After the rally on Sunday 17 November Ben Eltham took a look at climate activism in the digital age and nominated climate policy as “the central battleground of 21st century politics.” Sooner or later, somehow or other, climate activism has to be turned into real politics. As one of the ten themes in the Centre for Policy Development’s Pushing our Luck: ideas for Australian progress Professor John Wiseman, Deputy Director of the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute at the University of Melbourne looked at the shape of climate policy for the future.

You can find his whole piece at page 142 on the pdf counter, but I’ll attempt to give a brief outline here.

First he surveys the science, our prospects and the risks. The risk of a 4C future is unacceptably high. He quotes the World Bank’s report Turn Down the Heat:

- ‘Even with the current mitigation commitments and pledges fully implemented there is roughly a 20 per cent likelihood of exceeding 4°C by 2100. If they are not met warming of 4°C could occur as early as the 2060s.’

What does 4°C mean?

- Professor John Schellnhuber, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, provides a stark assessment of the difference between a rise of two and four degrees. ‘The difference,’ he says, ‘is human civilisation. A 4°C temperature increase probably means a global [population] carrying capacity below 1 billion people’.

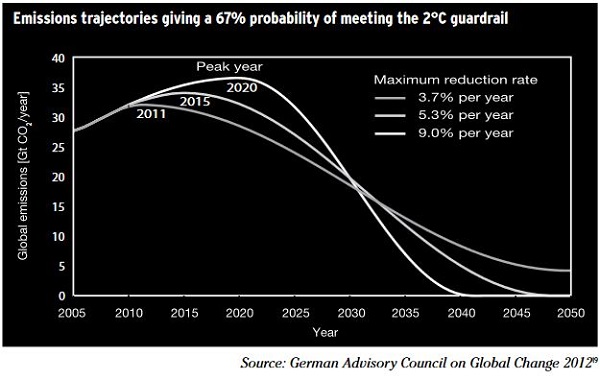

He then looks at the climate budget approach and posts a version of this now familiar graph:

He concludes that we need more ambition and urgency, both at the national and international levels. The achievement of emission reductions at the necessary scale and speed will require transformational rather than incremental change.

Wiseman goes for a three-phase emissions reduction target regime.

First, a 50% reduction target by 2020.

Second, zero net emissions by 2040.

Third, a carbon draw-down phase to get concentrations below 350 CO2e ppm.

I applaud his ambition, but, personally, would change the date of the second to 2030 and put a date of 2050 on the third. That is, we should aim for 350 CO2e ppm by 2050.

Wiseman says that if you look at the simple mathematics of the carbon budget approach you are compelled to set such targets. And

- While the achievement of an emissions target at this speed and scale is clearly extremely challenging, critics who argue that this task is simply impossible have a responsibility to reflect and speak honestly about the full consequences of inaction and delay.

In fact, he says, if we want to avoid crossing critical climate tipping points, there is a case for going harder. I totally agree.

Along the way we need to ditch the massive coal mining expansion planned by Australian companies and governments as it is “one of a handful of projects in the world that would take the planet beyond the point of no return if they were to go ahead.”

This, I think, is the uncomfortable elephant in the room for Labor policy makers. The other mob will never see it, so bipartisanship is not a possibility in this country.

Wiseman then surveys action around the world, which is not waiting for Australia, before laying out the structure of a plan.

To begin:

- we would need a clear and unequivocal public commitment by the Prime Minister that the Australian Government’s highest priority is to achieve an emergency speed transition to a just and resilient post-carbon economy. The Prime Minister’s announcement would emphasise the importance of setting and achieving emissions reduction targets and a clear recognition of the risks involved in failing to act. The statement would also call on all State and local governments, business, trade union and community organisations to demonstrate the strong moral leadership and decisive action required to meet Australia’s national emission reduction and carbon budget target.

Then we would need an Australian Climate Solutions Act which set up the targets, the structures and the priority actions. Principal amongst these would be an Australian Climate Solutions Taskforce chaired by the Prime Minister and drawing from state and local governments, business, trade unions and community organisations.

Then we would need six key action plans.

First, an Australian Renewable Energy Plan to achieve 100 per cent renewable energy within 10 years.

Second, an Australian Economic Electrification Plan with initial priorities including a modal shift in passenger and freight transport from road to rail; the rapid replacement of fossil fuel based cars with electric vehicles; and the full electrification of household and industry heating and cooling.

Third, an Australian Energy Efficiency Plan that identifies the regulatory, planning, educational and financial initiatives that could achieve the overall goal of a rapid transition to a zero waste economy.

Fourth, an Australian Sustainable Consumption Strategy.

Fifth, an Australian Sustainable Agriculture and Forestry Plan designed to reduce land-based emissions and increase carbon sequestration.

Finally, state and local governments, community sector and business organisations would collaborate to develop and implement a comprehensive, long-term Australian Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Plan.

While 58% of Australians think ‘Australia should be a leader in finding solutions on climate change’ there are significant political roadblocks preventing the rapid implementation of post-carbon economy transition strategies. Actions required include the following:

- Overcoming climate science denial and deepening understanding

of the necessity and urgency of action

- Overcoming the power and influence of the fossil fuel industry and its allies

- Overcoming political paralysis and strengthening the determination of communities, governments and businesses to take decisive action

- Developing an economic paradigm focused on wellbeing and resilience rather than unsustainable consumption of energy and resources

- Overcoming technological and social path dependencies and driving social, economic and technological innovation

- Strengthening the financial and governance capabilities needed

to drive swift implementation of large-scale de-carbonisation.

Not much if you say it quickly. Now here’s the rub. Wiseman says:

- Courageous moral leadership – at multiple levels and in many sectors – is an essential precondition for rapid implementation of post carbon economy transition strategies.

And we need a redefinition of prosperity.

So do we just hang around waiting for such leadership to appear? Wiseman ends with some wisdom from Milton Friedman:

- ‘Only a crisis—actual or perceived—produces real change. When the crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.’

Yes, but it seems to me that through activism we can change perceptions so that the crisis is recognised.

Here’s the deal. I’ll keep blogging and you go join at least one of those groups Ben Eltham was talking about, even if it’s just the email list of Getup!, or a political party, or both.

Climate Clippings 87, out tomorrow, has a fair bit of stuff on activism, including some more groups not mentioned by Eltham.

Update – Key climate posts by Brian:

Climate change: reconnecting politics with reality

A choice of catastrophes: the IPCC budget approach

Adding to the muddle? The IPCC climate change mitigation report

IEA and the energy crunch of 2017

I think you’d have more luck getting the current prime minister to agree to an emergency transition to a pre-carbon economy. I’m sure he’d love the “emergency” part, and phrased as a “rapid return to the traditional australian way of life” he’d be right there.

As long as no-one explained that “traditional” is being used in the sense of “traditional owners” not “traditions of the church”.

Thanks Brian. I think Wiseman (like many others including Garnaut) underestimates the role of community. Community action is certainly not just about resilience and adaptation, there is a lot being done on mitigation and sustainability at community level.

You can see some results from my project at http://fairgreenplanet.blogspot.com.au/2013/10/project-update-projects-addressing.html

There are 22 community projects there with some focus on both social justice and environmental sustainability, and this is not all – there are more projects that I have yet to enter. This is from three Victorian Primary Care Partnerships (covering a total of nine local government areas) only.

Also I keep finding out more about local climate action, including from Climate Action Networks and other groups.

