Farming is now worse for climate than deforestation writes John Upton at Climate Central.

And the finger points at red meat.

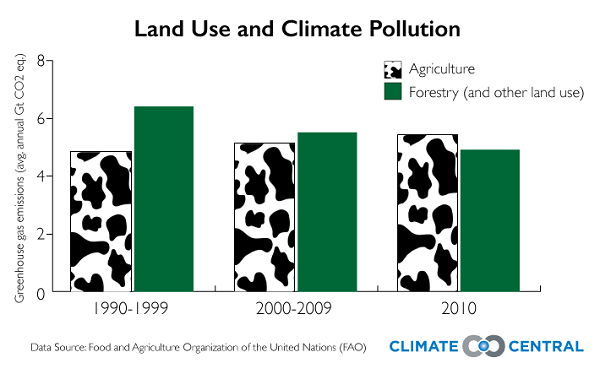

A new study reported on by Upton says that burning fuel produces about four times more climate pollution every year than land use. Nevertheless land use remains an important consideration. Within land use, climate pollution from deforestation has declined over the last decade or two, while agriculture is increasing:

Greenhouse gases released by farming, such as methane from livestock and rice paddies, and nitrous oxides from fertilizers and other soil treatments rose 13 percent after 1990, the study concluded.

Within agriculture, ruminants produce two thirds of the pollution, with cows and buffalo the worst offenders.

Climate talks have focussed on deforestation. REDD (Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) has been a major focus of UN climate negotiations, whereas agriculture has been neglected.

Some countries, particularly India, have been averse to discussing agricultural impacts during U.N. climate negotiations — largely because they fear that the outcomes of such talks could reduce agricultural output and worsen food shortages. “Poor countries are not going to sit idly by and just impose reductions in food production to meet greenhouse gas reduction targets,” Schwartzman said.

Doug Boucher, the director of climate research at the Union of Concerned Scientists, says agriculture’s climate impacts could be reduced without taking food off tables. Reducing the overuse of fertilizers, protecting the organic content of soils by changing farming practices, and keeping rice paddies flooded for fewer weeks every season could all contribute to a climate solution, he said.

The biggest opportunities for reforming agriculture’s climate impacts can sometimes be found miles from where any food is grown. Reducing waste where food is sold, prepared, eaten and, in many cases, partly tossed in the trash as uneaten leftovers or unsellable produce, reduces the amount of land, fertilizer and equipment needed to feed everybody. “Shifting consumption toward less beef and more chicken, and reducing waste of meat in particular, are what seem to have the biggest potential,” Boucher said.

Vegetarianism was not mentioned in the article.

Wikipedia tells us that there are more than 3.5 billion ruminants on the planet, with cattle, sheep, and goats accounting for about 95% of the total population.

Linda Geddes took a look at the merits or otherwise of eating meat in the New Scientist. If paywalled the article is available here.

From the 1970s eating meat was linked with colorectal cancer on a population basis. Countries which ate more meat suffered more.

In 2007 the World Cancer Research Fund pulled together the results of 14 studies, concluding that red and processed meats were “convincing causes of colorectal cancer”. Their report suggested cutting out processed meat altogether and eating no more than 500 grams of red meat per week.

Now this:

Two large studies published in 2012 found that the risk of dying from all causes – including bowel cancer and heart disease – during the study follow-up period was 13 per cent higher for people eating 85 grams of red meat per day, and 20 per cent for those eating 85 grams of processed meat. That would translate to roughly a year off life expectancy for a 40-year-old man who eats a burger a day.

As often in health research, just when all that seemed clear complications set in. Such studies are based on self-reporting as to quantity and frequency and often didn’t discriminate between types of meat or tease out links with other life-style factors. In 2013 a European study:

followed half a million people in 10 European countries over 12 years, and as well as distinguishing between consumption of red meat, white meat and processed meat, it also controlled for factors such as smoking, fitness, body mass index and education levels, all of which might be correlated with high meat consumption.

The study found no association at all between fresh red meat and ill health, but the link with processed meat remained. It found that for every 50 grams of processed meat people consumed each day, their risk of early death from all causes increased by 18 per cent.

An American study of 18,000 people found no association between deaths from cancer or cardiovascular disease and the consumption of meat, even processed kinds, but was criticised for the crudeness of its questionnaire.

Further studies have now linked haem, the component that makes red meat red, with the generation of cancer cells.

Meat, however, remains a handy nutritional package, difficult but not impossible to replace. There is this caution about vegetarianism from the European study:

Perhaps the most surprising finding from the EPIC study was that those who ate no meat at all had a higher risk of early death from any cause than those who ate a small amount of red meat.

Vegetarians don’t always make healthy food choices.

The cautionary position seems to be that small amounts of meat are good – about 70 grams per day. (This does seem very cautious in the light of the European study.) It’s not clear whether it’s best to eat a small portion each day or save your allocation for a splurge. It does matter how you prepare meat and what you eat with it. Avoid chargrilling, eat plenty of fibre and for some reason let the cooked potatoes grow cold! Best to avoid processed meat if possible.

