Recently John Quiggin in The fossil fuel crash of 2014 asked what should we make of the fact that oil prices have fallen from more than $100/barrel in mid-2014 to around $60/barrel today? He also looked at coal, I’ll stick with oil. Quiggin poses the questions:

The big questions are

(i) to what extent does the price collapse reflect weak demand and to what extent growing supply

(ii) will these low prices be sustained, and if so, what will be the outcome?

Quiggin says:

The answer to the first question seems to be, a mixture of the two, with some complicated lags.

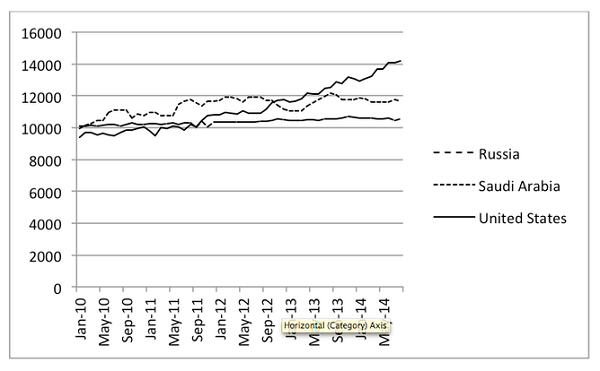

I thought it was the Saudis increasing supply to put the American frackers out of business. This turns out not to be the case. Richard Heaney gives us this graph on monthly oil production:

So it is the Americans who have largely increased supply. The Saudis have simply decided not to reduce supply, the usual tactic to increase the price. I’m sure they are hoping the American frackers will feel the squeeze.

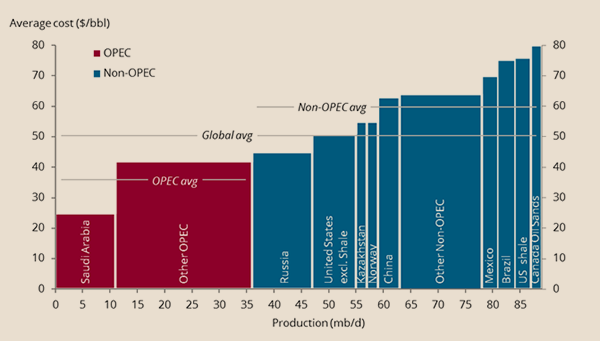

Anjli Raval gives this graph of costs:

Raval says that most at risk are the Canadian oil sands, US shale plays and other areas of “tight oil”. Also vulnerable are Brazil’s deepwater fields and some Mexican projects. Crude at $70 puts at risk projects for 2016 to the extent of 1.5 million barrels per day.

Raval has perhaps the best discussion of what might happen in the future. The short answer is that we don’t know. A pull-back in investment could lay the basis for the next price surge. There may also be a switch to cleaner energy sources.

Much of the discussion, including a Financial Times editorial arguing that the fall in the price of oil was good for the economy (the concern was over deflation), ignores climate change.

John Quiggin says, inter alia that:

if we are to reduce emissions of CO2, a necessary precondition is that the price of fossil fuels should fall to the point where it is uneconomic to extract them.

I’m confused. I thought the aim of carbon pricing was to make fossil fuels more expensive to discourage use and to make the use of renewable alternatives competitive.

Adair Turner in a piece Please Steal Our Fossil Fuels goes into considerable detail about the transition to renewables. If all the fossil fuels were stolen we would not be stuck (or not for long) and it would in the long run cost a negligible amount more. However, the assumption is that the transition will depend on price. Unfortunately electric cars may not be cheaper until the late 2020s. There is plenty of oil in the ground and whilst it is available we will keep using it.

Turner says “we should commit to leaving most fossil fuels forever in the ground” and no great harm would befall us economically if we did, but we won’t. Miracles would be required.

At this point I’ll state my case that we should act out of policy, not rely on markets or miracles. If Germany can forswear nukes because they are dangerous and evil, why can’t we do the same in relation to fossil fuels, which are even more dangerous? Sooner or later we’ll have to ignore the fossil fuel mafia.

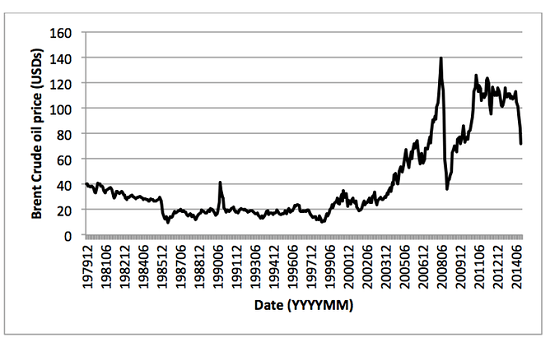

Before I go, Heaney has this graph of the oil price in recent years:

It demonstrates that oil can be extremely volatile. There is no way of telling where the current crash will end, but my guess is that it will more or less stabilise soon. After that we are in uncharted territory.

Elsewhere Jeffrey Frankel makes several interesting points.

Firstly most dollar denominated commodities have fallen in price, including iron ore, silver, gold, platinum, sugar, cotton and soybeans. So something general is going on beyond the vagaries of specific commodities.

Secondly, The Economist’s euro-denominated Commodity Price Index has actually risen over the last year.

Third, and most importantly, it seems, there is a link between commodity prices and interest rates. When interest rates go up, commodity prices fall. Frankel suggests that traders are anticipating a rise in interest rates in the US next year. It’s not the whole story, but perhaps an important factor overlooked elsewhere.