It is almost axiomatic to say that the mitigation necessary for 2°C limit to warming is best delivered through market-based instruments (MBIs) – where a price is placed on each tonne of carbon dioxide emitted.

Dissenter-in-chief is Kevin Anderson, professor of energy and climate change at the University of Manchester and deputy director of the Tyndall Centre, the UK’s leading academic climate change research organisation:

I hold that such an approach is doomed to failure and is a dangerous distraction from a comprehensive regulatory and standard based framework (within which price mechanisms may play a niche role).

Crucial in making this judgement is the notion that the mitigation rates are not marginal. We don’t need to knock off just one or two percent of emissions each year. We need, says Anderson, a whopping 10% per annum.

That seems extraordinary, but I’ll repeat here three graphs I’ve used before. They all come from 2009, the last two from The Copenhagen Diagnosis.

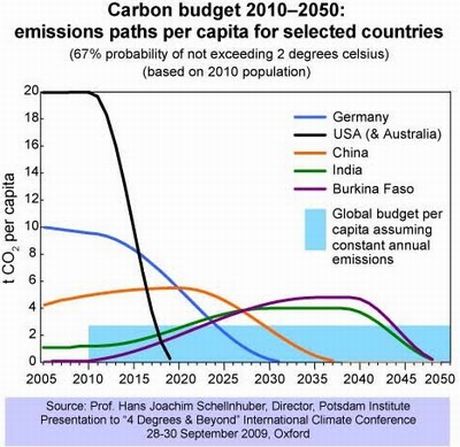

First we have Hans Joachim Schellnhuber’s estimate of the reductions needed using the ‘budget approach’, whereby the budget of permissible emissions is divided between countries on a per capita basis, and then the stabilisation path plotted given their existing per capita emissions levels:

Anderson variously says the ‘we’ need to reduce emissions by 80 to 90% by 2030 and to zero soon thereafter. I think he is referring to the UK, which would have a similar stabilisation path to Germany. Note that Schellnhuber is basing these trajectories on only a 67% chance of keeping warming within the 2°C limit.

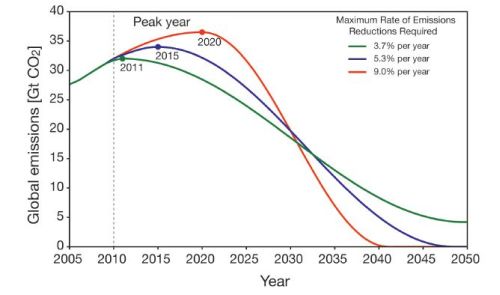

In the second graph the stabilisation path for the whole world is calculated, given different peaking dates:

That shows a 9% per annum reduction required to reach zero about 2040 with peaking in 2020. In those terms Anderson’s 10% figure is in the ball park.

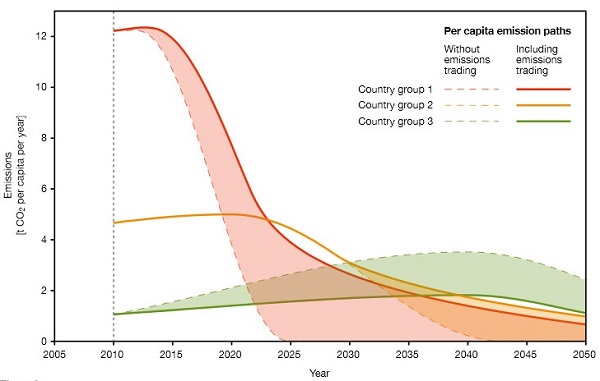

The third graph shows how the trajectories could be varied if countries were grouped into three categories, roughly advanced industrial countries, developing countries and in the middle newly industrialising countries. Carbon trading between them is assumed:

This too is a dangerous distraction. While rational it assumes that China, India and the US will commit themselves to definite reduction paths through international agreement. It’s simply not politically feasible.

I think Anderson is in the right ball park. His argument is that MBIs work fine when the reductions required are marginal. If you crank them up to get the result required a very high price will result. The rich will pay and continue to pollute while the poor will be devastated.

Anderson doesn’t discuss compensation, as was built into the Australian scheme, but pricing and compensation on the scale required is probably not politically feasible.

Anderson favours a regulatory or standards-based approach and gives these examples:

- Strict energy/emission standards for appliances with a clear long-term market signal of the amount by which the standards would annually tighten; e.g. 100gCO2/km for all new cars commencing 2015 and reducing at 10% each year through to 2030

- Strict energy supply standards; e.g. for electricity 350gCO2/kWh as the mean emissions level of a suppliers’ portfolio of power stations; tightened at ~10% p.a.