A particular current interest is community solar, I plan to write something about that on the blog soon. It’s a great idea, although struggling with bureaucracy at present.

The community forum I went to the other day was about building progressive alliances. It’s difficult because there is animosity between Labor and Greens but it needs to be done.

Certainly there are also many community groups as you mention (in Victoria I’m thinking of joining Environment Victoria in addition to the other groups I belong to).

There was a staggering turnout at the Climate Action rally in Melbourne Sunday before last. I hope that counts for something when politicians are trying to claim nobody wants to address climate change.

The latest Nielsen poll is showing 57% want the carbon tax removed, but only 12% want it replaced by direction action. Seems like a recipe for no action at all to me.

Communities certainly have the capability. With governments not acting it will be interesting to see if protest action translates to significant practical community effort instead. Or if most people just give up.

Chris

Well yes. The carbon tax is seen as a resident ‘evil’. Even worse, the ALP allowed their program to be called a carbon tax, so it had something to do with Rudd v Gillard, Craig thomson, Peter Slippper, the AWU and what else do we need?

People know that DA won’t work, whatever it is, so that’s out.

The only thing people agree on is that there is no viable plan.

Interestingly, if the carbon “tax” is not repealed and a target can’t be agreed, the legislation as written ensures a 15% target.

Chris @ 4

My research is mainly in the health and community sector – includes mainly health and community agencies plus some community groups.

There’s a lot of good people working at that level, but by the same token there are problems – because the issue has been politicised some are scared to promote it (don’t want their heads above the parapet as someone put it). So I think it demonstrates how lack of political leadership at state and federal level can stifle or dampen down community action.

As Brian suggests, community groups may be an effective place to start (though even there some of them get funding from government and may therefore be cautious).

I really want to see the health sector get more involved in advocacy because health has a really powerful voice and is trusted but so far it is mainly concentrated in a few people organisations I think – like Climate and Health Alliance (which I’m a member of) and some high profile people like Peter Doherty that I have seen making statements on twitter, but need to get more of a critical mass I think.

I think one of the big questions, when you are trying to get these more mainstream organisations involved, is what is the best way to advocate? I know that I am not always good at it (sometimes I think I get so caught up in my cause that I can put people off!), so I think suggestions and ideas here would be good.

apologies for all the grammatical lapses in the above comment!

This is a classic case of a problem people can’t and won’t respond to individually. We need collective action, and that collective action requires reforming industrial practice. Everytime I hear the word “community,” I reach for my gun …

Mind you the Neilsen poll also suggests that voters are experiencing buyer’s remorse about the government they elected to axe the tax…

Brian, I think that when you said:

“First, a 50% reduction target by 2010.”

you may have meant:

“First, a 50% reduction target by 2030.”

although a 50% reduction target by 2010 would be a much more preferable option if retrospective action was possible…

Val at #2, I am convinced now that action can only come first from the grass-roots, but alas I doubt that even a strong movement at the community level will by itself have a sufficient impact to make a substantive difference. The only hope is that such community action is sufficiently widespread that it causes a fundamental shift in attitude across the majority of societies, and that this shift moves to business boardrooms and to government backrooms.

It’s a matter of numbers, and Wiseman’s chapter is worth reading because he summarises some very important ones. Of particular relevance is the comparison of 2°C world compared with a 4°C one, as described by John Schellnhuber in 2011 – no amount of citizen action alone is going to keep the realised warming to the lower end rather than the higher end…

Despite what I said above this poll:

https://twitter.com/Mad_As_Mel/status/404796144749801472/photo/1

suggests 85% want either a carbon “tax” (30%) or an ETS … (55%) … so there you go.

A further 4% want Direct Action and 11% favour scrap the “tax” and replace it with nothing.

Well its probably a bit like the polls in the US where a majority of people are opposed to Obamacare, but support the affordable care act.

Collective action can start at the neighbourhood level though. Certainly at the council level it can make quite a difference. I think its pretty clear that not much is going to happen at the federal government level for at least the next 3-6 years.

That one is just an online poll so beware But say the the carbon tax was removed by the Abbott government – do you think the ALP or Greens would support direct action policies because it would be better than nothing at all? I doubt it, which is why I think we’re at risk of ending up with no action at all at the federal level.

But say the the carbon tax was removed by the Abbott government – do you think the ALP or Greens would support direct action policies because it would be better than nothing at all? I doubt it, which is why I think we’re at risk of ending up with no action at all at the federal level.

UCLA on 5 November released a plan “to turn Los Angeles into a global model of urban sustainability”with specific objectives including:

The realization of a urban sustainability program is worth thinking about and acting on. It would disconnect households from the coal-fired power grid. It sets up a virtuous feedback, including transferable technology and skills.

Thanks for this Brian; I haven’t read the whole of Eltham’s piece, but will. On initial response I’m in Eltham’s camp on the matter of the ecological crisis and am less than sanguine about the ruling class’s willingness to let go the sources of their wealth and authority. Hence, we ought to be planning to meliorate future ecological conditions for future humans. In so far as mass action is capable of slowing the process of ecological collapse then it is worth the effort in order to play for time but imminent crisis will provoke change whereas at the moment too many people are simply too terrified to look at the issue rationally. Otherwise, my understanding of this crisis is that the globe is gripped by the delusions of a psychotic ruling class of which class the human race and the planet have no further need.

Moreover, I found the following two action points too opaque by half:

Overcoming? Aye, there’s the rub. And then there’s mention of a paradigm. I thought they were extinct.

Good turnout in Canberra. Not as big as the 2011 Say Yes to Carbon Price where we filled the Commonwealth bridge as we walked to New Parl House (and it was colder then too) – but way bigger than the 2 anti-science ones outside parl house (I made a point of driving around the APH at the time).

Love your posts on this Brian – thanks.

A very upbeat article from Newsscientist in that 2012 looked to have broken the coupling of GDP growth and emissions growth. Little, but hopefully much more to come. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22029422.800-first-sign-that-humanity-is-slowing-its-carbon-surge.html?page=1#.UpLngdJkPoc

After which time it will be too late for any truly effective action that doesn’t involve immediate and profound restructuring of Australian society.

Probably not, because Abbott’s “direct action” is actually direct inaction (the Coalition are such fans of Newspeak…) that will have no perceptible effect on emissions and indeed will siphon funds away from strategies that would have a positive effect. I’m not sure about Labor* but the Greens will not be on the wrong side of history in this.

[*I have to say that in the (admittedly brief) time since the election I’ve been underwhelmed by Shorten’s performance, but Albo, Plibersek, Evans, Wong, Marles and a few others have held up the flag for social, political, economic and environmental responsibility.]

chris

I’m sceptical. I doubt Abbott will be there in 18 months. There will either be a split or a new election and probably the return of a regime committed to pricing emissions. This regime is plainly incompetent and even the Murdochracy and the ALP can’t prop it up indefinitely.

I suppose it would depend on what the ‘direct action’ entailed and whether the regime was on its last legs and about to keel over and die of shame. At the moment, it’s just a slogan with a notional budget that sounds radically inadequate event to the pathetic 5% they are talking about.

Usage Note: “carbon tax” in an Australian context is a right wing slogan implying opposition to carbon pricing and the alienation of the commons and bearing no relevance to actual levies or taxes. It should not be used here without figurative tongs, unless of course, someone actually proposes a carbon tax policy.

Emission trading’s automatic 15%

.

That’s a keeper.

See you around Easter 2015 to review that prediction.

