need to work Monday to Friday AND Do not need to commute 5 days per week because they can do part of their work at or near to home. (Most people whose ” job involves frequent dealing with other people” could do this from home using phones, emails and Skype equivalents.)

It is not suited to people who are only able to do their work at the workplace.

Key features of a 5 day commute roster might involve:

- Workforce is split into A and B commute crews.

- Crew A may commute during peak travel times Mon, Wed and Fri.

- Crew B may commute during peak travel times Tues and Fri.

- Workers who are not rostered for the days peak commute would either work at home and/or commute outside of peak commute times if they really do need to come into work on that day.

This 5 day commute roster could halve the peak hour commutes of the workers using this roster and would reduce weekly commutes assuming that they would not all come into work on days when they are not rostered for the peak hour commute. In addition, employers would save money because less work space would be required and there may be scope to reduce public transport infrastructure.

7 Day WORK Rosters

7 day rosters provide a way of reducing the daily commutes of people whose job can only be realistically done at the workplace

We could halve the daily commutes of this group by splitting into at least two separate crews that between them work a 7 day Monday to Sunday roster. (Each crew would average 3.5 working days on and 3.5 days off per week.) In addition, 7 day rosters have the potential allow better use to be made equipment and working space. (For example, a factory moving from a 5 to 7 day roster could boost capacity by 40% if the workers worked the same hours per working day or double capacity if the workers increased hours per day to keep weekly hours the same as those worked on the 5 day roster. Even greater gains might be made by recreational businesses that currently depend on weekend business.

There is nothing radical about this 7 day rosters proposal. Many industries work 7 days per week and use multiple crews to cover the 7 days. Some of these rosters are toxic to the workers and their families while others are quite attractive. For example, a number of mines that I worked at in Central Qld had each crew working 4 days on 4 days off. (12 hr shifts.) This was a very popular roster. The mines that had this particular roster had very stable workforces with good morale. The roster gave the workers more days off per week than Mon to Fri while avoiding the long periods away from home that were a feature of some of the more toxic rosters.

Weekend days off is an issue when comparing different 7 day rosters. A 4 on 4 off roster gives, over a 7 week cycle, two full weekends off plus two other weekends where the crew members had either Sat or Sun off. Other rosters could give different patterns of weekend time off. For example a 7 on, 7 off roster could be arranged so that the crews always had Sat or Sun off every weekend.

Simply splitting the original single crew into A and B crews does have a number of disadvantages:

- There is no overlap when both crews are at work (Bad for work communication.)

- The only time the crews will have time off together is when they are on holidays or on strike. (Not good if family members are in different crews and not good for communities.)

The above problems with two crew systems can be reduced by setting up a 4 crew system where:

- A and B crew alternate.

- C and D crew alternate with C crew starting at least one day after A. This overlapping means that there is at least indirect communication between all crews and that a person working A or B crew will also share time off with C and D. (Gives a better chance of family members sharing time off and better communication within the community.)

The family and community problems will also be reduced if different employers use different rosters or simply start roster cycles on different days. This will increase the number of people who share some rostered days off. To reduce confusion it is important that “A” crew describes crews that are rostered on and off on the same days.

Small businesses and teams may decide being part of a roster is attractive while choosing to all work in the same crew.

My personal preference would be 4 on 4 off with 4 crews and with C crew lagging 2 days behind A crew. However, it is all personal and we play for hours developing rosters that have particular attractions.

It would not take long to move at least some people and employers to 7 day rosters. Costs and benefits would depend on what if any increases in wages are involved and the potential savings and increased sales for employers.

CONCLUSION:

Australian mega cities have already reached a point where the transport system cannot cope with the expectation that the system must have the capacity for people to travel when they want to, how they want to and where they want to.

This post demonstrates that some forms of transport demand management have the potential to dramatically increase the capacity of the existing system without spending a lot of money or having to wait for years for any significant benefits to be felt. In some cases there will be genuine reasons why specific employers or employees should not be expected to do some of the things suggested but the transport crisis has reached a point where there must be a very good reason why start times should not be adjusted to reduce peak transport demand or serious consideration be given to other strategies that will reduce peak demand.

Perhaps employers should be asked what they are going to do to reduce the number of their employees and contractors who contribute to peak demand.

Rapid, low cost doubling of transport capacity is not an impossible dream with either of the strategies suggested.

John, flexi-time was introduced in the public service, from memory, back in the early 1980s. There was talk then about varying work times more broadly. Nothing happened.

Could the problem be that no-one is in charge? Presumably the state government could do it.

Brian: I remember someone commenting in scathing terms about flexi time and a senior CSIRO scientist we worked with. At the time I thought it was a good idea and subsequently enjoyed a degree of flexibility in many of the roles I worked in. Not unreasonable in that departure time tended to be substantially later than arrival time was.

There was never any talk of helping transport although avoiding the peak rush was a key reason I liked to start late at Thiess.

Yes, Brian

I recall that vogue for “flexi-time” in the 80s and 90s.

Some managers hated it: they lost their ability to ‘snap fingers’ and call a subordinate in to chat.

Most places I heard of, had a core time period, say 11.00am to 2pm, during which all F/T employes had to be there. Thus meetings involving lots of staff would be scheduled during that core time. Arriving at 10.30am or leaving at 2.30pm would mean travelling outside the peak?

I heard of a case in 90s where a staff member turned up about an hour early, Monday to Friday, because that way they avoided traffic jams in the morning. Boss still expected them to stay late. That way, afternoon congestion was avoided. But parking fees were very costly. Public transport didn’t cut the mustard for that person.

A few years ago, Metro trains in Melbourne had free travel in the very early morning, for folk going into the CBD. Not sure how long the experiment lasted.

More white collar folk “working from home” may be a small factor lowering commuter numbers.

