Noel Cameron-Baehnisch in a rush of enthusiasm has translated the Dąbrówka Wielkopolska (fmly Groß Dammer) article in Polish Wikipedia. This may mainly be of interest to specialists and enthusiasts but the persistent will be rewarded. I’ve added here some images from the article, first the famous folkloric church:

Next to the church stands a belfry:

Here’s the famous chateau, apparently as it appeared in 1858:

This is a more modern version, in a winter mood:

This is a park scene in the chateau complex:

In the centre of the village we find an attractive pond:

Related articles may be found under the tag Bahnisch family history.

Here’s Noel:

My rough translation of the Polish WIKIPEDIA article: found 7/7/2014; translated word-by-word using the Internet on the 9 July 2014. Dabrowka (pronounced “dom-BROOF-kah”) is the village where my Polish ancestors, the Ruciaks (“ROO-chark”), came from; they were Prussian subjects but ethnically very Polish. I assume the information in this WIKIPEDIA article is accurate, though I know it consists of contributions from one person or several people, none of whom can be classified as professional historians. WIKIPEDIA is free; professional history is not.

Dąbrówka Wielkopolska (niem. Groß Dammer [2]) – wieś w Polsce położona w województwie lubuskim, w powiecie świebodzińskim, w gminie Zbąszynek.

Translation notes: Polish is a heavily inflected language; words typically consist of a stem followed by all sorts of complex “inflections” or case endings, like in Greek, Latin, Russian and German).

niem. (abbreviation) = German. wies = village (“-wice” in placenames; wsi = in the village). “w” is a preposition which means in, towards, to, etc.

Village on Polish territory, in the Lubuska Province, District of Swiebodzin, sub-district of Zbaszynek (the modern industrial and railway town just south of Dabrowka).

Państwo Polska [Nation of Poland]

Województwo lubuskie [Province of Lubuska]

Powiat świebodziński [District of Swiebodzin]

Gmina Zbąszynek [Sub-district of Zbaszynek]

Liczba ludności (2010) 1172 [1] [population in 2010]

Strefa numeracyjna (+48) 68 [telephone area code]

Tablice rejestracyjne FSW [car number-plate begins with “FSW”]

Spis treści [List of Contents]

1 Historia [history]

2 Zabytki [monuments]

3 Galeria

4 Przypisy [references]

[Brian – The above images appeared from nowhere. The aren’t in the Word file Noel sent me, or in the back-end copy that generates the post, so I can’t remove them!]

Historia

Miejscowość wzmiankowana była już w 1406 jako wieś szlachecka Dambrowca w dobrach zbąszyńskich. W XV w. osada była w posiadaniu rodziny Zbąskich. Niestety we wsi nie zachowała się stara kronika z XIV w. napisana po łacinie i po polsku przechowywana w miejscowym kościele św. Jakuba Apostoła, ponieważ wypożyczona została przez Uniwersytet Humboldta w Berlinie i nigdy już do Dąbrówki nie powróciła [3].

Zbaszyn = German Bentschen, an important town just SE of Dabrowka; many families left the Bentschen district for South Australia. Neubentschen (New Bentschen) = Zbanszynek.

This place was mentioned as early as 1406 as the wies szlachecka (noble village = village owned by an aristocrat) of DAMBROWCA in the Zbaszyn Town records. W XV. wieku (in the 15th century) this settlement (osada) was the possession of a Zbaszyn family. Unfortunately the village no longer has its stara kronika z XIV w. (14th-century Old Chronicle), written in Latin (po lacinie) and Polish (po polsku) and stored in the Church of Saint James the Apostle (Jakuba Apostola) – because it was borrowed (wypozyczona) by the Humboldt University in Berlin (the oldest and most prestigious university in Berlin) and nie powrocila (never returned)!!

Osada zbudowana na planie tzw. owalnicy z charakterystycznym placem wewnętrznym, zwanym nawsiem.

z = the preposition means with, from, about, out of, because of, in, etc.