At the production end, there is masses of grazing land in the world that can’t be cropped. The methane, however, remains a problem, which can be mitigated in various ways. That, however, is another story.

It is important to keep in mind that the methane from ruminants, rice going etc. is part of a natural cycle that converts methane to CO2 which eventually ends up in cattle feed, rice etc. Sure, reducing the annual output of methane should give a reduction in the methane/CO2 held in this cycle but the thing we should be concentrating on is keeping fossil carbon in the ground.

If we are talking about a fairer world the land, water etc resources aren’t there to feed everyone on a typical Australian diet. To me this is one of the reasons why we should be talking about radical changes to what we eat and the economics of supplying food.

John, methane emissions from ruminants, rice paddies etc, are in their first year 100 times more potent than CO2 in greenhouse effect. Over 100 years the CH4 converts to CO2 and water. The residual is 20 odd per cent more CO2 in the atmosphere. 3.5 billion domestic ruminants vs 75 million wild ruminants are not part of the natural cycle.

There is one scientist who thinks that ancient rice paddies in China and elsewhere kept the Holocene warm and prevented it from sinking back into an ice age. I understand that the effect is real, but the numbers probably were not significant enough to do the job.

Modern agriculture, I think, accounts for high single figures in our emissions. They are not large overall but an intractable portion if we are trying for zero emissions.

Brian,

The ruminant methane cycle is a natural cycle in the sense that it all goes round and round and doesn’t move fossil carbon into the atmosphere. Having said that our environment would be better off if we used things like kangaroo meat instead of running cattle. (And applaud governments that get rid of wetlands?)

Put it another way. Going on about ruminants is a distraction from what we really need to be doing: Rapidly driving down the extraction of fossil carbon.

John the carbon in the methane emitted by ruminants may be sourced from the atmosphere, but in each cycle the greenhouse effect is boosted when it is in the methane phase. I think the climate models rate it according to its state after 100 years which is a mistake.

As to distractions, I think we need to walk and chew gum at the same time. The whole ‘Kyoto six’ GHGs need to be dealt with.

Right now we have 400 ppm of CO2, while CO equivalence counting all GHGs is 480 ppm. I don’t think climate scientists pay enough attention to this. The problem is 20% bigger than it looks.

When Hansen says we need 350 ppm he also says, that’s assuming other GHGs are net zero.

Agriculture with methane and nitrous oxide from fertilisers deserves attention.

Fugitive methane emissions from shale gas in the US are also thought to be of sufficient size as to nix the advantage of gas over coal, yet I gather they are not accurately counted officially.

Brian: The problem with being told to walk and chew gum is that it encourages people to give in and do nothing because you have convinced them that the job is too hard and that they are stuffed anyway.

By contrast, breaking things down and doing some easy/priority things first is a well recognized way of actually getting things done.

the transition to clean power seems both easier and higher priority than burping cattle and bubbling rice fields.

John, IMO we need a wide spectrum multi-faceted program if we are to get to zero emissions by about 2030.

I agree about the priority that should be given to the transition to clean power, and that’s where the public focus should be. No-one needs to be distracted by ruminants. We need some research on genetics and different types of animal foods or additives. I’m sure there is some going on. If memory serves the Kiwis are looking into it wrt sheep.

The people doing such research would not be working on clean energy if they weren’t doing it.

We need something other than people preaching at us to eat no meat at all, or just eat pork and chicken. My elder brother who produces beef gets the impression that the greens want to run him off the land.

Brian: As far as I know, there is no official Greens policy about shutting your brother’s beef business down. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t some Greens that really want compulsory vegetarianism.

People like me who argue that eating kangaroo is better for health and the environment aren’t mainstream Greens either. (Ban the hoof in Aus!!!)

My economic take is that Australian farmers would lead better lives if they concentrated on products that can go through a good life cycle on the basis of one good rainfall. In the case of animals we should be looking at species that can breed up rapidly after a drought breaks and produce marketable animals before the next one starts. My only problem is that I keep thinking of rabbits as the ideal crop if only they wouldn’t hide in burrows.

Horses, yum !

Yes, in principle something like rabbits would be good.

The greens my bro was complaining about were either greenies at stakeholder meeting or public servants with a very green and farmer-unfriendly ideology. Not The Greens as such, which are thin on the ground where he hangs out.

Brian.

Sorta like radicalised, disaffected, lone wolf Greens rather than moderate Greens from the party of Peace ?

KN: Or sane, rational Greens like me?

KN, I don’t know about lone wolves. The Wilderness Society, for example, is a considerable organisation, with a healthy funding base:

Bout half the average Bunnings Warehouse turnover then, good for them.

And tax free, even better.

Oh, Bunnings doesn’t sell cows either, so, good for them too.