Farming is now worse for climate than deforestation writes John Upton at Climate Central.

And the finger points at red meat.

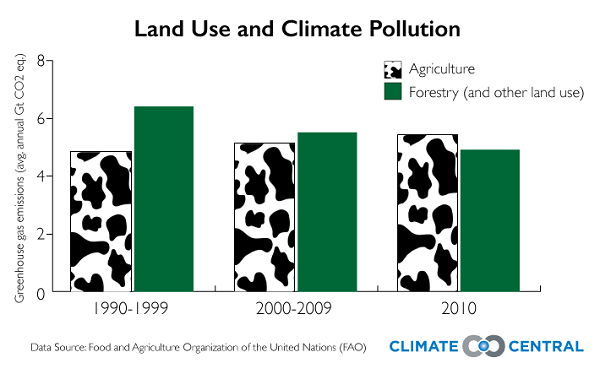

A new study reported on by Upton says that burning fuel produces about four times more climate pollution every year than land use. Nevertheless land use remains an important consideration. Within land use, climate pollution from deforestation has declined over the last decade or two, while agriculture is increasing:

Greenhouse gases released by farming, such as methane from livestock and rice paddies, and nitrous oxides from fertilizers and other soil treatments rose 13 percent after 1990, the study concluded.

Within agriculture, ruminants produce two thirds of the pollution, with cows and buffalo the worst offenders.

Climate talks have focussed on deforestation. REDD (Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) has been a major focus of UN climate negotiations, whereas agriculture has been neglected.

Some countries, particularly India, have been averse to discussing agricultural impacts during U.N. climate negotiations — largely because they fear that the outcomes of such talks could reduce agricultural output and worsen food shortages. “Poor countries are not going to sit idly by and just impose reductions in food production to meet greenhouse gas reduction targets,” Schwartzman said.

Doug Boucher, the director of climate research at the Union of Concerned Scientists, says agriculture’s climate impacts could be reduced without taking food off tables. Reducing the overuse of fertilizers, protecting the organic content of soils by changing farming practices, and keeping rice paddies flooded for fewer weeks every season could all contribute to a climate solution, he said.

The biggest opportunities for reforming agriculture’s climate impacts can sometimes be found miles from where any food is grown. Reducing waste where food is sold, prepared, eaten and, in many cases, partly tossed in the trash as uneaten leftovers or unsellable produce, reduces the amount of land, fertilizer and equipment needed to feed everybody. “Shifting consumption toward less beef and more chicken, and reducing waste of meat in particular, are what seem to have the biggest potential,” Boucher said.

Vegetarianism was not mentioned in the article.

Wikipedia tells us that there are more than 3.5 billion ruminants on the planet, with cattle, sheep, and goats accounting for about 95% of the total population.

Linda Geddes took a look at the merits or otherwise of eating meat in the New Scientist. If paywalled the article is available here.

From the 1970s eating meat was linked with colorectal cancer on a population basis. Countries which ate more meat suffered more.

In 2007 the World Cancer Research Fund pulled together the results of 14 studies, concluding that red and processed meats were “convincing causes of colorectal cancer”. Their report suggested cutting out processed meat altogether and eating no more than 500 grams of red meat per week.

Now this:

Two large studies published in 2012 found that the risk of dying from all causes – including bowel cancer and heart disease – during the study follow-up period was 13 per cent higher for people eating 85 grams of red meat per day, and 20 per cent for those eating 85 grams of processed meat. That would translate to roughly a year off life expectancy for a 40-year-old man who eats a burger a day.

As often in health research, just when all that seemed clear complications set in. Such studies are based on self-reporting as to quantity and frequency and often didn’t discriminate between types of meat or tease out links with other life-style factors. In 2013 a European study:

followed half a million people in 10 European countries over 12 years, and as well as distinguishing between consumption of red meat, white meat and processed meat, it also controlled for factors such as smoking, fitness, body mass index and education levels, all of which might be correlated with high meat consumption.

The study found no association at all between fresh red meat and ill health, but the link with processed meat remained. It found that for every 50 grams of processed meat people consumed each day, their risk of early death from all causes increased by 18 per cent.

An American study of 18,000 people found no association between deaths from cancer or cardiovascular disease and the consumption of meat, even processed kinds, but was criticised for the crudeness of its questionnaire.

Further studies have now linked haem, the component that makes red meat red, with the generation of cancer cells.

Meat, however, remains a handy nutritional package, difficult but not impossible to replace. There is this caution about vegetarianism from the European study:

Perhaps the most surprising finding from the EPIC study was that those who ate no meat at all had a higher risk of early death from any cause than those who ate a small amount of red meat.

Vegetarians don’t always make healthy food choices.

The cautionary position seems to be that small amounts of meat are good – about 70 grams per day. (This does seem very cautious in the light of the European study.) It’s not clear whether it’s best to eat a small portion each day or save your allocation for a splurge. It does matter how you prepare meat and what you eat with it. Avoid chargrilling, eat plenty of fibre and for some reason let the cooked potatoes grow cold! Best to avoid processed meat if possible.

At the production end, there is masses of grazing land in the world that can’t be cropped. The methane, however, remains a problem, which can be mitigated in various ways. That, however, is another story.