Settlement built on a so-called oval (owalnicy) plan with characteristic … … [too difficult for me to translate the rest].

Mimo bezpośredniego sąsiedztwa z niemieckim obszarem etnicznym i procesów germanizacyjnych, polska ludność autochtoniczna stanowiła zawsze większość mieszkańców zachowując polską mowę i obyczaje. W 1905 we wsi mieszkało 1.038 osób, w tym 90,1% Polaków oraz 9,7% Niemców [4].

niemieckim = the stem niem plus a complex inflection and case ending = German.

Despite (mimo) the closeness of ethnically German territory and the process of Germanification (procesow germanizacyjnnych), the native population always (zawsze) preserved (zachowujac) its polska mowe i obyczaje (Polish language and customs). In 1905, we wsi (in the village) were 1038 people, of whom 90.1% were ethnically Polakow (Polish) and 9.7% ethnically Niemcow (German).

W 1910 jako dominium Gross Dammer miejscowość należała do Bernharda von Britzke. Mimo protestów polskiej ludności w 1919 pozostała w granicach Rzeszy na mocy decyzji komisji międzyalianckiej. W latach 1815-1945 Dąbrówka Wielkopolska należała do powiatu międzyrzeckiego (Kreis Meseritz).

In 1910, the “dominium” of Gross Dammer was owned by the aristocrat, Bernhard von Britzke (von is the aristocratic adjective and Britzke looks like a Slavic name; Bernharda is in the genitive case): in other words, the village was owned by Von Britzke, who obviously lived in the big palac (chateau). Despite (mimo) the protests of the Polish population in 1919, it remained inside the border of the Rzesz (Polish form of Reich), because of a decision by an international commission. In the years 1815-1945, Dabrowka belonged to Kreis Meseritz (the Prussian District of Meseritz Town).

W latach 1929–1939 we wsi działała polska szkoła, w której nauczało 3 nauczycieli, a uczyło się 140 dzieci [5]. Szkoła po raz pierwszy wzmiankowana była w 1640. W miejscowości istniało także przedszkole polskie założone w 1935 roku, z 70 dziećmi.

In the years 1929-1939, the village operated its own Polish school (polska szkola), in which 3 teachers (nauczycieli) taught about 140 dzieci (children). The school was pierwszy wzmiankowana (first mentioned) in the year 1640. There was also (takze) a Polish kindergarten (przed-szkole polskie), founded in 1935, with 70 youngsters (dziecmi).

W 1939 na 1.287 mieszkańców wsi Polaków było 986. We wsi w 1923 powstaje Polskie Towarzystwo Gimnastyczne Sokół założone przez Stanisława Mizernego, które posiadało męską i żeńską sekcję sportową. W miejscowości istniał także oddział regionalny Związku Polaków w Niemczech, Przysposobienie Rolnicze, Chór Polski oraz Kółko Rolnicze.

In 1939, of the 1287 village residents, 986 considered themselves to be Polakow (Poles). In the village, in 1923, was founded a branch of the POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO GIMNASTYCZNE “SOKOL” by Stanislaw Mizern, which had male and female sporting sections. (This “Falcon” Polish Gymnastics Society was part of the Pan-Slavic Movement.) The village also (takze) had a regional branch (oddzial) of the non-political Zwiazku Polakow w Niemczech [Union of Poles in Germany], a Przysposobienie Rolnicze [agricultural college], a Chor Polski [Polish choir] and a Kolko Rolnicze [agricultural “circle” or club].

