There is a new economic blockbuster out, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War by Robert J. Gordon. In brief, his thesis is that 1870 to 1970 was a ‘special century’ of technological change yielding dynamic economic growth that transformed our lives. By contrast in America, nothing much has changed since then, growth has tapered right off and there is little prospect of significant change.

Is he right? Paul Krugman says, “My answer is a definite maybe.”

Robert Samuelson gives another account of Gordon’s argument. For him it is too early to say whether Gordon is right. Gordon, he says, does not reject the promise of technology but rather gives a sobering reminder of its limits. Gordon also limits his argument to the private sector. Samuelson says it’s in the public sector, where fields like education and health represent a quarter of the economy, that fail to improve their productivity.

Martin Ford broadly agrees with Gordon about the past, but not about the future. Innovation, he says, has actually accelerated. While not as spectacular as electricity and the internal combustion engine, it is all pervasive:

- information technology (and specifically artificial intelligence) is going to intertwine with any innovations that occur in the future and make everything less labor intensive.

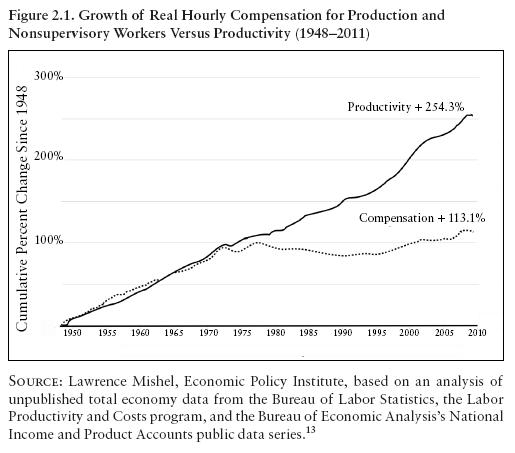

But unless we change the economic rules growth will be snaffled by the few at the top, as it has been in recent decades. Ford posts this interesting graph of real hourly compensation for production and non-supervisory workers versus productivity:

Gordon’s piece at Bloomberg reads like a response to his critics, but it’s actually an excerpt form the book. Contra Ford’s graph he says that there was a lift in productivity for a while from the mid-1990s but it has petered out since:

- Labor productivity, far from exploding as machines and software replace people, has been in the doldrums, rising only 0.3 percent a year in the five years ending in mid-2015, in contrast to the 2.3 percent a year in the dot-com period.

He agrees about steady middle level jobs disappearing and sees inequality as a real challenge.

- Slower productivity growth and low-wage jobs are leading to the unequal distribution of productivity gains. Those are the real headwinds that America faces.

Just backing up, from Krugman, Gordon says five Great Inventions powered economic growth from 1870 to 1970:

- electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine and modern communication.

Modern communication includes the telegraph and telephone, radio, film, television and the beginning of computers.

As far as I can tell, he doesn’t look at agriculture. In premodern times around 95% of Europe’s population were growing food. J. Bradford DeLong tells us:

- In the US, roughly 1% of the labor force is able to grow enough food to supply the entire population with sufficient calories and essential nutrients, which are transported and distributed by another 1% of the labor force. That does not account for the entire food industry, of course. But most of what is being done by the remaining 14% of the labor force dedicated to delivering food to our mouths involves making what we eat tastier or more convenient – jobs that are more about entertainment or art than about necessity.

Which raises the issue service industries. Tourism, for example, exploded in Europe from about 1960, when the population at large became wealthy enough to take trips away.

Finally, we have to remember that all these people are talking about America. For a quick snapshot here, have a look at this piece from the Courier Mail, which highlights then and now 48 years ago, when our population was half the size. (Thanks to John D for the link.) Get a look at this:

- 12. The male average hourly wage was $1.22 and the weekly full time wage was $48.93 which in today’s dollars is $567. The current average weekly full time earnings is almost three times this at $1,484.50.

Before we get too excited, remember this:

- 18. Homes cost five times more. The median Sydney house price was around $18,000 (in today’s dollars this equates to $195,300) compared to the current Sydney median house price which exceeds $1 million.

I liked the two postal deliveries per day back then.

