At Carbon Brief the most read post is The what, when and where of global greenhouse gas emissions: A visual summary of the IPCC’s climate mitigation report from 13 April 2014. It is an excellent post, condensing the message of a complex report. What a pity that it is completely out of date and more than a little misleading in terms of current scientific realities!

The problem is that because of the publishing cycle and the compilation process in putting together the IPCC reports the science they are based on is about three years old at time of first appearance. Then the IPCC reports are quoted in the media as gospel for a further seven years.

As I explained back in June in The game is up following a David Spratt post from May, there is no burnable carbon left if we want a reasonable chance of a safe climate. I repeat here three quotes from Spratt:

We have to come to terms with two key facts: practically speaking, there is no longer a “carbon budget” for burning fossil fuels while still achieving a two-degree Celsius (2°C) future; and the 2°C cap is now known to be dangerously too high.(My bold)

He says we need to take a proper approach “around contingency planning for high-impact and what were regarded as low-probability events, which unfortunately are now becoming more probable”.

If a risk-averse (pro-safety) approach is applied – say, of less than 10% probability of exceeding the 2°C target – to carbon budgeting, there is simply no budget available, because it has already been used up.

We all wish the incremental-adjustment 2°C strategy had worked, but it hasn’t. It has now expired as a practical plan.

There is no longer a non-radical option, only one path remains viable: the emergency ‘war economy’ mode.

Even when it was written the IPCC report was problematic. Take for example this statement in the Carbon Brief summary:

It shows that if emissions between 2005 and 2030 are within the dark green chunk on the left panel, then reductions between 2030 and 2050 would need to be around three or four per cent a year (the dark green bar on the middle panel). If emissions follow a path within the lighter green chunks on the left, reductions will have to be closer to five or six per cent a year between 2030 and 2050 (the lighter green bars in the middle panel).

In October last year I posted this graph from Malte Meinshausen which dates from 2009:

In other words if we leave peaking until 2030 we will need annual reductions of emissions of 22.6%, reach zero by 2043 and then go negative. That was before the “carbon budget” shrunk.

In my view the world should aim peak by about 2020, try to reach zero by 2030 and then go negative. In Oz as the largest per capita emitter of the major economies we should be aiming for 45 to 50% reductions by 2020.

The portrayal of the problem as it stands in the Carbon Brief post is in my view dangerously irresponsible. In my own summary of the mitigation report in May I called the approach taken “reckless”.

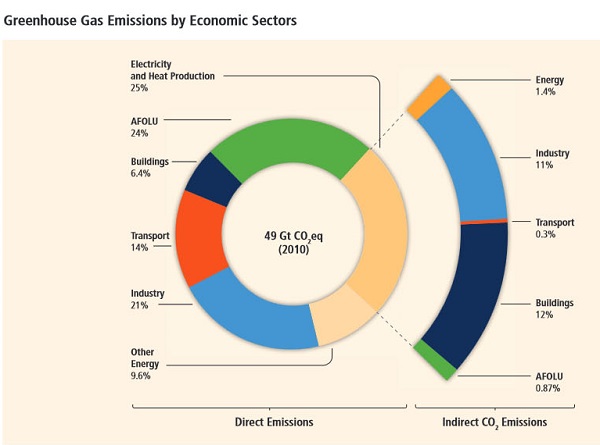

Nevertheless it has a useful graphic which gives an overview of where the emissions are coming from:

Our focus tends to be on electricity and motor vehicle transport, which amount to less than half of the problem. The green AFOLU segment represents agriculture, forestry and land use, a segment that is particularly difficult to deal with.

There is much to be done!

Brian: If we go on a climate war footing the implication to me is that we will do whatever it takes to get to zero fossil carbon use within a fairly short time period. I don’t know enough to be sure that the need for fossil carbon can be completely avoided. However, with currently available technology we can:

1. Move to 100%, renewable power.

2. Use this renewable power to:

a. Directly drive many forms of transport.

b. Produce transportable fuels that can be use in planes, ships etc.

c. Replace the use of gas for cooking, heating buildings and many industrial processes.

d. Produce renewable feedstocks for the petrochemical industry.

e. Produce renewable ammonia for use as a transport fuel and the feed stock for a range of fertilizers and nitro chemicals.

f. Produce hydrogen as a feed stock for a wide range of chemicals as well as the replacement of carbon in metallurgical processes such as ironmaking

3. Turn cement into a CO2 consumer instead of a CO2 producer by replacing limestone based cements with things like magnesium silacate based cements

I really don’t know about agriculture but I suspect most agriculture emissions are part of natural cycles and do not involve the consumption of fossil carbon.

In practice, what needs to happen will be simpler than it appears now because of improvements in energy efficiency, changes in the way we use energy and changes in the mix of products we use because of changes in relative costs.

John, that all looks doable and not terrifying. What would cause alarm would be the write-down in asset value within the fossil fuel industry and associated power generation industry if we got serious about phasing it out.

The AFOLU segment would include clearing tropical rainforests, so it’s hard to say how much is accounted for by farming. Some thoughts.

If planes and ships can be run a fossil fuel free basis farm tractors and such should be no problem. Already I have heard of instances of farmers creating their own biodiesel.

Methane producing ruminants are an issue. Various mitigation strategies are being worked on. From memory a 2007 Queensland Government report found that the beef industry was emissions neutral when the growth of trees was taken into account.

Fertilizer produced nitrous oxide, I think, the next most problematic GHG after CO2 and methane. Not sure what can be done.

I think rice paddies produce a fair bit of methane. Again I’m not sure what can be done.

Increasing soil carbon is good farming practice, but problematic if you want to measure and count it.

One way or another, we need to eat and farming emissions will need to be dealt with.

Brian: I think the focus has to be on fossil carbon. The methane produced by burping ruminants, paddy fields etc. is part of a natural cycle that converts atmospheric methane into ruminant feed. There are approximately 150 species of rumninants including cattle, goats, sheep, giraffes, yaks, deer, camels, llamas, antelope, and some macropods. (Macropods, such as kangaroos produce less methane than cows etc.)

The nitrogen that escapes from fertilizer is also part of a process that recycles atmospheric nitrogen compounds back into the soi and/or breaks up the compounds in the atmosphere to release nitrogen. (The real issue with nitrogenous fertilizers is that the bulk of their production currently produces carbon dioxide.)

This doesn’t mean that we should ignore land clearing since the amount of carbon held in trees, soil etc is significant. I did read somewhere, however, that in the drier parts of the US grassland holds more carbon than the sort of scrub that grows in these lands.