W 1934 roku, utworzono stały obóz Arbeitdienstu. W 1935 miasto Lipsk rozpoczęło tuż przy Dąbrówce budowę osady niemieckiej pod nazwą Limbach, dla uczczenia SA-manna Limbacha, zabitego w walce nazistów z komunistami. Wg oceny niemieckiej gazety “Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung” osada ta powstała w celu wzmocnienia żywiołu niemieckiego “muszącego ciężko walczyć na Pograniczu z mniejszością polską”[6]. W lipcu 1938 roku, nastąpiło uroczyste poświęcenie 20 gospodarstw, wielkości 20 ha każde przeznaczonych dla niemieckich kolonistów-członków SA i SS [5].

[In 1933 Hitler ruthlessly grabbed power and strangled German Democracy.] In 1934, an Arbeit-dienst camp was set up. In 1935 the City of Leipzig (Lipsk) began to construct osady niemieckiej (German settlements), called Limbach after an SA soldier of that name, killed in Nazi action against German communists. (SA = Nazi Brownshirts.) According to the German newspaper (gazety) “Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung”, the settlement was founded to strengthen the German presence in those border districts z mniejszoscia polska (with Polish minorities). In lipcu (July) 1938, there was a ceremony to dedicate 20 gospodstw (farms), each of 20 hectares, mainly for niemieckich kolonistow (German colonists) who were czlonkow (members) of the SA and SS. [You can be sure these colonists left quickly in 1944, of their own volition! Limbach is now called Samsonki, about 3 km east of Dabrowka.]

Podczas wojny, polskojęzyczna ludność Dąbrówki była przez Niemców wysiedlana i zsyłana do obozów koncentracyjnych, dotyczyło to szczególnie polskich działaczy społecznych i narodowych, np. Jana Budycha współorganizatora Banku Ludowego i jednego z organizatorów polskiej szkoły w Dąbrówce Wielkopolskiej. Łącznie zginęło 12 osób [7].

During the War (“wojn” is the stem for “war”), polskojezyczna (Polish-speaking) residents of Dabrowka were arrested by the Germans and sent to obozow koncentracyjnych (concentration camps), especially Polish social and nationalist activists (dzialaczy), such as Jan [John] Budych, managing-director of the local People’s Bank and one of the organizers of the local Polish schools (polskiej szkoly) in Dabrowka. Lacznie (in total) zginelo (were murdered) 12 osob (people), by the Nazis, including Jan.

(The surname Budych is significant because Carl Albert Budich [sic: “BOO-dik”] (1839-1911) married Franziska Naida (1845-1891) in 1863 in South Australia: Franziska was the niece and namesake of Franziska Baehnisch nee Ruciak (Ruciack); Fran Naida’s mother was Severina Ruciak, Fran Baehnisch’s sister. The Budich (Budick) surname is still found in South Australia. So are the surnames Naida (Nayda) and Ruciack. All these families left Dabrowka district and so missed out on the trauma and horrors of two idiotic ultra-nationalistic World Wars. Instead, they had the privilege of helping to destroy an out-of-control ultra-militaristic Germany, then watching from afar the formation of two new and peaceful Germanys, one free, one not free, next to a proud and independent, if not free, Poland.)

W 1945 wieś została przyłączona do Polski. W uznaniu zasług w zachowaniu polskości wieś, w 1973 została odznaczona Krzyżem Grunwaldu II klasy. W latach 1945-1954 siedziba gminy Dąbrówka Wielkopolska. W latach 1975-1998 miejscowość administracyjnie należała do województwa zielonogórskiego.

In 1945, the village (wies) was attached to Poland. In recognition of its meritorious behaviour as a polskosci wies (Polish village), in 1973 it was awarded the Grunwald Cross (Second Class). (In the battle of Grunwald, in 1410, the Poles crushed the Teutonic Knights.) From 1945-1954, it was in the sub-district (gminy) of Dabrowka. From 1975-1998, it was administered by the Province of Zielona Gora. [1998 marks the end of Communist Poland.]

Siedziba Parafii Niepokalanego Poczęcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny i św. Jakuba Apostoła.

Seat of the Parish of the Niepokalanego Poczecia (Immaculate Conception) Najswietszej Maryi Panny (of the Blessed Virgin Mary) and of Saint Jakub Apostol (James the Apostle).