But Gordon would say we had cars, electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, the phone and much else. Unless you lived in Brisbane you probably had an indoor loo.

I tend to think that changes like 3D printing, nanotechnology, genetic manipulation, driverless cars, universal digital connectedness, the whole human-technology interface (that’s just off the top of my head) will amount to something significant.

However, there’s something else going on. At the end of this article, which does my head in a bit, we are told:

- After all, globally, standards of living are continuously improving and converging. (Emphasis added)

Seems for real incomes growth we’ll have to wait for the Indians and Chinese to catch up.

If Mason and Gordon are concerned about growing inequity and Mason thinks the economic rules need changing, they might consider the ‘Nordic model’ (thankyou zoot!) It’s about civilising capitalism.

Like some others who come to this site, I can remember the exceptionally high standard of living we enjoyed in the “Fifties and early ‘Sixties – despite our overseas trade being tied to Britain’s apron-strings, despite local firms being stifled by the Americans and their anti-competitive trickery, despite appallingly bad management and union practices, despite Menzies clinging to power by giving away our birthright.

It was an age when housing really was affordable because it was appropriate to the actual needs of the occupants. There was purposeful work for all who would seek it, and although wages were comparatively much lower, the spending power of those wages was much better.

There were many, many problems in those days: like the cultural cringe which hindered local innovation in social justice , in education, in military and diplomatic affairs, in so many other fields – and this cultural cringe persists and is worse now.

Best of all, there was hope for a good future.

Where did we go wrong? We didn’t sack Menzies as soon as the effects of his playing Santa Claus with our taxes became obvious in the Credit Squeeze of 1958. We didn’t stand up for ourselves when 6 senior public servants were brought to the bar of our Parliament, in July. 1975, and they reversed the employer-employee relationship on us (which has had a far worse and more enduring effect than did the Whitlam Sacking in November that year). We didn’t riot when Hawke opened up Australia for plunder in the name of economic reform.

What can we do to restore our former high standard of living, at least, in part? We could start by boycotting the foreign-controlled businesses. Do you really need a new wall-to-wall TV – or an eleventh pair of shoes – or horribly expensive, low nutrition “festival food” at every meal – or a subscription to an expensive non-service – or coloured beads, blunt axes, thin blankets and bottles of fire-water (as did the native peoples in previous excursions into rapacious trade)?

Putting a padlock on our purses and wallets will hurt – but it would force us to work towards improving our own standard of living instead of continuing to improve the hoard of the 62 richest men on the planet.

All of my working life I would have happily traded more holidays for a corresponding cut in wages. (One week = 2% wage cut.)

The point I am making is that economies should flatten out as more and more people are paid enough to want to start trading off working hours in return for wage cuts.

Think about it:

1. We need an aggressive advertising industry to keep the demand growth required t keep the economy growing.

2. We need junk that doesn’t last very long to stop the economy declining.

3. Wages have had to grow to prop up the speculative growth in house prices.

Problem is that we don’t have a worksharing system that breaks the link between economic growth and employment.

The world and many lives would be better if we found a fair way of reducing production and consumption.

John, my wife did work-sharing with a friend while a teacher. There are problems, in compatibility of teaching styles, messages being passed about important stuff brought up at staff meetings, communication with parents etc. Many principals don’t like it because of that.

In the ‘Nordic model’ link the claim is made that a full-time salaried worker in Norway averages 37 hour per week, whereas in the US it’s 49. I used to average about 60, hence 23 hours per week unpaid overtime. Culturally in Scandinavia a decent work-life balance seems to be valued.

What could help a country maintain a high standard of living ?

How about exports ?

Australia export tree.

Norway export tree.

Jumpy, take a look at Sweden and Denmark, the others in the Nordic model.

Then consider Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the biggest in the world, in which they’ve captured the benefits of their resources bonanza for future generations. Basically, we pissed it up against the wall.

In Scandinavia it largely depends upon sharing the wealth, and I already know you disagree with that.

The unpalatable (for you) fact is it works.

John

There is a system ( probably illegal ) kicking around the Tradies at the moment. More of an informal agreement really.

It’s just hours banking.