Did you use computer models, consensus of experts in the field or just plain old “gut instinct*”

(Not insinuating “womens intuition” for fear of a misogyny rant, Gillard style)

If we are serious about 100% renewable power we need a process that gets the right technology in the right location with the right connections. Once the percentage of renewables becomes significant we also need a system that controls the overall power system so that the use of power storage takes account of weather forecasts and local demand.

We are not going to drive these types of changes with an ETS or carbon price. Apart from the problem of the unecessary price increases driven by these systems, they do not provide the necessary controls required to get the right things in the right place at the right time What is needed is something like the Snowy River Authority to drive this major project. An authority that uses the large project management tools that are the bread and butter of the construction industry. If you like, what is needed is direct action on steroids, not Abbott’s Clayton direct action plan or the carbon price.

It would also help if we changed the way we use power so that we can take advantage of the variation in the output of renewable power. (The variable costs of producing renewable power are much much lower than they are for fossil power so there will be times when free surplus power will be available.) We need smarts, not a carbon price here.

It’s not any more convincing the umpteenth time around, John D.

I’d settle for a scheme for %100 renewables by 2015 with an opt in.

Let the people affected decide.

That’s democracy and market driven.

So who among us is already %100 renewable?

( or is that a rude question ?)

Tim: You really need to have a proper look at the BZE Stationary Energy Plan and ask yourself how you could make this happen by fiddling around with the carbon price.

I have some problems with

Firstly, there are alternatives to full electrification of people and freight transport. For example if we have clean electricity we can use existing technologies to make a range of renewable transportable fuels that could be used in the current transport fleet with only minor modifications. These fuels are unlikely to compete with direct use of electricity for urban use and high volume transport over longer distances. However, they provide a practical alternative for air and sea travel as well as low volume, long distance surface travel. (The same processes are a potential starting point for the clean-up of the petro-chemical, metallurgical and fertilizer industries.)

Secondly, there is a limit to which it makes sense to move transport from road to rail. Rail makes sense for places with high population densities like Seoul and for some types of long distance, high volume transport. But, for most of Aus road will remain part of any sensible transport plan.

Unless the laws of physics have changed recently solar and wind are useless for baseload . And you do not want gas or coal.

Am I correct in then assuming whole hearted LP and greens support for nuclear power?

You have ruled out all other options.

mk50

It’s the laws of language and public policy rather than physics that are germane to this hoary old piece of misdirection.

No. As people know, I have no objection in principle to nuclear, but it’s mendacious to suggest that alternative arrangements are not possible or feasible.

Choice is a good thing, as I’m sure you’ll agree.

The laws of physics prohibit the storage of power? When did that change occur? And I think its pretty simplistic to say that there is blanket opposition to gas power – especially when used to fill short term supply gaps.

It’s a couple of years old, but ten seconds with Google found this description of a solar farm providing baseload power. Apparently Mk50 operates in a different physical universe to the rest of us.

And there’s a lot of research into using the physics of our universe for “Baseload Concentrating Solar Power Generation”.

Dave @ 16, thanks.

Bernard J @ 10 what I said was:

Check it out with Wiseman @ 147 on the pdf, the first paragraph after Table 1. I think my summary conforms.

Fran @ 19, I’ve picked up that story about the ETS producing 15% reductions in the next Climate clippings, but with a different link. I think it’s the cap that does the work.

John D, Wiseman’s six key action plans look like direct action to me. I thought he covered the ground pretty well, including agriculture and forestry and also adaptation. Of course his specifics can be critiqued, as you have @ 25. Perhaps you should write to him and make a suggestion!

I forgot to mention that he does also see a role for an ETS, so it’s both… and for him. Garnaut didn’t see emissions trading as sufficient by itself. Relying on it is the lazy way.

I just looked at the Senate numbers and got further depressed about the prospects for emissions reduction legislation in Australia, even if the Coalition loses the next election.

Counting Xenophon as a moderate, the left-moderates won 17 Senate seats from 40 at the September election. If the WA revote results in another 4:2 right-left split, that means the left-moderates will need to win 24 seats at the 2016 election for there to be a left-moderate majority in the Senate after July 2017.

That means the left-moderates would effectively need to win 3 in 2 states and 4 in 4 states (unless the Greens win the second ACT seat in which case they “only” need 4 in 3 states – demonstrating that there may be some upside for the left in massive Coalition public service cuts). It also seems likely that the voting system will be changed before then so there may not be the same chance to fluke a 4:2 left-right split as almost happened in Tasmania this time.

24 seats is a huge hill to climb. It would represent the left’s greatest Senate triumph since Chifley introduced proportional representation. Barring a successful double dissolution, which probably couldn’t occur earlier than mid 2017 and possibly early 2018, the right will very likely hold the Senate until July 2020. And of course, 2020 is when we should be hitting our first emissions reduction target, whatever it is.

I suppose a shorter way of saying the above is that Labor needs to win 2 elections at least if it wants to pass carbon pricing legislation without conservative defections. Either two ordinary elections in 2016 and 2019, passing the legislation after July 2020, or an ordinary election in 2016 and a double dissolution in 2017 or 2018.

Compass: Well said. Sounds like Labor is unlikely to be able to do anything with the carbon price before 2020. Which means that, if Labor persists with the carbon price it will have spent 13 long years on the carbon price with almost nothing to show for it. The reality is that the carbon price has become nothing more than a “great big distraction” that diverts attention from effective climate action.

Before the climate price tragics start screaming it is worth remembering some of the things that have worked over the years:

Turnbull’s efficient lighting regulations

Howard’s RET emission trading scheme – one of the few emission trading schemes in the world that is actually working.

The various FIT schemes. (Would be better if market forces were used to set contract FIT’s.

The home insulation scheme.

It also looks like the ACT solar auction scheme is starting to work.

John D, it seems to me that the only “carbon price tragic” on this blog is you.

It’s you continues to insist, with tiresome repetition, that, for reasons only known to yourself, a carbon price is the only unacceptable policy tool to address climate change, and quixotically redefines terms like “market-based mechanism” and “emissions trading scheme” to suit your increasingly strained arguments. Nobody else here that I’m aware of (excluding the periodic denialist trolls) objects to any of the other policy measures you’ve listed.

Your apparent belief, in a political climate where even the modest (and according to the Climate Institute, quite effective) carbon price is unacceptable, and the RET and all other renewable energy policies are under threat, that enthusiasm for much more ambitious climate action would magically revive if only we stopped talking about that pesky carbon price, seems to me to be bordering on the delusional.

The problem isn’t the carbon price – the problem is that half of our political establishment has decided that addressing climate change is not something they want to bother with.

I can’t improve on that Tim.

I’m all for a mix of policy approaches, as I’ve repeatedly made clear, but as you say, the underlying constraint is not the method but the goal — decarbonisation.

John D, I wasn’t suggesting Labor, or anyone, abandon carbon pricing.

Brian at #31.

I see your point now. My bad – I didn’t read that far into the chapter before I posted and assumed that you had worked from the graph.

Apologies.

I’m truly puzzled to the ongoing opposition to a carbon price.

In a fair society a polluter or other damager of the commons is usually required (or at least expected) to pay for the real cost of their damage. We do it for particulate pollution, and water pollution, and ozone-destroying pollution, and littering, and so on. And yet in the case of fossil fuels not only does the emitter not have to pay for the carbon dioxide damage, but the taxpayer subsidises this staggeringly profitable industry until they bleed!

Any conservative (and capitalist) democrat should be screaming for a carbon price, and yet they bray in entirely the opposite direction. In Australia the added irony is that these same people to a large extent support the (socialist) approach of direct action which, in the Coalition’s current guise, is no better than pissing on a bushfire.

If these conservatives are afraid of the carbon pricing now they should wait for another decade or so – by then real direct action will be looming, if not already enacted, and it will make them bleed harder than they could imagine now in their worst nightmares. And if said conservatives are patient, in good health, and younger than about 50, they will live to see economica dn environmental consequential costs that will make them rue their resistance to a modest carbon price such as we currently have.

And to concur with Tim and Fran, the solution will be an integrated approach involving more than just a particular policy respond to one aspect of energy provision, but that’s the topic for a separate thread.

Gemasolar project (http://theenergycollective.com/nathan-wilson/58791/20mw-gemasolar-plant-elegant-pricey) –

Now, that’s a construction cost of US$20.95/W. Construction costs for new nuclear plants in the US are US$3.50/W, JapanUS$2.00/W, China claims US$1.30 to US$1.50/W. (re: http://nuclearinfo.net/Nuclearpower/WebHomeCostOfNuclearPower). US nuclear generation costs are just $0.0168/KWHr. The Thai Binh II 1200MW coal fired plant in Vietnam is building now and will go live in 2015 (one of over 1,000 coal fired stations under construction globally) at a cost of US$830m, or US$1.45/w construction cost. Solar not-quite-baseload – $20.95/W to build and not scalable, coal $1.45/W to build and scalable. Good luck with solar, Don Carlos…

http://theenergycollective.com/lindsay-wilson/279126/average-electricity-prices-around-world-kwh – Decent article on relative electricity prices globally

http://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherhelman/2012/12/21/why-its-the-end-of-the-line-for-wind-power/ – Decent article on the actual cost of wind power and how it cannot compete without subsidy

In 2008-09 Australian electricity was produced from 56 gigawatts (GWe) capacity, of which 30.3 GWe (54%) was coal-fired, 14.7 GWe (26%) gas or multi-fuel, 1.35 (2.4%) oil, 7.1 GWe (13%) hydro and 2.5 GWe (4.5%) other renewables. This cannot be replaced by wind or solar as it would cost US$1,156 billion using the Gemasolar construction cost (vs US$112 Bn using Japanese nuclear costs, US$81 Bn using Thai Bin costs). On electricity storage, no technology exists for storing electricity at baseload demand level:

(The Cost of Generating Electricity: A study carried out by PB Power for The Royal Academy of Engineering ISBN 1-903496-11-X, March 2004, Published by The Royal Academy of Engineering, 29 Great Peter Street, Westminster, London, SW1P 3LW p.12.). Hence my comment about the laws of physics. Sure there’s research as Zoot notes, but research is not functioning commercially viable technology – storing baseload levels of electricity required cheap room temperature superconductors somehow worked into titanic capacitors and with some mechanism to bleed off high tension loads – all three technologies are science fiction right now. So if you oppose conventional thermal on actual environmental grounds you must embrace nuclear. There’s no other option unless being irreal or simple μῖσος ἄνθρωπος are considered options. The physics gives us the simple, verifiable fact is that baseload civilisations such as ours cannot be run from irregular, low efficiency dispersed energy systems.

So the promising technologies don’t store electricity. The laws of physics do not mitigate against renewable supply of baseload electricity.

Zoot:

No, they do not. A 90%+ efficient, rugged, cheap, long-life solar energy converter to provide power from remote desert locations, and cheap room temperature superconductors to transmit the electricity to cities are not ruled out by current knowledge of physics. But again, at this time, both technologies are science fiction.

Nuclear is logically and philosophically unavoidable IF one still adheres to the concept that CO2 is some form of global temperature rheostat. it is arguable that holding to that belief and rejecting nuclear power is prima facie evidence of a fundamental lack of seriousness. And commercially viable fusion appears to endlessly be as far away as commercially viable baseload solar and wind. Certainly, the figures above show how unviable these are. This is typical of immature technologies.

Another blow against the wind farm deniers:

http://yes2renewables.org/2013/11/26/vcat-approves-the-cherry-tree-range-wind-farm/

Compass: As you say @38 it is unlikely that Labor could reimpose a carbon tax or ETS before July 2020 at the earliest. Even if they did impose a carbon price high enough to drive real change in 2020 it would take time for the renewable power generators etc to be built.

Maybe I am missing something but my reading of your statements is that talking about the carbon price will be nothing but a distraction for at least the next 8 years. A distraction that Abbott will use to cover up for the inadequacies of his direct action plan.

This is why I think that the best thing that Labor or the Greens could do right now for climate action is abstain from the carbon tax vote and get on with talking about alternatives.

Practical alternatives include things like individuals, communities local government etc. acting to reduce their emissions. Lots can be done without depending on the co-operation of the federal government.

Practical alternatives can also include arguing for improvements to the governments direct action plan or couching proposals in ways that take advantage of LNP mindsets.

I can’t see Abbott wanting to talk about alternatives to the carbon price without leverage and it seems to me that abstaining from the vote would throw away that leverage.

Labour and the Greens have the opinion polls behind them to move to effective action post-Carbon ‘tax’ so they should use what power they have to ensure all direct action is effective at the least but also to move to an ETS if possible.

Tim @36: Is the RET a market based system?

Yep: The price of credits/permits is determined by a trading market.

Is the RET a defacto emissions trading scheme?

Yep: It is a simplified system that treats all renewables as equally clean and all non-renewables as equally dirty. It could easily be based on actual emissions but this makes the measurements more complex and encourages the use of the gas transition. (It is too late for the gas transition.)

Is the RET a tax?

Nope: It generates no government revenue.

Are there similar offset trading schemes being used elsewhere?

The US acid rain trading system is another successful scheme that does not generate government revenue.

Can RET type schemes be applied to other sources of emissions?

Yep: An RET style system is a logical choice for driving down the average emissions of new cars Offset credit trading is particularly suited for situations where the aim is to control an average and where there is no shortage of better than target product.

Are schemes like the ACT solar auction scheme market based?

Yep: Any system that uses competitive tendering or auctions to set up long term contracts are classical market based systems that help minimize prices.

Of course the RET is a market-based mechanism, John D. When did I suggest otherwise? While we’re on the subject of the RET, I have couple of other questions for you – how is the RET determined? Is it subject to political interference? Has it caused periodic turmoil and disturbance in the renewable electricity industry? Is this desirable? How could it be improved?

Mk50 @ 41 and elsewhere

“The physics gives us the simple, verifiable fact is that baseload civilisations such as ours cannot be run from irregular, low efficiency dispersed energy systems.”

I have previously been mainly irritated by advocates of nuclear, seeing them (particularly in the Australian context) as at the least a diversion that weakens to overall movement for alternatives to fossil fuels, and at worst, front people for climate change denial. However looking at your comments, you appear both knowledgeable and sincere.

So giving you credit for this, I want to try out on you a line of argument I am currently working on, and I hope you will respond to it. It may not make a lot of sense yet, but hopefully this process of putting it out there might help with that.

Your comment that I have quoted above – about what “baseload civilisations such as ours” require – is particularly interesting because of the assumptions buried in it, which I would like to analyse. In some ways it is reminiscent of, though much more sophisticated than, the crude comments one sees on the internet about the crazy deep greens want to take us back to the stone age etc.

So the question is, ,do you think that we live the way we do in wealthy societies such as Australia because it is a genuinely good way to live? or because even if it’s not ‘good’, it’s the way we want to live? or because it’s not good but we are incapable of changing? or because ‘other people/the majority’ are wedded to this way of life, and (even if you yourself were capable of living in a way that did not need these levels of baseline power) cannot/will not change?

I will cut this off a bit now because it’s so long, but the point I’m working towards is – briefly – that from a public health perspective our way of living has reached a tipping point where it is actually harming our health – particularly in regard to obesity – and we would be better off without these levels of baseline power.

Tim there was a period of destabilization when rooftop solar was included in the scheme. Periods of destabilization are inevitable with trading systems like the RET and proposed ETS. Particularly so when it takes time for new capacity to be built. (This timing problem would there for using an RET style scheme for driving down the fuel consumption of new cars.)

In the case of the RET some of the uncertainity has been removed because the actual target is not % renewables but gWh/year renewables. The fossil power producers don’t like it because they have to wear most of the uncertainity.

The other problem with the RET is that both Rudd and Abbott have demonstrated that it is easy for politicians to create uncertainity by changing targets.

In terms of driving investment in renewable power my preference is to use some form competive tendering/auction to set up long term contracts for the supply of renewable power capacity. Long term contracts provide investor certainity and encourage very competitve bids. Competive tendering pushes down prices.

In the longer term, contract tendering systems have the added advantage of allowing location, technology etc to be specified.

An RET system for new cars does not require any change in the price of fuel to work. It raises the price of gas guzzlers and reduces the price of low emission cars. There is no reason why it could not be extended to encourage retrofits to older cars.

Val, you give MK50 way too much credit.

MK50 said “And commercially viable fusion appears to endlessly be as far away as commercially viable baseload solar and wind. ”

MK50 thinks baseload is a power source when it is a power demand.

http://www.global-greenhouse-warming.com/myth-of-baseload.html

Salient Green @ 51

Thanks for that, it was interesting. I’ve read several reports from reputable sources that say we can get to 100% renewable within a few decades, so I don’t actually believe Mk50 is right. I also believe that some people advocating nuclear are actually front people for a broader corporate lobby that fundamentally just wants to protect the rights of big corporations to make profits from energy generation. However there are some commentators on this blog who seem to me to be genuine in their advocacy for nuclear.

So as well as the technical discussion – which is not my area of expertise – I’m also interested in the social discussion: why do they think we, as a society, require this particular amount of generated power, available at all times (which seems to be the basis of their arguments)? What do they think would happen to us, as a society, if we didn’t have this?

I think for people who are interested in technical discussions, it may be quite difficult to recognise or explicate their basic assumptions (and values) about society, but I think it is a very important discussion to have.

Labor has a strong tactical interest in biding its time on this issue. On the basis of past experience, it can be sure that any policy proposal it puts forward will be denounced by the Greens as not going far enough, which they also know the Greens are prepared to back up this threat by voting down any legislation they put forward and aligning with the Coalition.

So Labor is best to go to the next Federal election with a minimalist platform on carbon change policies, and see which way the Greens vote goes. If it goes up, there is clearly public demand for strong action in this area. If it goes down, Labor may be better served to focus its attention at the 2019 poll (or whenever a second Federal election after 2013 is held) on its more traditional areas of policy strength such as education, health and public services.

Personally, I would like to see Labor leaders putting nuclear power on the agenda, but I see that as very unlikely to happen for reasons of basic electoral arithmetic.

Terry @ 53

So Terry why do you think we need nuclear power? What are the essential social needs that justify nuclear, rather than renewables?

I am unconvinced that renewables can take up the load currently generated by coal. Also, I think that if you massively ramped up the number of wind farms in Australia, the level of complaint about them would grow considerably. It is worth noting that Bob brown called for a moratorium on the construction of wind farms in Tasmania due to their adverse impact on the wedge tailed eagle population.

My thinking is guided in part by how China is responding to its pressing need to reduce CO2 emissions from coal-fired power stations. They are building 24 new nuclear power plants. Significantly, they rejected wind power as taking up too much available space. The British decision to go ahead with the Hinkley Point reactor, having pursued wind as an alternative for so long, is also significant in shaping my thinking.

One can point to Fukushima in Japan. But one can also point to France, which is mostly nuclear powered, has some of the cheapest and most abundant energy in Europe, and is a relatively low CO2 emitter.

Finally, Australia is one of the world’s major producers and exporters of uranium, which fuels other nations’ nuclear reactors, so the opposition to nuclear power plants in Australia is philosophically inconsistent.

I would have thought it was best for Labor to try to win the next Federal election. The last three times Labor deposed an incumbent Federal Coalition government, it had clearly superior policies on salient environmental issues.

Also, for various reasons the Greens vote is not necessarily a reliable indicator of public demand for action on environmental issues. I doubt that the public demand for environmental action among the electors of the seat of Sydney is less than half of what it is among the electors of the seat of Melbourne.

I don’t think its necessary, but the alternatives are generally not cheap or easy. I think if it wasn’t available that inevitably rationing would occur based on price rather than need. So we’d end up with the poorer sections of society going without heating/cooling which they can currently access. The same people who are the least able to afford (or be allowed) to improve the places they live in to be more energy efficient.

The rich would be fine – they can either buy from the grid at higher prices or invest in wind/solar with storage capabilities. The middle class would experience a decrease in living standards and probably vote a new government in that gave them access to cheap energy again.

Val, I have a comment in moderation that answers your question @ 54. Not sure why it is there, but anyway …

[Moderator note: it was bot-modded because it had more than two links]Chris @ 57

Thanks Chris that’s interesting. Hoping to get a few more responses and we can compare what people think about this.

So just to repeat the question for anyone who believes we will (or may) need to build nuclear capacity rather than going for 100% renewables: what is the social* need that justifies this, in your view?

(*not the technical reasons)

What Chris describes @ 58 is exactly what is now occurring in the UK right now, as winter approaches. Ed Miliband’s pledge to freeze energy prices if elected is popular, but far more people see the pricing problem as arising from “green taxes” than the behaviour of the companies themselves.

Terry @ 58

Hi Terry thanks for your answer but it is still assuming we need the same amount of power delivered in the same way.

So to make my question a bit more specific, what do you see as the social* factors that would prevent us from reducing power usage, coping with rationing and/or using intermittent power sources, if those things were necessary on the way to 100% renewables?

*Social includes political and economic, but I am also interested in ideas about more narrowly ‘social’ factors (eg ‘way of life’).

Val: 60% of the power in the BZE Stationary Energy Planwill come from concenrtated solar tower (CST) power generation. Each CST plant will have about 17 hrs worth of molten salt energy storage with back-up molten salt heaters (in this plan the heat comes from burning bio-waste but it could come from other sources.) The back-up means that CST can provide 24/7 power.

Nuclear is not needed to achieve 100% renewables

Terry (arguing for the inclusion of nuclear power in Australia’s energy mix)

Speaking as someone who is on the record here as not opposing in principle the inclusion of nuclear power in the energy mix

I don’t believe nuclear power could in practice do that job on the timeline we need it to do that job Australia currently has about 30GW of installed coal capacity. Replacing that with nuclear power would require something like 25 nuclear reactors scattered mostly across the eastern seaboard. Even if we started tomorrow by having the majors approve the concept, this would require all manner of special legislation overriding local council objections. The matter would be tied up in the courts for some years. No developer would become involved at least until test cases had been won. If one looks at the places building nuclear power plants where there is no serious opposition, construction tiomes of 8-9 years are the norm. Apart from China, which has a quite disticintively authoritarian system, none of these is attempting to build on this scale. I believe the UAE is doing about 5GW.

To do this you’d need some serious engineering capacity which we’d have to outsource. And if every serious emitter tried to do it on this scale, source engineering capacity would become even tougher. Even the major demand for wind turbines tested constraints.

Or, you could build renewables that could be online within months. This is something that we could conceivably do here — perhaps with some of those displaced car workers.

The “complaint” is from a quite narrow group of eccentrics and matters in the courts lately have been running against them. VCAT for example has just knocked out their main objection in approving a new development.

Not really worth noting. There are no coal fired power plants in Tasmania.

Since you raise it though:

That’s one site, in 2008. It seems though that there may not be such a problem even with this one.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/ockhamsrazor/the-death-toll-of-brds-due-to-wind-farms/5040794#transcript

Keep in mind too that for nuclear power plants to be viable you are going to have to force the shutdown of coal to make space for the new plants to trade. There is no way you’re getting out of that without massive compensation for sunk cost losses. Add that to the cost of nuclear plants plus the costs of the bidding war and you get an installed cost per GW that makes renewables look very appealing. Predictions for 2014 in the cost of solar cells are $0.20 per watt. Even allowing for a capacity credit of 20% about $30bn covers the lot. You can buy a lot of storage and still be well in front of the likely cost of nuclear power.

So there’s no doubt that if we were willing to spend the money, we could entirely replace coal.

There is a bit of opposition to wind farms here, with various local groups campaigning against them, mainly on the basis that they don’t want to look at them. There is the occasional court action which can delay things too.

Wind farms causing illness seems to be a bit of a furphy. http://theconversation.com/wind-turbine-syndrome-a-classic-communicated-disease-8318

There is also the fact that constructing and starting up a nuclear power plant is itself an energy-intensive operation, and if the pre-existing power generation system is primarily coal-fired a crash construction program of such plants will cause GHG emissions to rise above BAU for some time before producing a net reduction.

Fran is right. It doesn’t matter if you’re passionately pro-nuclear, nukes can’t be up and running quickly. They cannot be an “interim” solution.

No it wouldn’t. The state governments have pretty much plenary powers to legislate and if the federal government passed complementary legislation (and under the current federal government they would, at least from July next year) then any objections would be swiftly disposed of in the courts. You can be sure that the legislation would restrict legal remedies of injunctions, would require as a preiminary point that the litigants prove sufficient interest, defined in legislation, to even bring a suit and require them to post hefty bonds against their failure in litigation. Look at Kennett’s legislation on bringing Formula 1 racing to Albert Park then scale it up.

People tend to overrate the utility of the courts as a vehicle of obstruction to a determined government that can get its legislative program passed.

I agree with the rest of Fran’s post. The ability to build nuclear power stations in Australia would face awesome supply constraints- i.e. of people who had the skills to do so.

As Australia’s population will exceed 40 million by 2060, there is a need to plan for more energy capacity to meet the needs of a growing population, regardless of whether more people put solar panels on their roofs and electric cars become a more viable option.

John et al from @ 63

I agree that nuclear power is not necessary. However I am interested in the (generally unexamined) assumption by nuclear advocates that it is necessary because there is certain amount of generated power that we as a society have to have, and that it has to be available at all times.

So in asking the pro-nuclear people on this site about the social reasons why they think it is necessary, I am not agreeing with them that it is. I believe we should transition to 100% renewable as soon as possible, but I’m interested in understanding the resistance to this, and particularly the assumptions about society that the resistance is based on.

The question could be framed more broadly I think:

for the sake of argument, if transitioning to 100% renewable meant that, for at least some time, we as a society had to reduce our use of generated power and/or it was intermittent and/or rationed, is this feasible?

And if people think it is not, what do they see as the social reasons it is not?

Val @ 70 I would be surprised if there is much public enthusiasm for brown outs or sitting around a table with candles burning, of the sort that was familiar to anyone in NSW in the late 70s/early 80s, or to current residents of Baghdad.

Terry

This poses the question the [wrong] way. I’d be surprised if there is much public enthusiasm for trains running late because a lightning strike has hit a substation or trucks getting wedged in the M5East and causing traffic chaos but people cope and we move on.

There are ways of managing demand that can overcome shoratges with a minimum of inconvenience. Water pumping can be halted, smart meters can allow for refrigerators and air conditioners to be turned off. People can elect to have only minimal power supply between 9PM and 6AM.

Moreover, in a setting where electric vehicles and their standby batteries are hooked up to the grid these can become a source of storage from which power can be drawn down.

You mention Baghdad but there the power can be off to large parts of the city during daylight hours for 10 hours per day. Clearly, we aren’t talking about brownouts but blackouts — prolonged ones, during normal working hours.

And of course one can still use gas (including biogas) as backup.

So we should not overstate the problem.

State governments typically get the blame for brownouts and blackouts. You would need to abolish state governments in order to make prolonged blackouts palatable to Australians.

oops … careless today …

This poses the question the wrong way.

[Fixed – Mod]

Actually blackouts are probably preferable to brownouts because the latter are more likely to cause damage to electrical equipment which ends up being very expensive. Its one reason that during peak power shortages in summer that the electricity companies rotate suburbs through blackouts rather than have brownouts.

I agree you can do all these sorts of things. But electorally speaking there are going to be very unpopular. eg turning off a/c systems on hot nights. Smart meter rollouts which allow for time of use charging have generally been quite unpopular because people realise just how much peak power they use.

Whilst I think your ideas may be find theoretical solutions just don’t think in practice governments are going to be able to force this kind of change – or even willing to try. Not until its too late to make a difference anyway.

Even things like energy efficiency improvements for new homes (which is a pre-requisite for a lot of changes) gets quite a lot of push back and thats a 30-50 year plan with quite low cost. Ask people building a new home whether they’d rather spend money on a stone benchtop or extra insulation and 95% of the time I bet they go for the stone benchtop.

We could return to the 3-day working week, like Ted Heath had on the 1970s.

Why would we do that Terry, when it would be utterly unnecessary?

Chris:

Have you ever heard of a surge protector and UPS?

Again though, in practice, this would be an absolute rarity. There’s nothing to prevent a renewable system from having despatchable redundancy built into the system. We have hydro, but we could use biomass (gas, bagasse etc) and of course those lithium iron (or perhpas better than that by then) batteries for hot swap just sitting there waiting to be swapped could be drawn upon too.

This might be salutary, and invite people to become a little more frugal, or try installing solar panels with a decent FiT reflecting the value of the supply. It’s also possible — it’s done in the US — to have coops lease space on the rooves of warehouses and install solar panels there, allowing even people renting apartments to have a share of the peak supply action.

I don’t suggest they force them but nor should they shield people from the actual costs of their power preferences or hide the cost of the “gold plating” being built in as a result of an opportunistic alliance between the network service crowd and the regimes.

I don’t agree it does. There has been an overall improvement in the efficiency of the household sector over the last decade and the much maligned HIP has also doubtless helped. One of its benefits was to ease the burden at peak times.

I would say that this is a good discussion to have. To the best of my knowledge, very few say that because the train service is occasionally unreliable that we whould have a parallel service to step up, or insist that parallel roads be built so that the even more regular peak hour delays are cut by 5%.

In practice, a decentralised network based on renewables may actually be more reliable than the one we have. Yes, the power sources may be intermittent, but if the energy sources are widely dispersed then something far worse has to happen to the network than the failure of a single large power station.

People also need to consider that the free lunch humanity has had at the expense of the only ecosystem in the universe is drawing to a close. If we wish to hand on the world in respectable shape to those who come after us — and honour the concept of intergenerational equity — then we are going to need to reevaluate how we consume scarce resources — like fossil fuels and effluent sinks (such as the atmosphere).

It’s pretty clear to me that people in Australia don’t fancy the idea of nuclear power. I don’t share the concern about that held by most, but as I noted, it’s probably too late now for us to deploy that solution with advantage. Really, we’d be better supporting it in some other place likely to create an even bigger mess than us (eg Japan, Canada, Brazil, India, Mexico) — and even then, it won’t be a complete and immediate solution.

What we should do here is begin in a systematic and urgent way, to retool with renewables at whatever pricepoint improves on the lifecycle cost of new coal or gas. (i.e. we should assume a CO2 cost of about $100 tCO2e which is still conservative). Within that budget, we support renewables as widely as capacity constraints allow.

You’re seriously going to expect people to UPS their whole house? I’d love to battery backup my whole house (I produce lots of surplus power) but its very expensive. Instead I just surge protect my computers and then UPS a very small subset (ADSL modem, firewall, wifi). For the rest I just rely on insurance. And note its not just computers/TVs that need protecting from brownouts, but fridges, dishwashers, washing machines etc.

Or vote in a government that doesn’t make them to do that! Actually re: FiT – I don’t think a FiT is needed anymore – solar panels are cheap enough now. But they should let people sell their power at spot market prices to the retailers, like other generators are able to do (perhaps they’d just aggregate groups of homes).

Blackouts used to be a lot more common in Adelaide in summer, but it was so politically costly the government ended up instead just investing more in infrastructure. Yes, high power bills are unpopular, but blackouts even more so as they’re seen as a government failure (even if privatised).

I don’t disagree with you that we should be making changes, but I don’t see any suggestions which are politically feasible. Most people want the problem fixed, but also want someone else to pay for it and not to have to change their own behaviour. That’s simply not going to happen.

Chris

Well people will just need to be confronted with the consequences of their choices. There is no free lunch and it was merely an illusion that there was. There’s no point hoping to live better in retirement or salting away cash so the kids can have a better life than you do if in the end you are going to hand them a ruined world. That’s irrational. Adults often criticise young people for being reckless and dissonant, but ignoring the costs of our current policy is really the same thing.

We need our politicians to be direct and not sugarcoat what’s happening. We can avert disaster, but we are going to have to make some adjustments to our ecoservice expectations, if we want those services to be available in the same quality and quantity in 25-30 years’ time. Moreover, a change now means that in the long run, the real cost of energy will decline and we will also have cleaner air and water as a legacy. What’s not to like about that?

There is no reason why 100% renewables is going to lead to blackouts. The key thing here is to do what the BZE plan does and provide adequate energy storage and backup. As Fran suggests there are lots of temporary things that can be done to reduce the impact of shortages.

It is also worth noting that large baseload power generation actually increases the risk of blackouts. This is because a 500mW set dropping out causes much larger surges than a smaller generator of the sort used in renewable power systems.

Chris, if you’re referring to the SA/Vic interconnector for solving SA’s blackout problems then I think it would have been built and upgraded anyway for reasons of competition and efficiency.

SA exports power when the wind is blowing well. Interconnectors are vital to making 100% renewables work.

Val:

Happy to discuss when I return from work. For whoever above, I use ‘baseload civilisation’ as a shorthand to describe a civilisation such as we have, one existentially dependent on reliable and cheap supplies of electricity.

A place to start this conversation is to first state ones assumptions. Are you willing/able to do that?

Mk50 @ 84

Well my key assumptions relevant to this discussion are:

– A shift to 100% renewable energy in several decades is possible, but there considerable vested interests opposing this

-A reduction in generated energy use (and an increase in human energy expenditure) would have considerable benefits for health in wealthy societies as well as reducing carbon emissions

Val:

Your drived assumptions appear to be

– belief that anthropogenic global warming exists

– belief that AGW is the primary cause of global warming

– belief that CO2 is the primary cause of global warming

Val:

See next post

Derived assumptions from this appear to be:

– our form of technological civilisation (‘baseload civilisation’) is of questionable value

– there are/may be better forms of civilisation than this at lower technology levels

Is this a fair assessment of your assumptions? If so, I am quite happy to list mine.

Mk50 @ 87

I think you may be going off on a tangent here – it’s actually energy I’m talking about, not technology (btw ‘lower technology levels’ is not clear – does it mean less technology, or less smart technology?)

Eg – a lot of car trips in cities could be replaced with walking or cycling, in combination with public transport. PT can be technologically sophisticated – it’s not the technological sophistication that’s the issue, it’s the use of energy. In societies like ours, the majority of people would benefit from doing more physical activity (direct human energy expenditure), while PT and cars both use energy generated from other sources (at present mainly from fossil fuels) but PT uses it more efficiently.

OK. Use of energy, with the assumptions listed generally agreed to but seen as tangential in many cases.

My own most fundamental assumptions are that:

– western technological civilisation is superior to all others and within that the subset of Anglo values are superior

– the post-1880 social and legal values of western civilisation are superior to all others with the additional sub-caveat above

– since 1820 western civilisation combined with the capitalist values of the 1st and 2nd globalisations have reduced global poverty levels* both in absolute and relative terms

My argument will generally accord to the line that expanding energy use while simultaneously improving energy efficiency (ie: reducing energy useage per unit of output) at the global level is essential to decreasing human poverty and raising living standards at the global level.

This is an argument that categorically rejects the AGW thesis. The reason I raised that point is that it’s an emotive issue, and can cause interlocutors to veer into emotive argument not based on rational matters. As the argument is based on energy efficiency it is inherently based on costs. Hence my comments above that ‘we should use thermal coal generation for baseload in Australia as it provides the cheapest source of electricity.’

* As defined by Surjit S. Bhalla, Imagine There’s No Country: Poverty, Inequality, and Growth in the Era of Globalization, Institute for International Economics, Washington, 2002, Ch.6.

Mk50 what is it that happened in 1880 or thereabouts which changed the social and legal values of western civilisation so as to make it superior to all others?

While you are about it this has got me wondering:

I can accept the argument about poverty being reduced in relative terms but I wonder how that can be true in absolute terms.

In 1820 the world’s population was less than one billion. In 2013 it is about seven billion. Of that seven billion at least one billion live in absolute poverty or, to put it another way, materially no differently than they would have in 1820 in terms of nutrition, housing, access to water and hygeine.

If only a billion people lived in 1820 with say 100 million not living in poverty, and seven billion people live today, one billion of them in poverty, can you explain how poverty has been reduced in absolute terms?

Mk50 @ 89

I originally asked the question about assumptions because I was trying to work out the social reasons why people thought Australia should adopt nuclear rather than work towards 100% renewable. You’ve moved a long way from that question, and also into the territory of values rather than assumptions.

I trained as an historian before moving into public health and your position looks frighteningly simplistic (and potentially racist) to me. I don’t have time to get into this discussion now and it’s not relevant to this post, but I suggest that you read more history. As a starting point, you could even look at one of the posts on my blog http://fairgreenplanet.blogspot.com.au/2013/11/why-we-should-acknowledge-elders-and.html. I would be prepared to discuss your assertions about western civilization in more detail there, time permitting.

Brian generally puts a statement on his climate clippings posts that they are not about debating the science of climate change and I imagine it also applies to this post. There are other blogs where you could have discussions as an AGW denier; it seems discourteous and a waste of people’s time to do so on a blog where people are specifically asked not to do that.

GregM

Re 1880 and all that: Third Reform Act 1884 I would think? And irresistible momentum toward universal suffrage – Adult Suffrage Act 1894 in SA, at least.

@89:

No it doesn’t. The scientific validity or otherwise of the AGW thesis is a matter of physics, chemistry and related natural sciences that is not affected by political or economic arguments. Of course if it is true this has consequences for the feasibility of human social and economic options, including some that many people believe, or have believed, to be greatly desirable. However this is not a basis on which to form a judgment about the science.

That I might prefer to live for 200 years rather than somewhat less than 100 is not a reason for me to believe that I am a giant tortoise rather than a human being.

In 1882 the first bookmakers were licensed to operate at Flemington racecourse.

Val:

Assumptions are based on values. What I am trying to do is to engage on a basis of knowledge so as to avoid what normally happens: the non-left-oriented person discusses facts on a basis of their assumptions and values; this triggers and emotive response on the part of the left-oriented person and at best the two start talking past each other. I am simply not interested in discussing AGW with anyone here – there is no point in holding a religious discussion and it’s discourteous.

Note your own emotive response above. Also note that the only source I have quoted so far is by Surjit Bhalla. He and Deepak Lal are by far the most accessible of economists on the subjects of poverty eradication and lowering of inequality. The Indians are more advanced than anyone in these spheres for obvious reasons (everyone uses their 1961 economic modelling of poverty), and are part of the ‘Anglosphere’, having developed a means to turn their economy into an ‘Anglo’ economy while not so altering their culture.

And India is the country which actually illustrates the point you raise. They have actually chosen to reject the thesis on which the European move to renewables was based (in policy terms) and to adopt nuclear and coal while rejecting renewables completely. Indeed, they are moving to installation of thorium reactors. They have already held this social discussion and moved from it into national policy.

I note your point on being history trained. That’s good. I am a published historian and that’s what my PhD is in.

@96

Sorry, but it’s not worth trying to argue with anyone who says that accepting the science of AGW is akin to a religion, and tries to undermine people who do accept it by calling them “emotive”.

Depressing that someone could have a PhD in history and still do this.

And in 1883 Marx died.

It’s an example of the “two cultures” on steroids.

On the other hand, the sort of strong social constructivism that Mark brings to questions of climate science does have its adherents in the discipline of history.

Val:

It is interesting that your rejection of your own desire of “…trying to work out the social reasons why people thought Australia should adopt nuclear rather than work towards 100% renewable” is actually based on an emotive response. Note that I have used the term ’emotive response’. It’s a very human thing to have these: rational people do too, and we note them, adjust our thinking and most certainly adjust what we say to remove the emotive quotient, and continue the civil discourse. Some of the most interesting discussions I have ever had have been with committed life-long marxists.

It’s interesting that you do not wish to commence a civil discourse you requested, apparently based on an emotive response to my not according with your belief system (which is why I wanted assumptions etc stated up front). The outcome is that I can accept your assumptions and values while not agreeing with them, and you are not able to accept my assumptions and values even as legitimate. This is the mark of an ideologue (and this is quite standard for people with a left-wing ideology) – you may wish to ponder the implications. If you are not able to control your emotive responses then your wish to abort the discussion is certainly better than you wasting my time in the inevitable emotive morass which can only result . It is admirable that you wish to withdraw based on a self-assessment that you consider yourself not capable of civil discourse with someone who does not share your world-view.

Finally, I would point you to the large body of scholarship, government policy and government-academic-public debate in India over the last forty years on precisely your stated topic of interest: “…trying to work out the social reasons why people thought Australia should adopt nuclear rather than work towards 100% renewable”. You will find many answers there.

Very briefly, Mk50, if it is indeed your assertion that AGW theory is “akin to a religion” then in practice, it’s hard to imagine how one could have a useful conversation with you based on reason and salient data about any topic in which an assumption that AGW theory was sound was foundational.

The word “religion” describes a set of practices and rites performed purely for the satisfaction of deities and to earn favour from them in this life or the next.

The practices of science go to the intellectual integrity of the inquiry and are modified as new and more functionally robust methods are developed. These are clearly different things.

Though not as a direct result of developments in Flemington.

Can’t have helped though.

Paul Norton @ 100

My theoretical approach is broadly constructivist. However there is a certain point, useful to corporations in many ways, where post-modernist meets high capitalism. I never go there, but it looks like Mk50 might live there.

@ 101

Debating with someone who makes specious arguments is a waste of time, but I would like to remind you that it is Brian who asks people not to debate the science of AGW on his posts.

If you wish to have an argument about that, you would need to have it with him.

Seems like Mk may be referring to the great globalisation of trade forged by the supposedly superior anglosphere, bookended by the dates he suggests.

That is the first and second opium wars, occuring between the 1830’s and 1870’s.

The begining of global ‘free trade’ and the modern industrial trading corporation.

Which also relates to the recent history of his so called anglo-India.

@ 89

“- the post-1880 social and legal values of western civilisation are superior to all others … ”

I am responding to this on overflow thread because I have just read something so horrifying that it requires someone to address this comment of yours.

And my response is emotive, as it should be.

Marx would have regarded bookmakers and much of their clientele as part of the lumpenproletariat.

At #96:

At #101:

It’s interesting that you conflate the parsimonious conclusions of the best science as conducted by thousands of the world’s professional scientists with religious belief and dismiss those conclusions on this basis, and then accuse others of emotiveness.

How do you so dismiss the science that soundly indicates the human involvement in contemporary climate change, and how do you expect to hold a conversation about any subject where the consequences of climate change are relevant if you do not confront and address the science?

Perhaps it is permissible in history academia to consider only one side of an issue, but in science objective an impartiality, logic, evidence, and a complete accounting of all relevant factors are required. Your method of pushing for a particular interpretation of facts may have some (not necessarily valid) utility in a post hoc approach to matters, but it has no predictive ability whatsoever, especially if you dismiss a priori a whole corpus of knowledge that would otherwise profoundly alter the conclusions of your assessment.

Ah, if I’d refreshed I’d have seen that Fran had said pretty much the same thing at #102…

Gentlefolk:

The Sunday evening Catalyst special program on ABC-TV1 Don’t Panic: Surviving Extremes was excellent.

Instead of taking a global approach to the problems of climate change, it simply gave good practical advice to ordinary families on how to survive two inevitable consequences of a one degree (I think it was) increase in average temperatures.

Refreshing change in approach to the problems – and one more likely to upset the climate change sceptics too.

Hi everyone sorry for inadvertently starting the derail by Mk50, I didn’t realise he was an climate change denier. (I’ve started a discussion on overflow if anyone wants to critique the imperialist privileging of “western civilization”.)

Just saw from twitter a really good article on LSE blogs that sets out some of the social issues I’m interested in – worth reading (damn it somehow have me wrong link will have to try again)

This is the link to the Nikolas Scherer article I referred to above

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/11/28/climate-change-discussions-must-move-away-from-the-green-growth-model-and-focus-more-on-political-and-social-change/

(Mods I hope this can be released before the discussion moves on? Also last time I looked I had a comment stuck in moderation on overflow for no apparent reason)