Zabytki [Monuments]

Według rejestru Narodowego Instytutu Dziedzictwa na listę zabytków wpisane są [8]:

According to the National Heritage Institute’s list of registered monuments:

kościół parafialny rzymsko-katolicki pod wezwaniem Niepokalanego Poczęcia NMP, z połowy XVII-XVIII wieku

zespół pałacowy: pałac, neorenesansowy z lat. 1856-1859; park, z połowy XIX wieku.

kosciol (pronounced “KOSS-ya-choo-wa”) = church. parafialny = parish (adj.). rzymsko-katolicki = Roman Catholic. pod wezwaniem = called. z polowy XVII-XXIII wieku = [built in] mid-17th century to 18th century.

Chateau complex: the palac [“PAH-wah-ts”] or chateau, Neo-Renaissance, [built] in 1856-1859. And the chateau’s park, mid-19th century.

Galeria

1. Kościół par. pw. Niep. Poczęcia NMP [parish church called the IC of the BVM]

2. Pałac [palace or chateau]

3. Park w zespole pałacowym [park in chateau complex]

4. Staw w centrum wsi [pond in centre of village; staw is pronounced “STAH-ff”.]

5. Neorenesansowy pałac [Neo-Renaissance chateau]

6. Pałac na ilustracji z 1858 r. [chateau illustrated in 1858 year]

7. Dzwonnica przy kościele parafialnym [belfry beside the parish church]

[Brian – again the images appeared from nowhere. Curious because what we have here is not co-extensive with what appears in the linked article.

Przypisy [References]

Reference [4] is the most interesting one:

Na podstawie danych ze spisu powszechnego z 1905 r., wg deklarowanego języka ojczystego i religii; część ludności zadeklarowała inny język ojczysty. Gemeindelexikon für das Königreich Preußen. Heft V. Provinz Posen, Berlin 1908.

Based on data collected by the Census (spisu) of 1905, based on stated (deklarowanego = declared) jezyka ojczystego (native language = mother tongue) and religii (religions); segment of population declaring “other” (“inny”) native language. Parish Lexikon for the Prussian Kingdom. Volume 5. Province of Posen (Poznań in Polish). Berlin, 1908.

And finally, I must tackle the text of one of the 3 plaques I photographed in 2004 on the outside of the parish church. Our Polish guide Bolek told me the 12 listed people had died in WWII. I had always guessed that they were young men compulsorily drafted into Hitler’s armies and then killed in action. But I know better now. And I must apologize to the families of the 12 martyrs, who are my very distant cousins, for the misunderstanding. This is what happens when a family forgets how to speak Polish. Please pardon any bad transcription errors because it is very hard to read the beautifully carved text on the marble plaque. When I read about Jan Budych’s fate in the WIKIPEDIA article, I began to understand the following:

Boże zbaw Polskę. God bless Poland.

Bohaterom Dąbrówieckim. To the Martyrs of Dabrowka. (bohater = martyr.)

Milość. Wierność. Cześć. Love, Fidelity. Honour.

Jan Budych, Tomasz Budych, Marcin Bimek, Walenty Berent, Wojciech Berowicz, Jan Flejsierowicz, Wojciech Golek, Jan Golek, Antony Kwaśny, Stanisław Kędziera. Piotr Malysiak, Wojciech Młodystach.

Some of the surnames are Germanic or partly so (Flejsier = Fleischer?). Młodystach is very prominent in the South Australian Phone Book today: now spelt Modistach but unmistakably Polish; in modern Polish, the l-with-stroke ( ł ) is pronounced like the English ‘w’ sound – “m-WOR-dee-stah-k”.

Za Waszą Wiare i Wolność. For Your Faith and Freedom.

Życie Swe Oddali. They Gave Their Lives. (word-for-word, Lives Their They-Gave.)

