Continue reading 9 Out of Ten Australian Households are Considering Solar

Daily Archives: October 16, 2014

Ebola: how bad will it be?

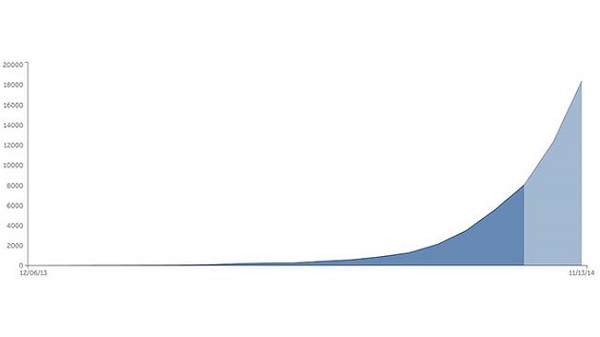

In Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, three neighbouring West African countries, Ebola seems to be out of control. This is a graph of the numbers of new cases with projections for the next four weeks in lighter blue:

So far there have been about 8,400 cases and some 4,000 deaths. There are claims that cases in Liberia are doubling every 15-20 days while those in Sierra Leone are doubling every 30-40 days. By the end of the year there could be as many as 18,000 new cases weekly.

I’m impressed though that there has been no spread to other African countries other than Nigeria, where it appears to have been contained. One case surfaced in Lagos in July with 19 subsequent infections. However, the chain of contagion seems to have been broken.

On the other hand subsequent infections in the US, where a second health care worker has tested positive, and Spain are cause for concern.

You can read very different views of the potential impact of the disease worldwide. This Nature article is quite definite that the Ebola does not represent a global threat. The virus is too hard to catch and advanced country health systems are too sophisticted. By contrast this New York Times piece worries about the virus gaining a foothold in a mega-city somewhere else in the developing world. I’d worry about India and the capacity of its health system to cope.

The current outbreak is the first time the disease has gained a foothold in urban areas.

A second worry is that the virus may become airborne. C Raina MacIntyre, who is Professor of Infectious Diseases Epidemiology and Head of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine at UNSW, points out that experienced health care workers who have contacted the disease have not been able to identify how they caught it. The assumption is simply that there has been a breach in protocol. We keep being assured that the disease is hard to catch. While the long incubation phase, up to three weeks, does not help memory, the fact that it keeps happening in ways that can’t be precisely pinpointed is troubling.

Still, the circumstances that saw the disease take hold in West Africa are unlikely to be repeated. This Vanity Fair article explains how the spread of Ebola was assisted by unique circumstances.

Firstly Ebola was not identified for three and a half months. The disease was virtually unknown in West Africa; earlier outbreaks had been in central and east Africa. At first cholera, then Lassa fever were suspected. By the time Ebola was identified the disease had already spread to a number of towns, including a bustling trade hub.

The reaction of first world agencies was swift. After identification in late March, Guinea was invaded by strange robotic white people who came in space suits and took ill people away.

The foreigners had come so fast that they had actually out-run their own messaging: there were trucks full of foreigners in yellow space suits motoring into villages to take people into isolation before people understood why isolation was necessary.

To a villager, the isolation centers were fearsome places. They offered a one-way maze through white tarpaulins and waist-high orange fencing. Relatives or friends went in and then you lost them. You couldn’t see what was happening inside the tents—you just saw the figures in goggles and full-body protective gear. The health workers move carefully in order to avoid tears and punctures; from a distance, the effect is robotic. The health workers don’t look like any people you’ve ever seen. They perform stiffly and slowly, and then they disappear into the tent where your mother or brother may be, and everything that happens inside is left to your imagination. Villagers began to whisper to one another—They’re harvesting our organs; they’re taking our limbs.

The people in Guinea were as frightened by the response to Ebola as they were by Ebola itself. By May the cases dried up and the aid agencies started to relax. In fact the sick were hiding, as soon became apparent.

Rather than under control the reverse was true, the epidemic was completely out of control. While new strategies are gaining the trust of the people, the disease has outrun attempts to contain it.

There must be a huge effort to contain the disease within the three countries where then disease is endemic while a vaccine, currently under development, is fast tracked. As to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, we can’t just write off a combined population of over 20 million people. Health workers are in the front line and these countries human health worker resources are being depleted by the disease. Liberia has only 250 doctors left for 4 million people, that’s one for every 16,0000 people.

Yet Australia has seen no great obligation to help. Officially I understand we have supplied about $18 million in aid, a pathetic amount, while our fearless prime minister has said that it is too dangerous for us to put boots on the ground. Yet there is work to be done out of direct contact with patients, in building temporary field hospitals, for example. Our PM could show just a bit of compassion and genuine humanitarian concern.