Well strictly speaking Neanderthals are humans too, so for “humans” read Homo Sapiens, that is us.

I intended to write a post on taxation policy, but then I heard Phillip Adams’ segment Dogs: not the Neanderthals best friend, an interview with retired anthropologist Pat Shipman on her hypothesis that the domestication wolf-dogs gave us the critical edge to out-compete the Neanderthals. It reminded me of an article by Shipman in the New Scientist. If that’s paywalled there is an excellent exposition of her ideas by Steve Donoghue at Open Letters Monthly.

Anyway Sapiens vs Neanderthalensis won out over tax policy.

Shipman uses the example of Yellowstone National Park to demonstrate the effect a top predator can have on a whole ecosystem.

Though wolves were integral to that ecosystem for millennia, they were wiped out there by settlers by about 1920. The effects of removing the wolf were striking. Coyotes formed larger, more wolf-like packs, while elk populations soared, changing the vegetation close to rivers by eating young trees and shrubs. Pronghorn antelope populations dropped as more coyotes preyed on their offspring; beavers disappeared from the park and songbirds declined in number.

Then:

Reintroducing just 31 wolves in the mid-1950s transformed the ecosystem again. Wolves targeted their closest competitor, killing coyotes in confrontations over carcasses and consuming enough prey to hinder their survival. Coyotes avoided areas favoured by wolves and shifted to smaller prey. Coyote packs fragmented and their overall population declined sharply. More pronghorns survived; elk herds diminished; and riverine vegetation came back, encouraging the return of beavers and songbirds.

Neanderthals survived for about 250,000 years in an environment that presented challenges. Donoghue describes it thus:

Their populations had endured sweeping climate changes over the centuries, and they shared their landscape with animals as monstrous as anything the world had seen since the dinosaurs: massive cave bears, saber-toothed tigers, lions bigger than any in Africa today, cave hyenas, huge woolly mammoths, woolly rhinoceri, wolves, leopards, roving packs of dholes – a world as fearsome and strange as something out of a science fiction novel.

A few thousand years after Sapiens arrived some 45,000 years ago, apart from wolves all these large animals were gone, and the Neanderthals with them.

Shipman says that the common belief was that the Neanderthals moved south to avoid the advancing ice, and lingered until 27,000 years ago. However, she says that modern dating technology shows no southward movement and no trace of Neanderthals after 39,000 years ago.

Sapiens had two big advantages. One was projectile technology to enable killing at a distance. The other was possibly the assistance of the domesticated wolf-dog. Dogs assisted Sapiens in hunting and acted as guards.

It seems likely that Sapiens did not tolerate the presence of Neanderthals in ‘their’ territory. It seems likely also that with projectile weapons Sapiens would win any direct confrontation. If the Neanderthals crept up at night, the dogs would likely smell them and sound the alarm.

The effect of dogs was to increase the ecological niche in which Sapiens could operate. For the Neanderthals there was simply no good place to go, so they were squeezed into areas where they could not support themselves in the longer term. In this, climate change was still certainly a factor.

Shipman says we are “natural invaders, the mammalian equivalent of Burmese pythons, cane toads and Asian carp.”

Shipman stresses that her hypothesis “still requires elaboration and testing.” Nevertheless it is certainly food for thought.

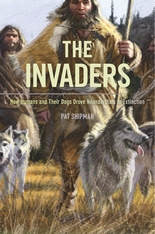

Shipman’s book on the topic is The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction.

You might also be interested in Neanderthals r us and Sex with Neanderthals was good for us from 2011. Seems like yesterday.

Prey competes with prey, predators with predators.

In the case of predators the competition may be direct in the form of wolves killing coyote or lions killing cheetah cubs. Or it may be indirect, in the form of one predator being a more efficient hunter of a shared prey or in the form of one predator being able to hunt a prey that the other predator could not hunt. (Both coyote and wolves could take pronghorn young but both would have struggled to take adult pronghorns because pronghorn are so fast. More to the point, wolves can also take elk while coyote can’t.)

Efficient hunters or hunters that can survive on a more diverse mix of prey are more likely to be able to survive during tough times and/or with lower prey densities.

If we are thinking about modern humans vs Neanderthals, moderns with projectile weapons are more likely to win fights and less likely to be hurt badly even though we suspect the Neanderthals would have been formidable in close up conflict. Projectile weapons would also have made it easier to hunt nervous prey and made it safer to hint mega prey.

Dogs may have helped as suggested but, to my mind, they are not an essential part of the explanation for the decline of Neatheraderals. (Disease may also been a contributor.)