In the busy times, anything over, say 36 hours ( negotiable of course ) is banked and payed out when work is slack.

No-one is obligated and only core staff have the opportunity depending on their own individual wants.

The steady financial flow for both and helps avoid mass hiring/mass sacking seesaw.

Some features of “work choices” were actually quite good for employees in certain industries and smaller employers.

Ok then, Norway and their massively fossil fuel dependent economy is just fine and dandy on Climate Plus because they’re socialists, got it.

What next, Venezuela ?

Jumpy, elsewhere you said two of them were dependent on fossil fuels. As far as I can see only Norway is to a significant degree.

Of course I’m not happy about the fossil fuels, but I still need fuel for my ute. I’m not happy about that either, nor about Queensland’s dependence on coal and coal seam gas.

However, I’m betting the Norwegians are smart enough to adapt to a post-fossil fuel era. Our politicians and major industry leaders are distinctly second rate. That’s at least as big a problem as ideological orientation.

John D: You’ve summed it up elegantly! So then we would have more satisfaction for less effort, less waste and less damage.

Like witch-burning, never-ending growth has failed to make us better off, happier or safer. The Age of Consolidation is here – so let’s take full advantage of it.

Jumpy: That the Norwegians based their sovereign wealth fund on hydrocarbons rather than, say, fishing or timber or lace-making is less important than the fact that they have a sovereign wealth fund at all. We have the opposite here in Soviet Australia: open slather for the Commissars-in -business-suits to plunder our resources and to hell with the proletariat – while we allow that ruinous situation to persist, we will never ever have a sovereign wealth fund ourselves to protect our standard of living nor the funds to exploit great new opportunities..

The evening out of wages and hours, “banking it”, is a good idea but one that can only work if there is an exceptionally high level of trust between employer and employee.

Brian: Thanks for mentioning some of the real-life problems with job-sharing: once a problem is noticed it is part-way to being solved.

As for the long hours, lower pay, fewer benefits and short holidays about which Americans boast: lower productivity per worker is what they don’t boast about. Not quite up to the old Soviet joke, “They pretend to pay us – so we pretend to work”, but getting there …. and, of course, we tag along behind them as usual.

Brian

60% of Denmarks Crude comes from Norway.Nigerian Crude at 25% is a surprise to me.

Graham, we do have a SWF.

It’s tricky because, constitutionally, the minerals are owned by the citizens on the States.

Therefore the responsibility for such funds, on the back of mining, falls at the feet of State Governments.

So now we have to put dates on the booms or the lead up to the last, say, 3 of them.

Then we can blame the State Government in charge.

For ease let’s go the 2 biggest in terms of mining , Qld and WA.

So, the booms, when do you put them at ?

Lastly, a comparison of SWFs in Norway and here for Treasury by Phil Garton and Dr David Gruen in 2012.

Interesting stuff.

http://www.treasury.gov.au/PublicationsAndMedia/Speeches/2012/The-role-of-sovereign-wealth-funds-in-managing-resource-booms

Heh, I didn’t really mean ” lastly”.

A disincentive to such a State fund would be the GST calve up rules, good performers and managers get punished, basket cases get rewarded.

Great link to Treasury paper, Jumpy, and a decent point about the role of the states.

Can’t see the relevance of where Denmark gets its oil unless it’s getting mates rates.

As an aside, it’s heartwarming to see Jumpy so concerned about fossil fuels.

Thanks Jumpy. I thought the FutureFund was supposed to be just smoke-and-mirrors with only “Monopoly” money in it. Is it real, then?

Beautiful article. Although there was an admission that the effects of investing was not included, there was no admission that the herd of elephants stampeding around the room were not included either – and among that herd are is the foreign ownership of Australian assets or the right to exploit those assets; the giveaways laughingly called royalties (as though offshore investment would flee Australia if somebody had had the guts to negotiate decent royalties for us); the cult thinking that regards government investment as a mortal sin and completely against the natural order of things; the risk-averse nature of Australian “business(??)” and its congenital inability to look beyond the next financial year. Pretty graphs though.

Ooops. Sorry Jumpy. that should have been “…. the effects of investing off-shore was not included”.