Seniors concession cards often specify train, tram, bus travel must be “off peak” or weekends.

At a personal level flexi time worked for people like me as long as you didn’t have a boss addicted to long late afternoon meetings. On the other hand most of the people who worked for me needed to start at fixed times because of the nature of their work and the fact that they were part of a team who all needed to be there at the same time for shift changes, start of shutdowns etc.

Having said this, there was no reason why the mining and concentrator shift crews could not have had different shift crew swap times if there had been some benefit in making this change.

When I started work at the Newcastle steelworks the workforce was split into morning start times of 7.30, 8.00 and 9.00. The steelworks was such a large employer that the 3 different times would have reduced congestion transport peaks as well as reduced crowding in the change rooms.

Yes John

Particular workplaces often have special requirements, but your Newcastle steel example illustrates how a few large employers can be influentual.

I have rewritten the conclusion to give the post a bit more bite. The changed conclusion says:

Hope you like the change.

John, change looks good. I was surprised at how much benefit could be obtained from a fairly small variation of times.

Ambi, from memory, in the public service core times were 10-12 and 2-4 unless you had the half-day or day off. I think days off were limited to one every fortnight and may have only been Friday, so that you could schedule staff meetings etc.

With daylight saving as well it was difficult to contact people interstate.

Brian: The demand management message is finally getting home in the power industry but the same needs to happen for transport.

Thanks Brian

In some white collar workplaces the “lunch hour” lasted only 30 or 40 minutes. As a pleasant, useful period in the working day, it definitely needed to be in the middle of the core time, for better morale.

Brian/Ambi:

Any feel for how much flexi time reduced peak hour commutes and what job classifications actually used it?

Numbers would have been quite low I think. Melbourne CBD State Govt white collar staff, probably outer suburban State, Federal govt funded persons, e.g. CSIRO.

My guess is that more recent “working at home ” or flexible part time work might be having a bigger effect, but still minor in the overall picture.

Are some tradies and (e.g.) gardeners, lawn mowing persons, handymen etc. more able to avoid peak traffic times by their job scheduling?

Ambi: I would have guessed that flexi didn’t have much effect. It is going to take a lot more insisting to use demand management to solve transport problems. It is also going to need different options that suit for different groups of people, many of whom cant get their jobs done using flexi time.

I have added this extra section called “Other Rosters” to cover jobs that are not really suited to working 7 day rosters:

OTHER ROSTERS

It should be emphasized that what is important from a transport point of view is managing peak hour commutes along routes that suffer from congestion or overloaded public transport sytems rather that when people actually work.

For people like many factory workers who need to start and finish as a team 7 day rosters are a sensible way to do it and come with other financial and recreational benefits that workers and employers may find attractive. (This doesn’t mean that there are not benefits to be had from changes in team start times.)

7 day rosters as described above can be a problem for people whose job involves frequent dealing with other people who work Monday to Friday. For these people it may make sense to set up a “Commute roster that operates Mon to Fri.” For example:

Workforce is split into A and B commute crews.

Crew A commutes during peak commute times Mon, Wed and Fri.

Crew B commutes during peak commute times Mon, Wed and Fri.

Workers who are not rostered for the days peak commute would either work at home or commute outside of peak commute times if they really do need to come into work. Most people whose ” job involves frequent dealing with other people” could do this from home using phones, emails and Skype equivalents.

Made some more changes to make the post easier to understand and take account of some of the comments made.

Hardly surprising, this report claims that flexible working hours aren’t great for all. The report talks about things like replacing 5x8hr week with 4x10hr weeks.

Further reading suggests that part of the problem was that the hours were dictated by the employer, not the employees, not all jobs suited 10 hr days and there needs to be core times/days when all employees will be available for meetings and other activities that require people to work together.

My own experience was that max hours of effective work depended on the nature of the job. For example, I could handle 12 hr shifts when working as a shift commissioning operator while working more than 8 hrs per day on detailed design simply meant that most of the extra hours were spent fixing the mistakes made because I was working too many hrs per day.

In general shorter hrs are needed for detailed and creative work.

My personal preference is to be paid by the hour and have some flexibility with the hrs worked per week.

John, I think the observation about how long you can usefully work on various tasks is an important observation. I heard one bloke, in mining, I think, saying 4 x 12 hours followed by 4 days off suited him.

I also heard someone concerned with transport saying that when driving a truck a half hour break after 5 hours driving was mandatory.

Some workers would be willing to do 10 or 12 hour shifts although they would be unproductive a fair bit of the time, which wouldn’t suit the employer.

So there are complexities, and a question as to where there should be rules that protect the public interest. I believe in the US that when the fire truck comes you should assume that the workers are working two jobs, which isn’t good.

Brian: 12 hr shifts have been common in some of the washeries and concentrators I have worked in. I have often worked 12 hr shifts (usually night shift) as an operator during commissioning without too much of a problem as long as creative work was not required I can certainly think of times when we did things the hard way when I was too tired and realized after a days sleep that it would have been a lot smarter another way. There was also a safe driving issue when going back to camp after a 12 hrs night shift. (In addition to other tiredness safety issue.)

I have also been at sites where the project team was working ridiculous hours. What I really noticed was that when a problem came up the team would shuffle around until one potential solution came up and then narrow in on this solution and ignore other possibilities until the initial “solution” had been proved not to work. (Which often took days when equipment had to be sent to site.) A more wide awake team would have would have come up with a number of potential solutions and, where appropriate pursued a number of solutions where this was appropriate. The problem was made worse by a tendency for “able to work long hours” became a macho thing.

In the end I started insisting on a 10 hr daily limit for commissioning work.

I do think that 4×12 hr shifts in a row would have been much better than 6×12 hr shifts a week.