- A programme of rolling out stringent energy/emission standards for industry equipment

- Stringent minimum efficiency standards for all properties for sale or rent

- World leading low-energy standards for all new-build houses, offices etc.

- Moratorium on airport expansion

- Technological and operational standards for shipping operating in UK waters

- A suite of iterative mechanisms to counter, or at least alleviate, issues of rebound; this may include price mechanisms, progressive metering tariffs, etc.

- Revisit the viability of Personal Carbon Trading as a mechanism for improving societal engagement in non-marginal change

- Appoint a senior minister with the principal responsibility for maintaining an equitable transition to a low-carbon society

Taking the first two, rather than standards for appliances, I would focus on making stationary electricity supply renewable as an urgent task through direct action. Other than that all the ideas are grist to the mill, but I like John Wiseman’s approach as outlined in the post Climate change: reconnecting politics with reality which concentrates on the necessary political and institutional actions to be taken. After a priministerial announcement he recommends:

Then we would need an Australian Climate Solutions Act which set up the targets, the structures and the priority actions. Principal amongst these would be an Australian Climate Solutions Taskforce chaired by the Prime Minister and drawing from state and local governments, business, trade unions and community organisations.

Then we would need six key action plans.

First, an Australian Renewable Energy Plan to achieve 100 per cent renewable energy within 10 years.

Second, an Australian Economic Electrification Plan with initial priorities including a modal shift in passenger and freight transport from road to rail; the rapid replacement of fossil fuel based cars with electric vehicles; and the full electrification of household and industry heating and cooling.

Third, an Australian Energy Efficiency Plan that identifies the regulatory, planning, educational and financial initiatives that could achieve the overall goal of a rapid transition to a zero waste economy.

Fourth, an Australian Sustainable Consumption Strategy.

Fifth, an Australian Sustainable Agriculture and Forestry Plan designed to reduce land-based emissions and increase carbon sequestration.

Finally, state and local governments, community sector and business organisations would collaborate to develop and implement a comprehensive, long-term Australian Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Plan.

I applaud the priority Wiseman gives to an Australian Renewable Energy Plan to achieve 100 per cent renewable energy within 10 years.

Carbon pricing similar to the Australian scheme may be one of a suite of actions to send a message and raise funds, but climate action on the scale now required compels us to address the issues much more directly. Overall my aim for the planet would be to reduce atmospheric CO2 to 350 ppm by 2050, for a safe climate. Well, as safe as it ever gets.

Brian: It is almost axiomatic to say that economists tend to think that the answer to everything is price manipulation. However, this doesn’t mean that:

I have the same problem with people like Anderson who

As you well know I think that both approaches may be appropriate for dealing with particular sources of GHG. However, once people start to talk about them as “the answer to everything” they are guilty of lazy thinking.

If we are serious we have to take the effort to look at each source of emissions and work out the best way to deal with them.

I don’t think Anderson is lazy, it’s just that he lacks experience in government, and it shows. He’s given us a grab bag of bits and pieces. I think Wiseman’s approach is strategic and more appropriate. The detail comes with the specific plans.

There is a question, though, whether his matrix of plans is the best. For example he completely misses out planning for reduced emissions in mining, both as a process and as fugitive emissions. There also needs to be specific attention given to all six Kyoto gases, not just CO2, which may or may not be covered by what he has laid out.

Brian: A key action is shutting down the coal mines and gas wells. The fugitive gas problem goes away once this is done properly.

I think that there has been too much stuffing around with great big government action and we need to get on with the things that governments at all levels etc. can do.

John, I agree that we need action at subsidiary levels of government, but the Feds also need to act in a major way.

I don’t like any of the market jiggery-pokery at all. Set emission standards – enforced by a set date. Those who comply, stay in business; those who don’t, go out of business – and none of this “too big to fail” or “think of all the job losses” deceptions either.

Graham: If we are talking about large scale renewables, market based systems work well if they come in the form of competitive tendering for contracts to supply renewable capacity. They can also work for rooftop solar when linked to automatic bidding.

Market based systems based on offset credit trading can also be very effective at driving down averages. Ideal for driving down the average fuel/energy consumption of new cars. (Avoids the arguments that arise when a new standard is proposed that will block some cars from the market.)

Standards can work well for simple cases such as electric globe efficiency.

In many cases what is required is enabling legislation. For example, legislation that sets out width requirements for narrow track vehicles.

And….

The message is do the homework properly and then decide how to drive the change.

Other message is that the strategies will be different if we want to get it all done in 10 yrs instead of 30.