This is an echo of Poland’s unofficial National Motto, which dates back to the disastrous 1830 Polish Insurrection: Za Naszą i Waszą Wolność (For Our and Your Freedom). The 12 Martyrs of Dabrowka not only fought for their own Freedom but for the Freedom of Everyone, then and now, for you and me.

Męczarniach Więzień i Obozów. Tortured to death in Prisons and Camps.

Miłosier Bądż ——-. Mercy Be ——–. Probably “upon their souls” or “upon all”.

And I can’t read the last line on the plaque.

Finally, Reference [2] makes reference to the “Rodło”. I GOOGLEd this and read a fascinating story of adaption and survival. Kaczmarek died in exile in Washington DC in 1977; Kłopocka died in Communist Warsaw in 1982. Prussia had long before banned the use of the White Eagle as a Polish symbol inside Prussia. Hitler seized power in early 1933, so it seems the symbol was adopted before he rose to dictatorial power, despite what the English WIKIPEDIA article implies. I have edited the text slightly. In Polish, the Vistula is called the Wisła (”VEE-s-wah”). Rodło = “ROR-dwor”.

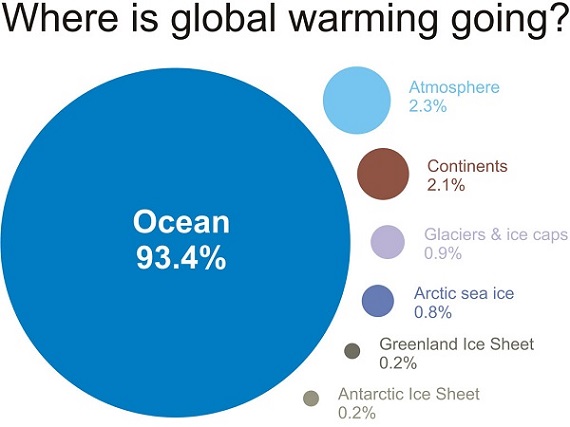

The Rodło is a Polish emblem used since 1932 by the Union of Poles in Germany. It is a stylized representation of the Vistula River and Kraków as the wellsprings of Polish culture.

After Adolf Hitler had seized power in Germany, Nazi emblems were soon compulsory nationwide. The swastika became the national emblem of the Third Reich and Poles from the Union of Poles in Germany could not use their national symbols anymore, because they were prohibited. Dr. Jan Kaczmarek approached the supreme council with the following proposal:

“Our acceptance of the swastika and the German Greeting [the Nazi Salute] could only signify agreement to total Germanisation. Therefore we must find a way, without risking the accusation of anti-state activity, of not accepting Heil Hitler and the swastika (…) we should at last have our own national symbol, which would enable us publicly to set ourselves free from the Nazi swastika.”

The Rodło graphic was conceived by graphic designer Janina Kłopocka who sketched the course of the Vistula River, cradle of the Polish people, and Royal Kraków, cradle of Polish culture. The white emblem was placed on a red background – the Polish national colors. It was adopted in August 1932 by the leadership of the Union of Poles in Germany.

This clever modern image combines the Rodło on the right with an explanatory graphic on the left.

The Polish WIKIPEDIA article says in part:

… i zewnętrznie wyglądające jak pół zmodyfikowanej swastyki, a jednocześnie nią nie będące. W ten sprytny sposób, Polacy w Niemczech uniknęli przyjęcia symboliki nazistowskiej.

… and outwardly looked like half a modified swastika, whilst not actually being that. In this clever way, Poles in Germany avoided the adoption of Nazi symbols.

We all have so much to learn about our Polish ancestors!

Please correct any Polish typos, Polish Clerical Errors, etc.

By Noel David Cameron-Baehnisch, 7 Park Road, Angaston 5353 SA; ncameron@vtown.com.au.

Brian: I can’t find the above image in the current article. It seems to have been replaced by this one: